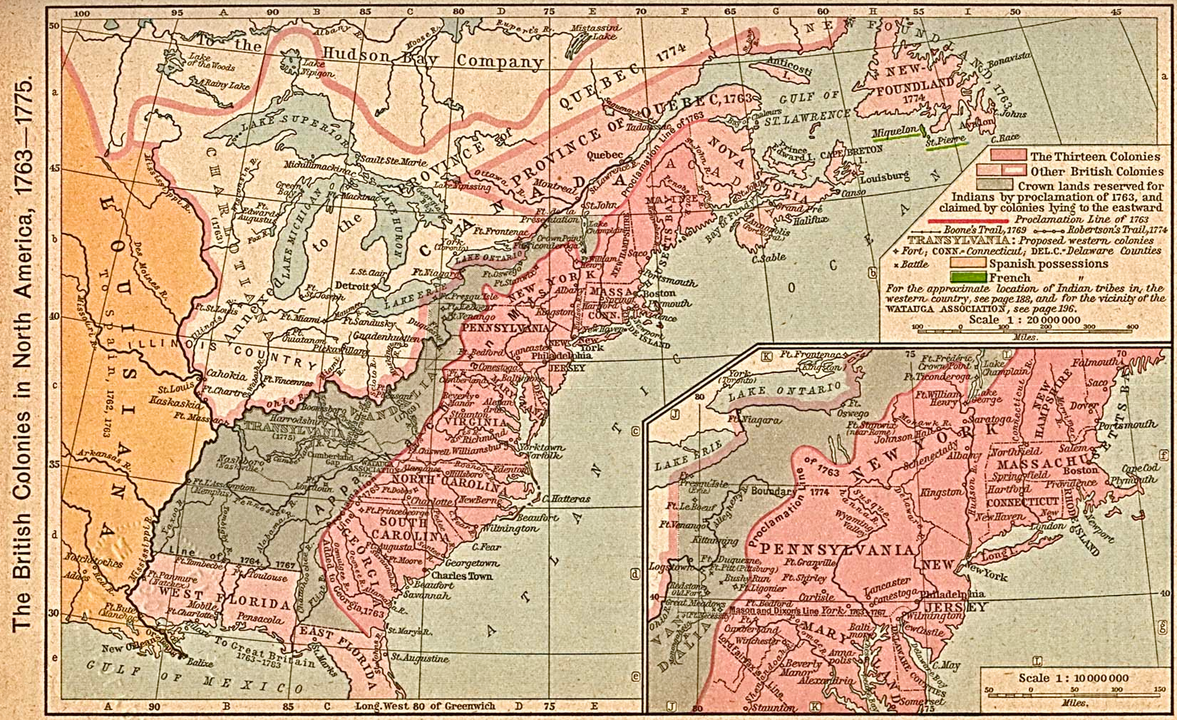

Forgotten by textbooks but founder of Chicago, Jean-Baptiste Pointe du Sable was a Black pioneer, trader, and builder whose story unsettles official narratives. This account reveals the man, the interracial couple, and the city before the city.

A man, a city, an erased memory

The wind that sweeps the shores of Lake Michigan carries the metallic scent of water and the constant rumble of the avenues. There, just a few steps from the DuSable Bridge, the skyscrapers cast long shadows on Pioneer Court, a paved square that tourists cross without paying much attention. Rarely do they glance up at the bronze bust at the entrance—its impassive face gazing fixedly toward the waters of the Chicago River.

This is where it all began.

Long before concrete, before railways, before the black gold rush of industrial capitalism, a (Black) man laid wooden foundations on the riverbank. His name: Jean-Baptiste Pointe du Sable. His story: that of a shadow pioneer, erased from official accounts, yet whose hands traced the first outlines of what would become the third-largest city in the United States. A man of sand, in both the literal and metaphorical sense: fluid, elusive, rooted in shifting ground.

