On May 8, 1902, Mount Pelée obliterated Saint-Pierre in seconds, claiming 30,000 lives in a torrent of fire and ash. Behind this tragedy lies the violent awakening of a volcano, but also political blindness, the weight of colonial interests, and the abandonment of a powerless Martiniquais population. With precision and depth, Nofi recounts the story of the deadliest natural disaster in French history and questions what it still reveals today about our relationship to power, knowledge, and memory.

When mount Pelée devoured the little Paris of the antilles

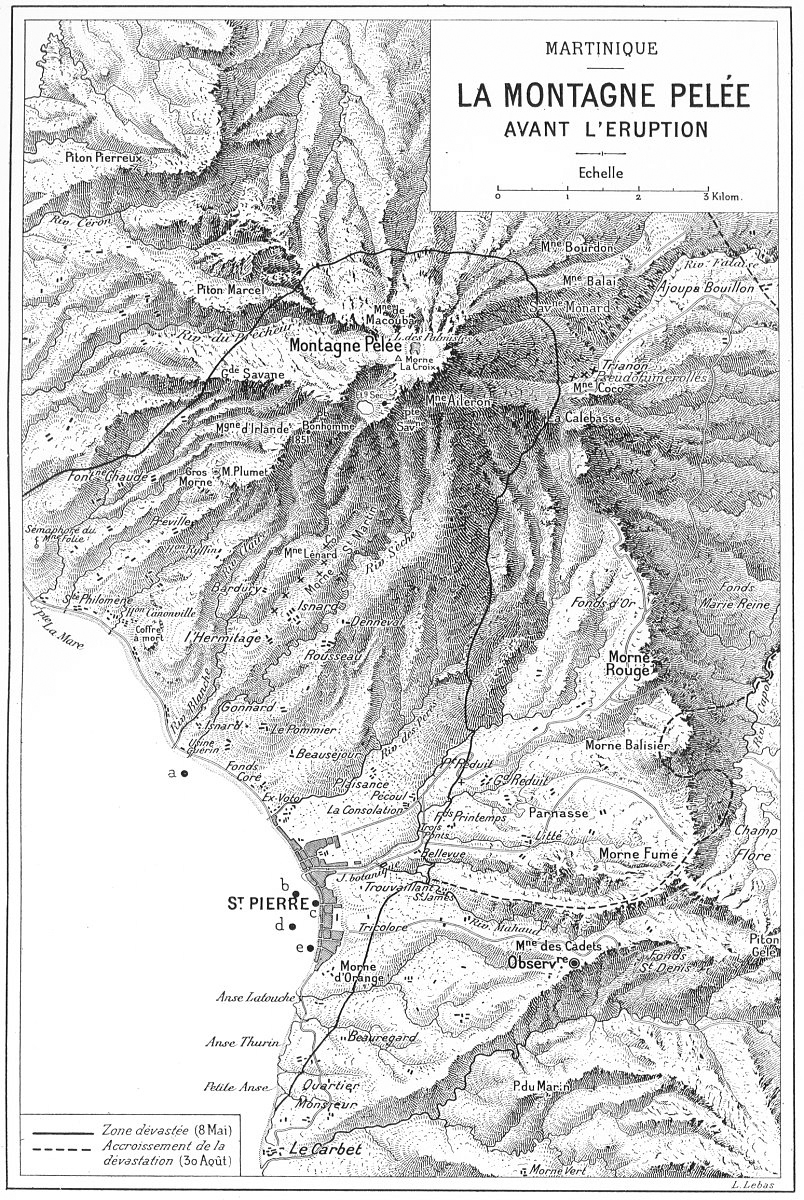

In the north of Martinique, Mount Pelée looms—silent sentinel of an archipelago caught between tropical splendor and colonial memory. On May 8, 1902, at 7:52 a.m., the volcano unleashed a pyroclastic surge that, within minutes, annihilated Saint-Pierre. Over 30,000 lives were extinguished. The city leveled.

It was not an apocalypse—it was a reckoning: the judgment of an era blinded by illusions of grandeur and deaf to the warnings of the land and its people.

ut the story does not begin that day. It unfolds in layers, like the geological strata of still-warm lava. Each layer conceals an unspoken truth: political, social, scientific.

Before it became a field of ruins, Saint-Pierre was the jewel of the French Antilles. It was nicknamed the “Little Paris”—a name steeped in colonial imagination, aiming to render this volcanic island familiar through a Haussmannian lens. Cathedral, theater, high school, chamber of commerce, printing press… everything seemed to proclaim its continuity with the metropole.

And yet.

Beneath the glossy veneer of Creole façades, Saint-Pierre was a fractured city. The white Creole elite (the békés) dominated the sugar economy. Descendants of slaves—freed in 1848—made up a laboring majority, confined to subordinate roles. Racial hierarchy had not been abolished—it had simply changed form.

This underlying tension, this imbalanced normality, foreshadowed the tragic irony of 1902: a society so confident in its superiority that it ignored the mountain’s warnings.

As early as February 1902, Mount Pelée spoke. Acid fumaroles, tremors, the smell of sulfur, showers of ash—signs the Earth sends to those who know how to listen. But in the salons of Saint-Pierre, the dancing continued. Preparations were underway for the second round of legislative elections, scheduled for May 11. Governor Louis Mouttet remained firmly convinced: no panic, no evacuation.

On May 5, the first tragedy struck: a lahar (a scorching mudslide) engulfed the Guérin sugar factory. 23 dead. Venomous ants and deadly snakes (the terrifying fer-de-lance) invaded the city. Nature screamed. The administration, however, issued reassuring bulletins.

