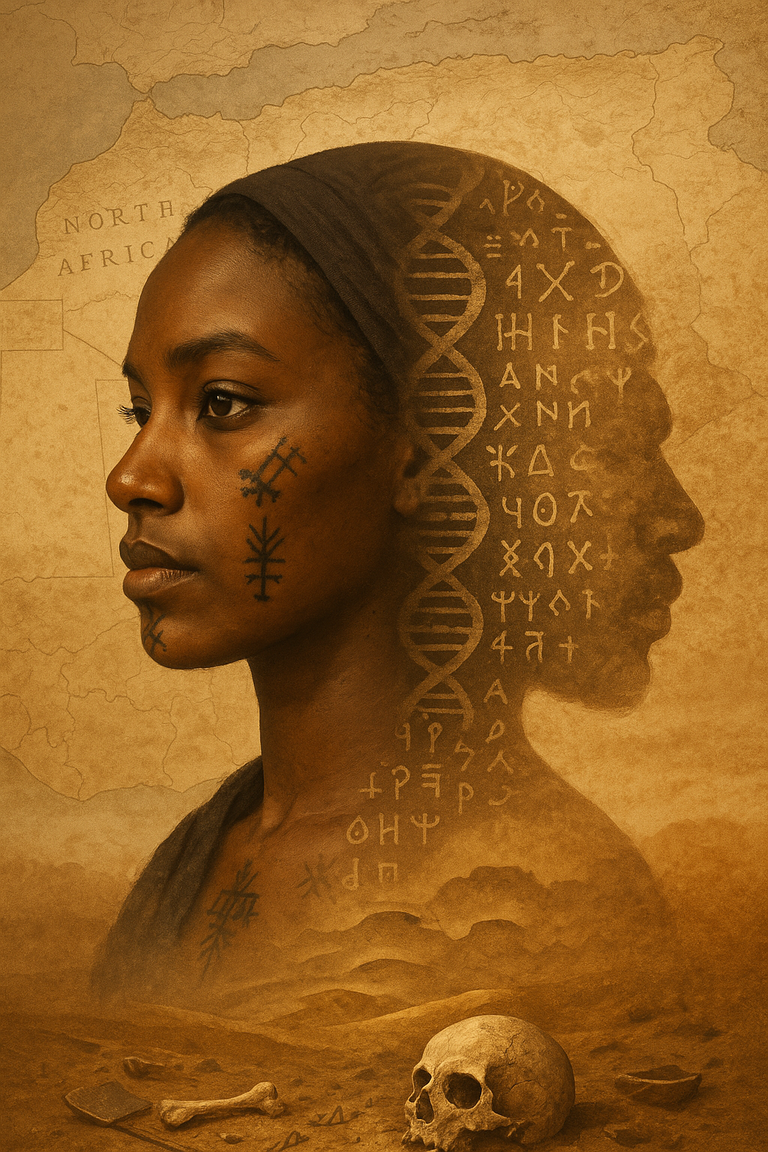

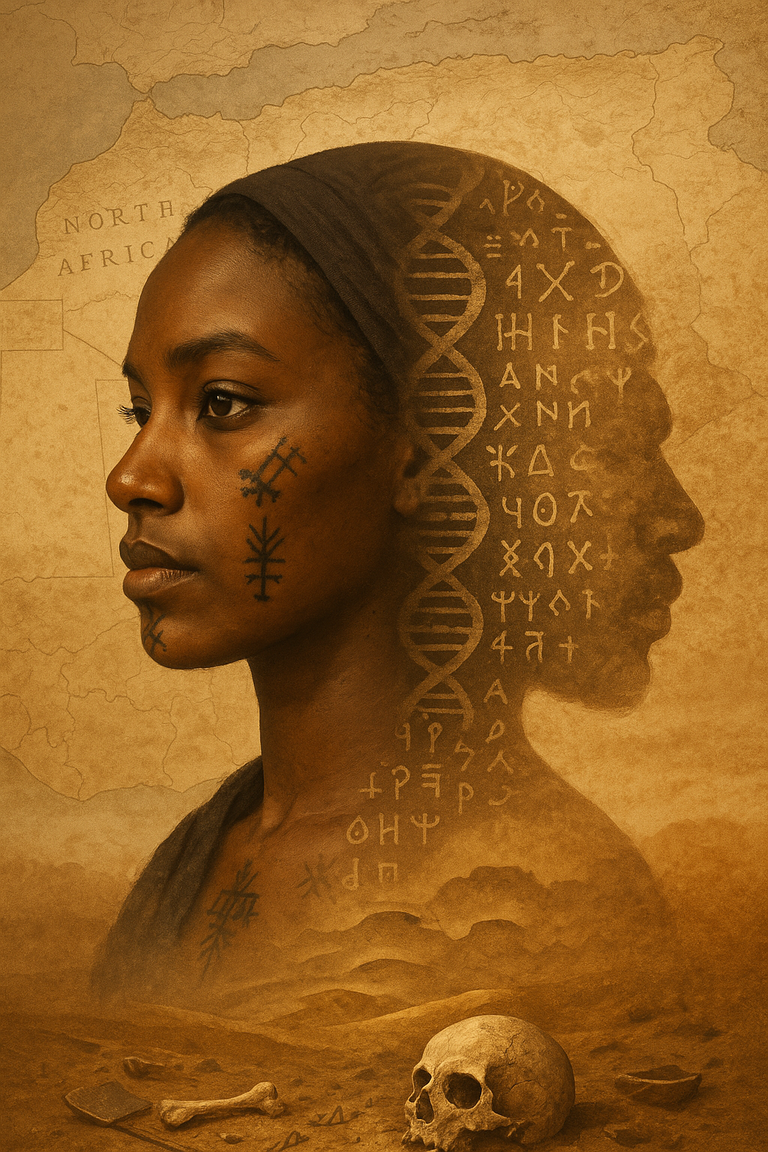

For centuries, North Africa was a crossroads of Black peoples, long before slavery or colonization. This article unveils the repressed history of the deep African origins of the Maghreb. Between genetics, linguistics, and popular memory, a reconciliation is long overdue.

Rewriting the black history of North Africa

Beneath the sands of the Sahara, a memory resurfaces. A memory of a continent that was once torn from itself.

Every time we draw a map of Africa, an invisible line embeds itself in our minds: the Sahara, a supposed border between two worlds. To the north, a white, Arab, sometimes Mediterranean Maghreb. To the south, a Black, tropical, “sub-Saharan” Africa. This arbitrary separation is repeated everywhere: in textbooks, media, scholarly discourse, and geopolitical rankings. It seems so natural that few question it. Yet it has no historical or scientific basis.

The desert was never a wall. It was a corridor, a lung, a bridge. Long before empires and caliphates, before Rome or Carthage, North Africa was inhabited by men and women with Black skin. They hunted, carved, engraved, counted, and built. They invented pottery, navigation, numeration, bows, and funerary rites. They planted the first seeds of the world as we know it. And yet, their memory has been swept away like the sands of El Djouf.

Because one of the greatest erasures in human history doesn’t just happen in libraries—it happens in representation. What people were led to believe was that North Africa had always been white. That Black history only began south of the desert. That the first Egyptians, Maghrebians, or Canaanites could not have been dark-skinned. That Black people today are “visible minorities” in the region, as if their presence were marginal, imported, or recent.