Pointe du Sable was neither general nor governor nor priest. He did not conquer lands with fire, but with the patience of trade, the strength of connection, the strategy of bridges over walls. He spoke several languages, married an Indigenous woman, and negotiated between nations, surviving the turbulence of a continent still in the making. And yet, for more than a century, he was reduced to a ghost. His name erased from textbooks. His role minimized, mistaken, ignored.

Today, a plaque, a museum, a school, a bridge. But is that enough to repair a historical omission? Can we still recover the thread of this life, through conflicting accounts, archival silences, and myths reshaped in hindsight?

This essay opens like an excavation: in search of a man history failed to keep at the surface. A man who, from the sand on the shores of the Chicago River, raised a city.

The unknown with many faces

Who was Jean-Baptiste Pointe du Sable really? Before he became known as the “first permanent resident” of Chicago, even before being recognized as the “Black founder” of the city, he was (and remains) a mystery. His birth, his childhood, his education—even his native language—escape historical certainty. The story of Pointe du Sable has no clearly established origin, only hypotheses, fragments, and silences layered by the centuries.

Some traditions claim he was born in Saint-Domingue (present-day Haiti) around 1745. Other sources imagine him the son of a Frenchman and an African woman, born somewhere on the shores of Saint-Marc Island. Still others suggest he may have been born on the North American continent, perhaps in French Canada, to a Creole or mixed-race family descended from the Dandonneaus, known as “Du Sable”—a name borne by settlers around the Great Lakes. But no civil record settles the question. At his death in 1818, his burial record simply identifies him as “negro,” without mention of parentage or origin.

This biographical haze is not mere trivia—it reflects the fate of many Black figures in national histories. Their lives often begin at the moment they enter Western archives, and their pasts are left fallow. In Pointe du Sable’s case, this absence allowed for a range of conflicting stories to flourish: some saw him as a freed former slave, others as a Haitian merchant educated in France, still others as the son of a Black sailor turned pirate.

Where European pioneers benefit from complete genealogies, painted portraits, and personal journals, Pointe du Sable remains elusive. No image of him survives—only a romantic engraving created decades after his death, in which his profile is imagined. And yet this visual void has allowed for his reinvention: for Haitians, he is a hero of the diaspora; for African Americans, a forgotten founding father; for Native Americans, a son-in-law and mediator; for Chicago, a long-ignored enigma.

But perhaps this multiplicity is a strength rather than a flaw. Pointe du Sable embodies precisely what colonial borders sought to deny: the porosity of identities, the overlap of worlds, the crossing of lines. He is the archetype of the Afro-descendant frontier man: neither Indigenous nor settler, neither passive nor submissive, but an actor, builder, and strategist.

And perhaps it was this very ambiguity that made him such a dangerous figure to official history?