Order had to be maintained. The elections had to proceed. The illusion had to be preserved.

7:52 a.m. The sky split open. A supersonic explosion released a 1,000°C pyroclastic cloud, racing down the volcano’s slopes at over 500 km/h. Within two minutes, Saint-Pierre was reduced to silence. Houses ignited. Ships in the harbor melted in the heat. Thousands of men, women, and children vanished without a sound.

The pyroclastic surge left no survivors. It was neither fire nor smoke—it was judgment. It was not a natural disaster—it was political. It wasn’t the mountain that killed, but the refusal to evacuate, the blindness of the administration, the obsession with the electoral process.

Governor Mouttet died alongside his wife. In a final irony, he had returned to the city “to reassure the population.”

Three names rose from the ashes—like fists raised against oblivion.

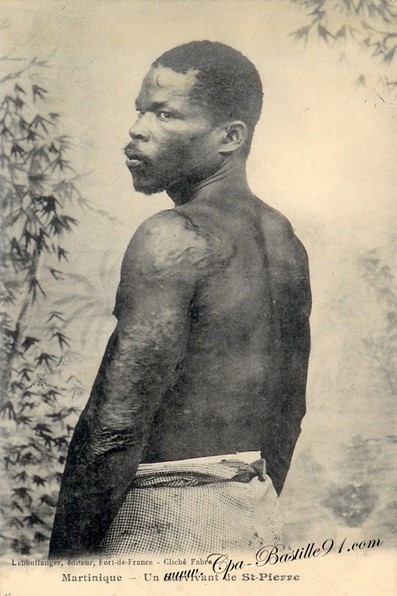

Louis-Auguste Cyparis, a young Black man imprisoned in a dark cell. Shielded from the flames by the thick stone walls, he survived—burned and mutilated. He later became a circus attraction in the United States, exhibited as “the man who saw hell.”

Léon Compère Léandre, a cobbler, survived on the edge of the devastated zone.

And Havivra Da Ifrile, a child who fled to sea in a small boat, savior of her own legend.

Their stories are the human counterweights to a dehumanized catastrophe. They remind us that history does not entirely kill those who bear witness.

Help arrived late. The ship Suchet anchored in the bay at 3 p.m., delayed by the heat. It rescued the few survivors found at sea. In Fort-de-France, refugees crowded together. The colonial government, overwhelmed, sent them back in August for lack of resources.

President Roosevelt sent food. Europe donated money. A wave of solidarity—but no self-critique. No trial. The volcano remained a “natural tragedy.” Human error was dissolved in posthumous heroism.

From this cataclysm, a new science was born: modern volcanology. American geologists Jaggar, Heilprin, Perret, Lacroix—all converged on Martinique. Lacroix coined the term nuée ardente, and gave the world “Pelean eruption.”

Mount Pelée became a fiery laboratory. Each crater, each layer, each scorched rock became data. Science advanced—but memory remained ashen.

In 1929, the volcano erupted again. This time, the population was evacuated. No deaths. A reckoning with blindness.

Today, Saint-Pierre is a peaceful town, labeled a “City of Art and History.” Visitors come to dive among sunken wrecks. They visit the theater ruins, Cyparis’ cell. Tourism celebrates the past—but the scars are visible.

The city never fully recovered. Fort-de-France took its place. Saint-Pierre became a memorial, frozen in the moment of its downfall.

The volcano still sleeps. In December 2020, abnormal activity was detected. Nothing alarming, scientists said. But the island has learned to read the signs.

The eruption of Mount Pelée is more than a geological event. It is a revealer of systems: social inequality, implicit racism, political incompetence, deafness to the living. The victims were poor, Black, powerless. They had no voice. Literally.

In a time of escalating climate disasters, this story holds up a mirror. What do we do with warning signs? Whom do we protect when nature speaks? And above all: who dies when we choose to do nothing?

The mountain and the memory

May 8, 1902 is not over. It repeats every time we treat nature as metaphor instead of as interlocutor. Every time we sacrifice the most vulnerable on the altar of power.

Mount Pelée did not merely destroy a city. It exposed a society. It made visible what colonial palaces tried to hide: the contempt of the powerful, the arrogance of bureaucracy, and the fragility of dominated lives.

And still today, in the silence of its fumaroles, the mountain invites us to listen to what we refuse to hear.

Bibliography

- Lacroix, Alfred, La Montagne Pelée et ses éruptions, Paris, Masson et Cie, 1904.

- Perret, Frank A., The Eruption of Mount Pelée (1929–1932), Carnegie Institution of Washington, 1935.

- Heilprin, Angelo, The Tower of Pelée: New Studies of the Great Volcano of Martinique, Philadelphia, J. B. Lippincott Company, 1904.

- Tanguy, Jean-Claude, “Les éruptions de la montagne Pelée (1902-1905): anatomie d’une catastrophe,” Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research, vol. 60, 1994, pp. 87–107.

- Chrétien, Simone & Brousse, Robert, La Montagne Pelée se réveille: Comment se prépare une éruption cataclysmique, Paris, Éditions Boubée, 1988.

- Rives, Claude & Denhez, Frédéric, Les épaves du volcan, Glénat, 1998.

- Confiant, Raphaël, Nuée ardente, Paris, Mercure de France, 2002.

- Hess, Jean, La Catastrophe de la Martinique: notes d’un reporter, Paris, Charpentier et Fasquelle, 1902.

- Drouet, Francis, Notes sur la Martinique, Rouen, Imprimerie Cagniard, 1902.

Summary

- When Mount Pelée Devoured the Little Paris of the Antilles

- The Mountain and the Memory

- Bibliography