In Montevideo, he was born without a name. In Rome, he died a hero. Andrés Aguiar, a freed slave turned lieutenant of Garibaldi, crossed two continents and two revolutions. But it took more than a century for his name to finally reemerge from the margins of History.

Montevideo, 1810: Born in chains

In the dusty alleys of early 19th-century Montevideo—a port city torn between imperial ambitions and emerging independence movements—a Black child is born, a product of the slave system that then structured all of Latin America. Andrés Aguiar, like so many others, comes into the world in an imposed condition of inferiority: that of movable property, someone else’s possession. His name, inherited not from his ancestors but from his presumed master (Uruguayan General Félix Eduardo Aguiar), is already an indication of this initial dispossession, of this identity stolen by history.

Little is known about Aguiar’s early years. Archives are silent on lives deemed unimportant. But through fragments preserved by historians, emerges the image of a robust, agile young man, an excellent horse tamer; an ancestral knowledge inherited from African and Creole communities of the eastern countryside. At a time when the ability to handle a horse could make the difference between servitude and survival, Aguiar builds a reputation as a skilled rider, respected even within military ranks.

But the essence of his journey would unfold amid the clamor of weapons and the turbulence of the Guerra Grande (1838–1851), a brutal conflict between supporters of the Montevideo government and federalist forces backed by Argentina’s Juan Manuel de Rosas. It is in this context that freedom is likely granted to him; not as a right, but as a war strategy. In 1842, both sides proclaim the emancipation of slaves in hopes of bolstering their ranks. Nearly 5,000 men are thus freed to serve the homeland… or at least, their leaders’ ambitions.

Freed from his chains but not yet master of his destiny, Aguiar aligns himself with another outcast: Giuseppe Garibaldi, an Italian adventurer exiled on the banks of the Río de la Plata, bearer of a nascent republican and universalist ideal. Garibaldi, then commander of the Italian Legion, attracts around him a motley cohort of fighters: European exiles, gauchos, freed Blacks. Andrés Aguiar joins him; a gesture that, for him, is as much about survival as it is about faith in a new idea: that weapons can pave the way to freedom.

Garibaldi, in his memoirs, speaks of these men with uncommon admiration for the time. He describes Aguiar as a trustworthy companion, loyal, calm, courageous, endowed with exceptional composure. To him, this former slave is not just a soldier: he is a figure, a symbol, a living embodiment of the liberation ideal for which he fights.

Thus, in Uruguay, not only is the soldier Aguiar born, but also the myth; that of a man who, having lost everything at birth, gradually gains what the Republic itself promised to everyone: honor, recognition, and the right to die standing.

Uruguay at war: baptism by fire

In the heart of the 1840s, Uruguay is a constant battlefield. Montevideo, encircled for years by the troops of Manuel Oribe (ally of Argentine dictator Rosas), resists with desperate energy. In its cobbled streets, a heterogeneous army, nicknamed the “Defense Government,” fights for its survival. Alongside them, foreigners flock, not driven by greed, but by ideals or pushed by exile. It is in this crucible that Garibaldi’s Italian Legion takes up arms.Wikipédia

The Legion, far from being a professional force, gathers a brotherhood of men with broken paths: artisans, sailors, poets, fugitives, freed slaves. Among them, Andrés Aguiar, now emancipated, stands out not only for his impressive stature but for his understanding of the terrain and acute tactical sense. He is not an ordinary soldier; he quickly becomes a pillar. Where others hesitate, he advances, stoic. He is noticed. And more than that, he is respected.