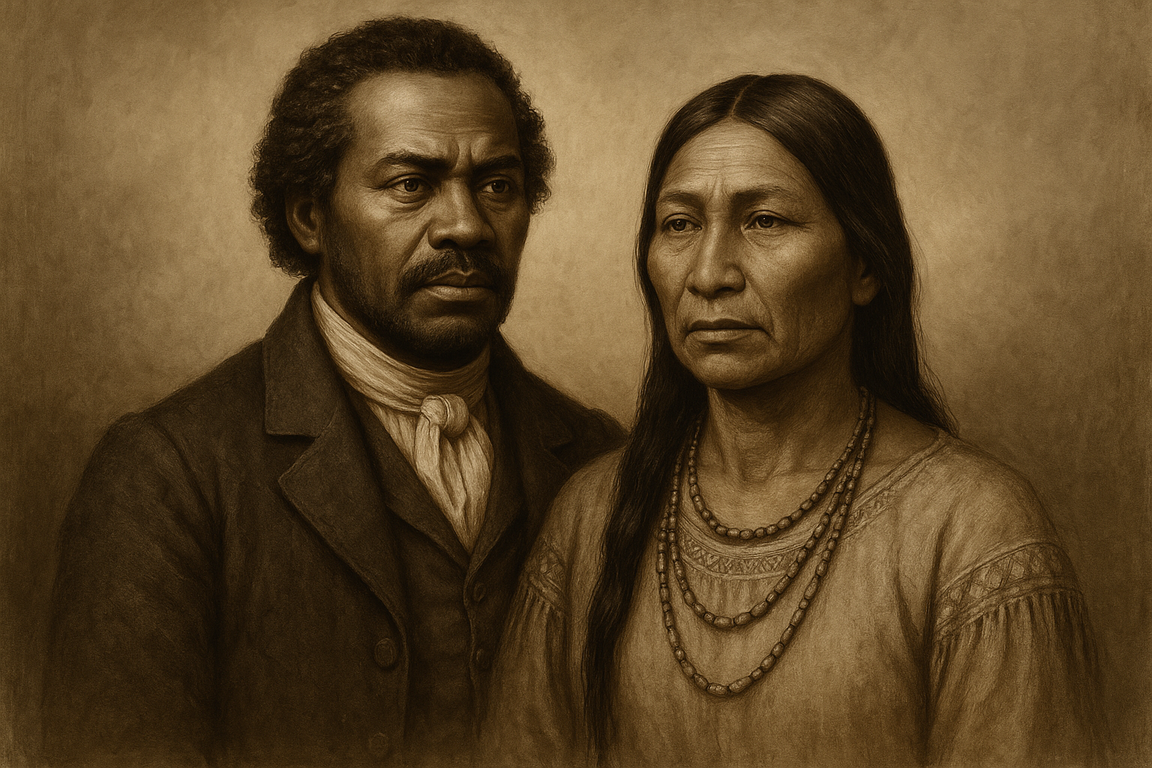

Kitihawa and the clash of worlds

Before it was a city, Chicago was a meeting. That of two beings, two worlds, two continents torn from their certainties. Jean-Baptiste Pointe du Sable, a Black man with a past as fluid as the waters of Lake Michigan, and Kitihawa, a Potawatomi woman born in the forests of the Midwest, bound to him by a bond that neither empires nor centuries could erase.

Their first moments together are unrecorded. No date, no tale. But history holds their Christian union, celebrated in 1788 in Cahokia, one of the oldest French outposts in Illinois. A marriage recorded, recognized, formalized. Yet everything suggests they were already married long before, according to Indigenous customs. In these fluid lands, where nations overlapped without always submitting, Indigenous traditions predated European sacraments. Their couple was thus first and foremost a native alliance; sacred by different codes, sealed in a language the archives do not understand.

Kitihawa (renamed Catherine in the registers) was not a mere “pioneer’s wife.” She was a partner, a broker of local alliances, a cultural mediator. By marrying a Potawatomi woman, Pointe du Sable didn’t just integrate into a native society: he embraced its worldview, its relationship to land, its social fabric. Thanks to this alliance, he was able to establish his trading post on the banks of the Chicago River, trade with various tribes, and build a prosperous farm. Far from the image of the lone conqueror, he was a man of networks, and Kitihawa was a central thread in that web.

Their union gave birth to two children: Jean and Suzanne. A new generation, born from the crossing of African and Indigenous diasporas, in a world still dominated by European ambitions. Their family, living in a wooden house with a mill, a smokehouse, a chicken coop, and a garden, formed an island of autonomy in a hostile era. Where others built forts, Pointe du Sable and Kitihawa built a home. Where others raised weapons, they traded goods, words, and traditions.

What their union represented was unsettling. It reversed the logic of domination: a non-enslaved Black man, a free Indigenous woman, united without white tutelage. Together, they embodied a historical possibility that the colonial order refused to consider: that of a world born from the margins, founded on alliance rather than conquest.