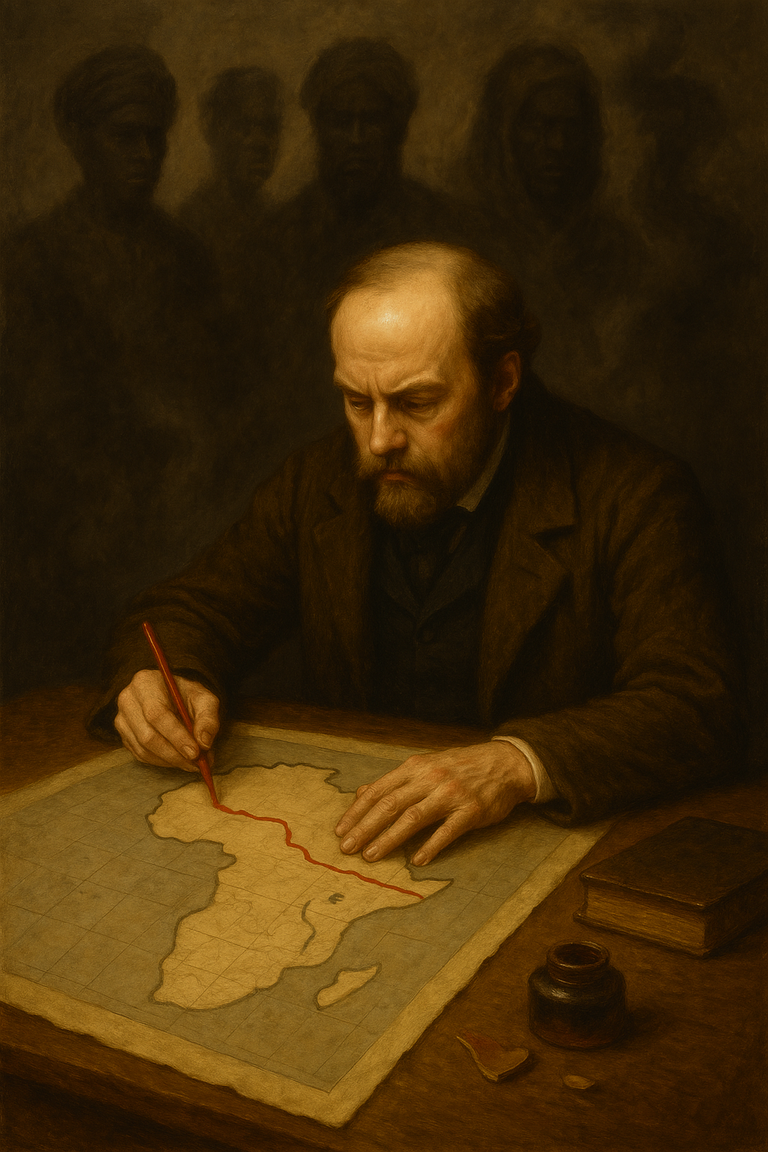

This falsification rests on two pillars: the power of imperial narratives and the complicity of postcolonial educational institutions. For the past century, an avalanche of “truths” has buried archives, bones, genomes: that the first Berbers were Caucasian, the Pharaohs came from the Levant, Saharan peoples were always Arab. Representations spread through doctored statues, biased studies, misleading maps, and the suppression of the latest scientific data.

But today, DNA speaks. And so do stones. Researchers from the Max Planck Institute, Harvard, Cambridge, Rabat, Leipzig, CNRS, Khartoum, Tunis, and Oxford have shown: the first North Africans were Black. The Natufians of Palestine were Black. The Capsians of the Sahara were Black. The first Greeks had sub-Saharan genetic input. The earliest Maghrebians had neither light skin genes nor blue eyes. All of this is documented—and all of it disturbs.