Even today, Kitihawa remains one of the most forgotten names in American history. But without her, Pointe du Sable could never have laid the foundations of Chicago. And without them, Chicago would not be what it is.

Chicago before Chicago

Drawing of Jean Baptiste Pointe du Sable’s former home in early 1800s Chicago.

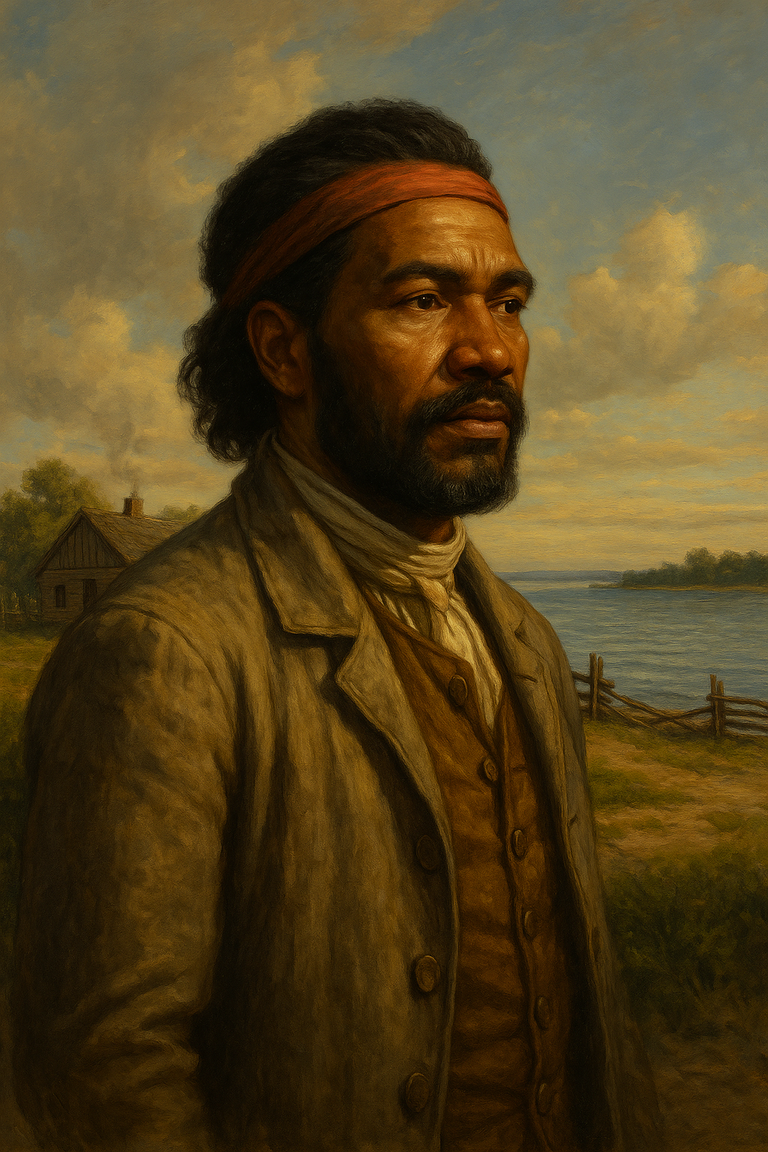

Before skyscrapers, gridded avenues, and busy business crowds, Chicago was just a crossing point. A marsh, a river, a portage. A transient place for Native peoples, a strategic shortcut between the Great Lakes and the Mississippi River. It wasn’t a city—it was a junction. And it was precisely here, in this geographical in-between, that Jean-Baptiste Pointe du Sable chose to settle.

In the 1780s, while colonial maps still sketched the continent’s interior in vague ink, Pointe du Sable recognized this site’s potential. At the mouth of the Chicago River, where freshwater meets the vastness of Lake Michigan, he built a home, then a farm, a trading post—a fully autonomous settlement. At a time when empires were warring on paper, he drew another kind of border: one of commerce, coexistence, and hospitality.

On May 10, 1790, a traveler named Hugh Heward recorded the first written trace of his presence: he bought bread, flour, and salted pork there. He traded a canoe for a pirogue. He slept under the roof of this Black man, settled there for several years already, with his family and crops.

What Pointe du Sable had built was more than a shelter. It was a complex infrastructure—agricultural buildings, outbuildings, a horse-powered mill, a main house of over 800 square feet, filled with imported furniture, paintings, and fine china. It was an economic base, but also a cultural one. A place of passage and residence. A self-organized space, independent of military structures or colonial authorities.

Later testimonies, like that of Augustin Grignon, describe a stout, prosperous man, skilled in barter, and adept at negotiating with both tribes and Europeans. His wealth didn’t come from a noble title, but from his integration into regional trade networks: he traded furs, grains, fish, livestock. He connected peoples—Potawatomis, French, British, Americans.

In this “Chicago” that wasn’t yet named as such, Pointe du Sable was inventing another way to inhabit America. A way shaped by porosity rather than walls, continuity rather than rupture. His settlement proved that a city could arise from diplomacy rather than conquest.

And yet, this original nucleus would soon be forgotten, buried under the narratives of the “real pioneers,” those who came after him but wrote the story in their own names. Kinzie, Fort Dearborn, the Treaty of Greenville—these became the official foundations. But the truth lies elsewhere: Chicago, before becoming a city, was the home of a Black man and an Indigenous woman.

Revolution and suspicion: prisoner of all causes

At the end of the 18th century, the fate of Jean-Baptiste Pointe du Sable collided head-on with the geopolitical upheavals of a changing continent. The colonial powers—France, Britain, Spain, and then the United States—were constantly redrawing territorial borders. And in this war of flags, it was the hybrid, unclassifiable figures who became suspect. Pointe du Sable paid the price.

In 1779, while living and trading at Trail Creek (now Michigan City), he was arrested by British troops. The reason? He was suspected of supporting the American insurgents—those patriots from Boston and Philadelphia defying the Crown. This Black man, educated, respected, independent, multilingual, and allied with Native nations, appeared to the authorities as dangerous. Too free. Too integrated. Too hard to control.

Taken to Fort Michilimackinac—an old French stronghold then under British control—he was imprisoned. But even there, his network of relationships spoke for him. Preserved letters show that many friends pleaded on his behalf, highlighting his integrity, loyalty, and human worth. He wasn’t convicted. In fact, he was offered a deal.

The following year, he was transferred northeast to the banks of the St. Clair River to manage a forest estate known as the Pinery, owned by British Lieutenant Patrick Sinclair. From 1780 to 1784, Pointe du Sable oversaw operations: timber management, building maintenance, local trading. He settled there with Kitihawa and their children, in a cabin near the Pine River confluence, in what would become Michigan.

This episode is central. It shows a man navigating loyalties—not opportunistically, but to survive. He wasn’t loyal to one nation, nor submissive to any authority. He embodied the figure of a go-between: among peoples, languages, laws. A man of borders—geographically and symbolically.

But this uncomfortable, nearly subversive position in a colonial world couldn’t last. Once released from his British obligations, Pointe du Sable chose to leave. He didn’t return to Trail Creek. He aimed higher, more strategically, more boldly: the site of the Chicago River. There, he would soon establish the first permanent settlement of a city destined to become one of the modern world’s beating hearts.

This carceral interlude, often downplayed in official narratives, is telling: Pointe du Sable was not a simple pioneer. He was hunted, targeted, used, displaced—a pawn in imperial struggles who, time and again, managed to reclaim control of his destiny.

Departure, disappearance, and dispossession

In 1800, Jean-Baptiste Pointe du Sable sold his property in Chicago. This flourishing farm—comprising a 22-by-40-foot house, two barns, a horse-drawn mill, a smokehouse, a bakery, a chicken coop, a subsistence garden, and high-quality furnishings—was sold for 6,000 livres tournois. The deed was signed with Jean La Lime, a Quebecois acting on behalf of a name now more widely known in official history: John Kinzie.