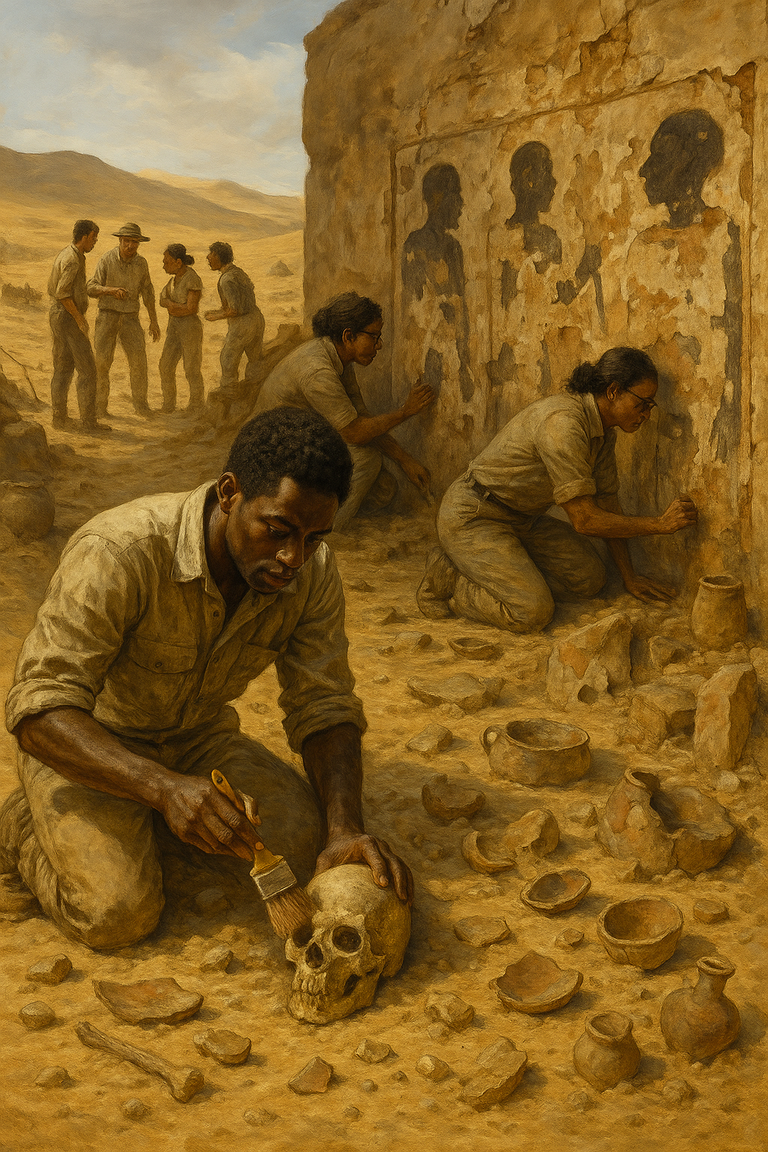

What this text proposes is not a militant narrative: it’s a return to truth. An archaeological, genetic, linguistic, and historical synthesis of the African origins of North Africa. A rigorous dismantling of falsifications. A rehabilitation of peoples erased for far too long. A journey into the first Black humanities of the Mediterranean.

North Africa was not always white. In fact, it never was at its origins.

Genealogy of an erasure

It all starts with a simple yet explosive question: who has the right to tell the story of origin? In dominant historical narratives, North Africa is often placed on the “wrong” side of the map. Neither fully African, nor fully Arab, nor truly Mediterranean, it floats in a gray zone—an ideological no-man’s land quickly occupied by colonial powers, nationalist intellectuals, and orientalist narratives. The result: a region torn from its own historical depth.

Yet Africa is the cradle of humanity. This once-contested fact is now firmly established. From 300,000-year-old Homo sapiens fossils found at Jebel Irhoud (in Morocco), to migrations out of the continent via the Nile and the Red Sea, all evidence shows that the first human societies were born and raised here. But as one nears North Africa, the narrative spirals. What is African suddenly stops being Black. What is ancient becomes Eurasian. What is indigenous is painted white.

The division between “Black Africa” and “White Africa” is a late invention. It was born in the 19th century, in the writings of European geographers. This racial split has no archaeological, linguistic, or anthropological basis. It served a clear goal: to legitimize colonial domination by arguing a “natural” difference between the supposedly more civilized peoples of the north and the allegedly more primitive peoples of the south. A hierarchy justifying a civilizing mission on one side and prolonged tutelage on the other.

This fictional border was uncritically adopted by postcolonial administrations eager to solidify their power on “national” and homogeneous foundations. Thus, states like Morocco, Algeria, or Tunisia long concealed the sub-Saharan roots of their populations. Elites whitewashed founding myths, denied internal slavery, dismissed Fulani, Hausa, and Toubou heritages, and erased Black populations living in oases, Saharan margins, or urban centers.

Yet another tool of domination added to this falsification: science—or rather, a biased science. For a long time, genetics was used to “prove” a European or Levantine origin for the first Maghrebians. Some studies, based on skewed samples or questionable protocols, led to false conclusions. Worse still: more rigorous studies revealing significant sub-Saharan genes in ancient populations were marginalized or excluded from mainstream publications.

This is how erasure operates: politically, culturally, visually, genetically. Early African pottery? Ignored. Neolithic Saharan peoples? Lost in ethnic ambiguity. Black mummies of Upper Egypt? Recolored in museums. DNA results of the Iberomaurusians? Delayed, downplayed, bypassed.

Yet the data exists. It’s there. We just need the courage to face it.

The history of North Africa begins not with Carthage, Rome, or Islam—but in the valleys of the Nile, in the caves of Taforalt, on the banks of the Pine River or Kom Ombo. It begins with Black men and women who shaped the first civilizations of the continent—and of the world.

The african paleolithic: Cradle of the black peoples of the North

Long before the Pharaohs, before the pyramids pierced the sky, the Nile Valley already echoed with the footsteps of Black peoples. These Upper Paleolithic communities, established across present-day Sudan, Egypt, and southern Sahara, left traces of a cultural richness that modern narratives have often ignored or displaced beyond the continent.

One of the most significant sites is Jebel Sahaba, in northern Sudan, near the Egyptian border. Dated to about 13,000–14,000 BCE, this necropolis contains the remains of at least 61 individuals. But it’s not the number that surprises—it’s the brutality of the wounds found on their bones. These marks indicate a large-scale armed conflict, the oldest known to date. Yet far from the primitive stereotype, these people had social organization, funerary rituals, and collective burials. A symbolic world already in motion.

Farther north, in Nazlet Khater, Upper Egypt, researchers unearthed a human skull dated to 35,000 years ago, alongside flint tools. Morphological analyses are clear: this was a man with unmistakably “Negroid” features. Contemporary to the earliest European Homo sapiens, he had a similar cranial capacity, but a distinctly different origin. He confirms a long-standing, autonomous Black presence in the Nile Valley.

Same at Wadi Kubbaniya, where hunter-gatherer camps over 17,000 years old reveal advanced grinding tools, microlithic technologies, and a diverse diet. Here lie the early signs of sedentarization, long believed to be exclusive to the Fertile Crescent.

The Nile Valley, then, is not merely a corridor to the Orient or the North—it is a civilizational matrix. Here, before writing, agriculture, or cities, the world as we know it began.

While the Nile fostered stable human settlements, another vast and dynamic stage developed: the Sahara. Far from being dry and barren, between 11,000 and 4,000 BCE, it was a lush region of savannas, lakes, and open forests. A Green Sahara, rich with rivers, animals—and Black humans.

At Nabta Playa, in southern Egypt, archaeologists uncovered a megalithic calendar 6,000–7,000 years old, older than Stonehenge. Also found were ritual cattle burials, circular villages, and a complex social organization. These were Black pastoralist peoples, genetically related to Nilotic groups in South Sudan.

In the Tassili n’Ajjer mountains, between present-day Algeria and Libya, thousands of rock paintings depict Black men and women with elaborate hairstyles, spears, bows, and domestic animals. Dated between 10,000 and 4,000 BCE, these works are unique records of Black African societies in what is now the desert.

And we could cite Tadrart Acacus (Libya), Gobero (Niger), Taghit (Algeria), Farafra (Egypt), El Adam (Mauritania)—all sites showing that the Sahara was once the cradle of a proto-civilization, deeply Black, connected to the Nile, Sahel, and Maghreb long before Berbers, Arabs, or Europeans arrived.

These so-called “Neolithic” peoples were not just bearers of technology. They embodied an imagination, a mythology, a relationship to time and nature. They shaped an ancient Black civilization—little known because it is unsettling.

Unsettling—why? Because it challenges a deeply rooted idea: that North Africa is naturally separated from the rest of the continent. Yet here, everything shows a continuous cultural, biological, and geographic flow between North, South, and Central Africa.

The African Paleolithic is not a secondary prologue to human history. It is a foundational act. And it was Black.

Taforalt, Afalou, and the Iberomaurusians

If Africa is the cradle of humanity, then the western Maghreb is one of its oldest bastions. On its rocky cliffs and millennia-old caves, the bones still speak—and today, they speak louder than ever. For it is no longer just archaeology uncovering ancestral memory, but ancient genetics shaking up established dogma.

At Taforalt, in northeastern Morocco, in a cave overlooking the Mediterranean, human burials dated between 15,000 and 18,000 years ago have been excavated. These remains belong to the Iberomaurusian people, considered one of the first sedentary groups in the Maghreb. For a long time, they were presumed “Mediterranean” or “proto-European” based on their tools and weak morphological theories. But DNA analyses published in 2018 in Science overturned all that.

These individuals’ genomes show predominantly sub-Saharan ancestry, coupled with a small percentage of very ancient so-called “Eurasian” elements (from populations that returned to Africa from the Levant 30,000 to 40,000 years ago). Most striking is the significant presence of genes linked to dark skin pigmentation, Nilotic features, and the absence of markers for light skin or light eyes.

In other words: the first known inhabitants of Morocco were not “Caucasian Berbers” or “Phoenicians,” but biologically Black Africans. They laid the foundations for future North African populations. Their genome still persists—albeit faintly—in some rural Maghreb communities today.