This departure raises countless questions. Why give up the fruit of two decades of labor? Why part with land he had built, cultivated, fortified stone by stone? Some romanticized accounts speak of wounded pride—Pointe du Sable allegedly rejected by the Potawatomis as “great chief.” Others, more political, suggest a graver theory: that American authorities, after annexing the region, demanded he purchase the land he had lived on, as if he were merely a squatter. An intolerable humiliation for a man who had made it habitable.

It’s also possible the changing geopolitical landscape convinced him to leave. The 1795 Treaty of Greenville, signed after the Northwest Indian War, had ceded large tracts of land to the United States, including six square miles around the mouth of the Chicago River. Pressure on Native populations and their allies intensified. The dream of peaceful coexistence based on exchange and diplomacy was fading.

So Pointe du Sable left. He retired to St. Charles, in the Louisiana Territory still under Spanish rule. There, he obtained permission to operate a ferry service on the Missouri River. Less prestigious, less visible, but still active. He lived for a time with his son, then with his granddaughter. His end was quieter than his life’s work. In 1818, he died in obscurity, buried without a headstone in St. Charles Borromeo cemetery. The parish register notes only one word: “negro.”

Centuries later, a granite plaque would be installed at the presumed site of his grave. But archaeological digs in 2002 found no trace of his remains. Pointe du Sable vanished as he had lived: crossing lines, eluding confinement, leaving a mark without a silhouette.

This departure should not be read as defeat, but as a sign. The sign of a man who understood, ahead of others, that official history would only remember what it wrote itself. By leaving Chicago, he wasn’t fleeing a place—he was escaping a symbolic dispossession, a planned erasure.

Some figures are enshrined in history with statues and textbooks. Others, like Jean-Baptiste Pointe du Sable, are buried on the margins, without tombstone, without epic, without voice. And yet, Chicago’s pavement rests on his memory. The port, the bridge, the city’s lines—all were born where his home once stood.

For decades, Pointe du Sable was erased in favor of John Kinzie, buyer of his house—a pioneer better suited to dominant narratives: white, loyal, documented. 19th-century tourist guides credited Kinzie with founding the city. Commemorative plaques bore his name, while Pointe du Sable remained in the shadow of what he had built. It would take until the 1930s—and pressure from African-American intellectuals—for his name to reemerge in the public space. Slowly.

Today, a school, a museum, a bridge, a park, and a commemorative stamp honor the man now called the “founder of Chicago.” But this late recognition is not enough. Because Pointe du Sable wasn’t just the first resident of a future metropolis. He was the forerunner of another America: a Creole, Afro-Indigenous America, crisscrossed by cultural flows, extraordinary solidarities, and composite identities. An America often omitted—because it contradicts the myth of white, conquering founding fathers.

Restoring the voice of Jean-Baptiste Pointe du Sable does more than right a memory. It shakes the very foundations of American history. It acknowledges that the builders of this continent also included Black men, Indigenous women, mixed-race families, and resisters without uniforms.

In every city, there is a silence.

In Chicago, that silence bore a name.

It’s time to hear it.

Sources

- Dominic A. Pacyga, Chicago: A Biography, University of Chicago Press, 2009.

- Milo Milton Quaife, Checagou: From Indian Wigwam to Modern City (1673–1835), University of Chicago Press, 1933.

- Juliette Kinzie, Wau-Bun, The “Early Day” in the Northwest, Derby and Jackson, 1856.

Table of Contents

- A man, a city, an erased memory

- The unknown with many faces

- Kitihawa and the clash of worlds

- Chicago before Chicago

- Revolution and suspicion: prisoner of all causes

- Departure, disappearance, and dispossession

- Sources