Farther east, on Algeria’s coast, the Afalou bou Rhummel caves—discovered in the 1950s—contained skulls dated between 11,000 and 13,000 years ago. Early researchers classified them in a vague category: “Cro-Magnon-Africanoid mix,” using racist taxonomies still in fashion at the time.

But recent DNA analyses, cross-referenced with morphometric and isotopic data, reveal a more coherent picture: the Afalou people are directly linked to the Iberomaurusians of Taforalt and thus to an ancient sub-Saharan lineage that spread throughout central Maghreb until the Neolithic.

These populations already mastered funerary symbolism, body decoration, coastal resource management, fishing, and seasonal foraging. They were neither marginal nor primitive. They constituted a self-contained world—a structured, mobile, technical Black African world connected to both the Sahel and the Mediterranean.

Yet this lineage is precisely what history tried to erase—because admitting that the foundations of Maghrebian humanity are Black overturns centuries of racial hierarchies.

The discovery of the Y-chromosome haplogroups carried by Iberomaurusians supports this. One of the most frequent paternal haplogroups, E-M78, is now common among Egyptians, Ethiopians, Sudanese, and Sahelian populations. It is a sub-Saharan marker present among Afro-descendant groups in North Africa—often minimized in national narratives.

As for mitochondrial haplogroups (maternal lineage), they reveal deep ties with populations south of the Sahara and in the Horn of Africa. This ancient mix, overwhelmingly African in origin, reflects internal continental migrations—not hypothetical “Caucasian invasions.”

In other words: genetically, the Maghreb has been African for millennia. And this Africanness was deeply Black in its earliest human expressions.

But this genetic truth is too subversive for the comfort of fixed identities. It challenges civilization-whitening narratives, fantasies of European ancestry, and racialized discourses that marginalize Blackness. It reminds us that even the cradle of the Berbers is African—and that their identity, far from being monolithic, was shaped by a founding diversity in which Blackness was central.

From the black Pharaoh to the Almoravids

At the dawn of the first millennium BCE, a Black army descended the Nile, banners raised high, war drums echoing through the valleys of Upper Egypt. At its head was Piankhy (or Piye), king of the Kingdom of Kush, son of ancient Sudan. He came not to plunder, but to claim the legacy of his ancestors—the temples, the gods, the laws. He did not arrive as a foreign conqueror, but as a rightful heir.

In 730 BCE, Piankhy conquered Lower Egypt, unified the Nile Valley, and founded the 25th Dynasty—what the Egyptians would call the “Ethiopian Dynasty” (in the classical sense: the Black Dynasty). For nearly a century, his successors—Shabaka, Taharqa, Tanutamon—ruled a territory that stretched from modern-day Sudan to the Nile Delta.

The iconography of these pharaohs is striking: broad faces, full lips, wide noses, tightly curled hair beneath royal headdresses. Colossal statues, Karnak bas-reliefs, frescoes from Napata or Meroë leave no doubt about their African identity. Taharqa would even be hailed by the Assyrians as one of their fiercest opponents.

Why is this episode so often sidelined in ancient history? Because it clashes head-on with the image of a white, Hellenized, Mediterranean Egypt. Yet Egypt, in its deepest roots, was a Black Nilotic civilization—founded by peoples who came from the south, not the north.

And this legacy, the Kushite rulers never denied. They revived it, preserved it, sanctified it.

A thousand years later, another southern force shook the North: the Almoravids, desert warrior-monks who built one of the greatest medieval empires of Africa. Their origin? The Sahara—specifically, the borderlands between Black Mauritania and southern Berber populations.

Their founder, Abdallah Ibn Yassin, preached a strict form of Islam among the Sanhadja and Lemtouna tribes. But it was the Black Guinean peoples of Tekrour and the tribes of present-day Mauritania who formed the first military forces of the movement. Historian Ibn Khaldun himself noted the strong presence of “Blacks” in the Almoravid army.

In 1055, they seized Audaghost, a strategic Saharan city. In 1062, they founded Marrakech, future imperial capital. Within a few decades, the Almoravid empire stretched from Senegambia to Al-Andalus, cutting across the Maghreb like a Sahelian lightning bolt.

The most famous of these rulers, Yusuf Ibn Tashfin—venerated as a great king of Islam—was described by contemporaries as dark-skinned and from the South. At his side, Black elites were not the exception—they held real power: in caravan trade, religious scholarship, and governance.

This Sahelian continuity, linking the Black kingdoms of the Niger (Ghana, Tekrour) to the dynasties of the North, is systematically erased in modern national narratives. Yet the historical DNA of the Maghreb is as Sahelian as it is Amazigh or Mediterranean.

The Kushite episode and the Almoravid rise reveal the same phenomenon: the periodic emergence of Black power in North Africa—asserting legitimacy, culture, and worldview.

But each time, these moments are whitewashed in hindsight: Egypt “forgets” its Black dynasty. The Maghreb “re-whitens” the Almoravids. Colonial Europe—and later postcolonial nation-states—have every interest in turning North Africa into a bulwark against the “Black continent” rather than acknowledging its full participation in its history.

This artificial divide between “Black Africa” and “White Africa” holds no water—historically, genetically, or culturally. It is an ideological product.

The truth is that the boundaries between Maghreb and Sahel were long porous, shifting, and brotherly—long before Europe arrived.

The obsession with historical whitening

The notion of a Maghreb fundamentally distinct from sub-Saharan Africa is a late construction—born from European colonial narratives. Before the 19th century, no rigid border in classical Arabic texts or African oral traditions separated “White Africa” from “Black Africa.” The Sahara was a bridge, not a wall.

But with French, British, and Spanish colonization, this continuum was broken. France, in particular, developed an ideology of “useful Africa,” in which Algeria, Tunisia, and Morocco were seen as Latin extensions—civilizable, nearly European—while Black Africa was portrayed as primitive, savage, in need of taming.

This racialized narrative relied on deliberate historical falsifications:

- Overemphasizing “white” or “oriental” origins of Maghrebi populations.

- Erasing Black dynasties, Sahelian intermingling, and ancient African presences.

- Redrawing mental maps to separate what had always been linked.

Thus, historical whitening of the Maghreb is not based on evidence, but strategy. It denies the African identity of the North to better dominate the South—and to create a lasting identity divide among African peoples.

This falsification shows up in tools of knowledge transmission. Maghrebi and French school textbooks still present a heavily biased view of North African population history.

In history books:

- Berbers (or Imazighen) are sometimes described as “Caucasoid”—a pseudoscientific racial model.

- Dynasties like the Almoravids or Kushites are sidelined or rewritten to appear lighter-skinned.

- Sahelian African influences are minimized—or absent altogether.

- When Black Africa is mentioned, it’s often framed as external or foreign.

Worse still, some books refer to ancient “Negroid invasions,” parroting the racial lexicon of the 19th century.

The result is a constructed amnesia: entire generations grow up unaware that their history is as Black as it is Berber or Arab, as Sahelian as it is Mediterranean.

Beyond words, imagery plays a major role in whitening. Visual representations in museums, documentaries, and films betray a racist imaginary: Pharaohs are white, Berbers are light-skinned, Muslim dynasties are Europeanized.

This visual revisionism is one of the most powerful—because it shapes collective memory. One need only watch a TV show about ancient Egypt or open an illustrated history book to see that Black people are always shown as slaves, servants, or foreigners.

Yet ancient iconography—frescoes, sculptures, steles—tells another story: Black peoples were present as rulers and builders. But the dominant image refuses this truth.

Repressed memories, struggling identities

In contemporary Maghrebi societies, Black populations are often caught in a double erasure: historical erasure, through their absence in official narratives, and social erasure, through marginalization in economic and cultural life.

The descendants of enslaved people—known as Haratin, Abid, or Gnawa, depending on the region—carry the stigmas of an unacknowledged past. Many are unaware of their own history. Few textbooks, museums, or public discourses mention their roles in dynasties, the economy, religion, or the arts. In their place: silence, suspicion, or folklorization.

This invisibility is no accident. It is the product of a rewritten history, of elites who chose to adopt symbolic whiteness to align with colonial Europe, and of latent racism inherited from the Ottoman period, European stereotypes, and distorted religious interpretations.

But today, that memory is returning—slowly, from the ground up.

Over the past two decades, a generation of activists, historians, artists, and writers from North Africa—whether Black themselves or not—has worked to restore this suppressed memory:

- In Mauritania, the abolitionist movement IRA combats slavery, which still exists in practice in some areas.

- In Morocco, artists like Hajja El Hamdaouia and Maâlem Mahmoud Guinia have popularized Gnawa music, deeply rooted in Black African culture.

- In Algeria, historians are rediscovering the role of Black soldiers in Emir Abdelkader’s armies.

- In Tunisia, descendants of enslaved people have only recently begun commemorating the 1846 abolition, asserting a Black Tunisian memory.

- In the diaspora, children of displacement are producing powerful narratives: autobiographies, essays, documentaries, and music that break the silence.

This voice is sometimes unsettling. It disrupts rigid identity narratives founded on homogeneous notions of Arabness or Berberness. But it is necessary—because it says one essential thing: we cannot understand the present without confronting the repressed past.

Repairing history does not mean reversing it. It’s not about saying everything was Black—but about recognizing that North Africa has always been a place of mixing, circulation, and African interaction. It’s about reconciling the Maghreb with its sub-Saharan component—and ending the opposition of two worlds that have always coexisted and co-created history.

That requires several concrete actions:

- Reforming school curricula to include the Black memory of the Maghreb.

- Creating museums, forums, research centers, and archives.

- Honoring historical Black figures—from Pharaoh Taharqa to the king of Tekrour, to Jean-Baptiste Pointe du Sable, founder of Chicago.

- Decolonizing collective imagination by restoring dignity to forgotten faces, names, and stories.

The stakes are enormous. Because beyond memory, it is the future of African societies that is at play. An Africa fragmented by colonial ideologies cannot assert sovereignty. An Africa that does not know its past is easy prey for all forms of domination.

Returning to the north without denying the south Sud

The desert forgets nothing. Beneath its dunes, in its caves, through its winds, it preserves the traces of a plural, mixed North Africa—shaped for millennia by human flows from the Nile, Niger, Congo, and Chad. A Black North Africa, too—one that dominant history tried to erase.

What archaeology, genetics, linguistics—and also music, surnames, rituals, and popular tales—reveal is a truth that common sense always knew: Africa is one. Its peoples have always circulated, always spoken to one another, loved, fought, and united.

To deny this is to uphold colonial partitions. It is to fuel absurd racial hatreds. It is to deprive new generations of a shared historical foundation.

But restoring this history means rearming consciences. It means allowing a Gnawa girl to understand that her voice is ancestral. A Haratin boy to walk tall in the streets of Rabat, Nouakchott, or Algiers. A Black student in Tripoli to no longer wonder if he is “home.”

This is not about rewriting history. It is about repairing it.

And that repair begins here: in reclaimed words, in forgotten figures returned to their rightful place, in reconnected links between Cairo and Timbuktu, between Tamanrasset and Lagos, between Carthage and Gao.

Because in the end, there can be no decolonized future without reconciled memory.

Sources

- Ke Wang et al., High-coverage genome of the Tyrolean Iceman reveals unusually high Anatolian farmer ancestry, Cell Genomics, Vol. 3, 2023.

- Marieke van de Loosdrecht et al., Pleistocene North African genomes link Near Eastern and sub-Saharan African human populations, Science, 2018.

- Rosa Fregel et al., Ancient genomes from North Africa evidence prehistoric migrations to the Maghreb, PNAS, 2018.

- Fulvio Cruciani, Human Y chromosome haplogroup R-V88: a paternal genetic record of early Holocene trans-Saharan connections, European Journal of Human Genetics, 2010.

- Eugenia D’Atanasio et al., The peopling of the last Green Sahara, Genome Biology, 2018.

- Daniel Shriner, Genetic history of Chad, American Journal of Biological Anthropology, 2018.

- Iosif Lazaridis et al., Genomic insights into the origin of farming in the ancient Near East, Nature, 2016.

- Cheikh Anta Diop, Antériorité des civilisations nègres, Présence Africaine, 1967.

- Martin Bernal, Black Athena, Vol. III – The Linguistic Evidence, Rutgers University Press, 1987.

Summary of sections

- Rewriting the Black History of North Africa

- Genealogy of an Erasure

- The African Paleolithic: Cradle of the Black Peoples of the North

- Taforalt, Afalou, and the Iberomaurusians

- From the Black Pharaoh to the Almoravids

- The Obsession with Historical Whitening

- Repressed Memories, Struggling Identities

- Returning to the North Without Denying the South

- Sources