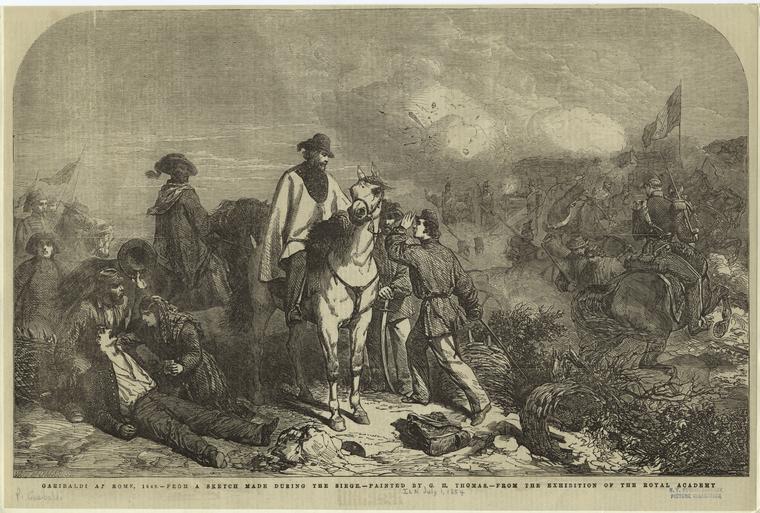

The Battle of San Antonio in 1846 is his moment of brilliance. On the banks of the arroyo of the same name, Garibaldi and his men confront Oribist troops. The clash is violent, disordered, and the enemy cavalry descends upon the republican lines. Garibaldi, fallen from his horse amid the chaos, is on the verge of capture. Aguiar, in a gesture reminiscent of an epic, emerges. He cuts through the melee, unhorses two assailants with a single lance strike, extracts his commander, and hoists him onto his own mount before disappearing into the dust.

This is not the first time he saves Garibaldi; nor will it be the last. That day, however, a new relationship is forged. Aguiar will no longer be just another soldier. He becomes the general’s shadow, his designated bodyguard, his companion on the road and in war. The bond transcends the military framework. Aguiar becomes a confidant, a brother-in-arms in a world where fraternity is not proclaimed, it is proven.

The press, already eager for heroic figures, begins to take interest in this silent but central Black soldier. His image intrigues, stands out. A giant with dark skin, mounted on a black horse, draped in a scarlet cloak, a lance adorned with a red pennant on his back. At his feet, often, a three-legged dog: Guerrillo, another survivor of the battle, whom Aguiar adopts and who will follow the two men to Europe. An improbable trio, almost legendary, that will soon become a symbol.

If war is a theater, Aguiar forges a rare role: that of the discreet equal. In a world shaped by racial hierarchies, he is one of the few Black men to operate closely with a white military leader of international stature. And yet, he never seeks the spotlight. Perhaps this is what makes his loyalty even more striking: it is not calculated, it is chosen.

San Antonio is not just a military episode. It is the moment when the fate of a former South American slave intertwines indissociably with that of an Italian revolutionary, in an improbable but indestructible alliance; born in fire and sealed in the dust of battles.

Heading to Europe: The Dream of Freedom

The year 1848 is a political earthquake for Europe: peoples rise up, empires falter, barricades rise in Paris, Berlin, Vienna… and Rome ignites in turn. For Garibaldi, it’s time to return: he leaves the banks of the Río de la Plata to join his burning native Italy. Alongside him, Andrés Aguiar embarks without hesitation. It is no longer just the war of a general he follows, it’s an idea: that of a borderless freedom, emancipated from continents and skin colors.

Upon their arrival, Italy is fragmented: Austrian troops in the north, the Bourbons in the south, and the Papal States in full upheaval. Garibaldi joins the fights in Lombardy, leading lightning actions in the cities of Luino and Morazzone. Aguiar, now seasoned and a fine strategist, plays a tactical role often ignored by European accounts: scout, liaison rider, close protector. He does not speak Italian, but he understands the logic of the terrain, the mechanics of sieges, and above all, the instinct for survival. It is his actions, his presence, his silent authority that make him a natural leader in the Garibaldian squads.

It is in Rome that Aguiar’s destiny is etched into history. In February 1849, the Roman Republic is proclaimed, overthrowing the Pope’s authority. Mazzini, Saffi, Armellini govern a city now threatened by French armies, dispatched to restore papal order. Garibaldi takes the lead of the popular defense. And among his men, Lieutenant Aguiar, finally officially promoted; an exceptional recognition for a former Black slave, in a Europe still bound by its prejudices

In Rome, Aguiar was no longer just a fighter. He became an icon. The European press, hungry for powerful images, seized upon his silhouette. The Illustrated London News published a striking drawing: Aguiar, bare-headed, wearing a red scarf and wielding a saber, riding behind Garibaldi through the winding streets of Trastevere. The British weekly described him as “a brave among the brave, imposing and dignified, the only Black face on the European lines.” Other engravings showed him with saber raised, carrying a torn flag, or defending a bastion with a lance bearing a red pennant. He became, despite himself, the glorified “Other”: the loyal exotic, the free African fighting alongside white heroes.

But behind these representations stood a man. A soldier with no family, no true nation to call his own, carrying within him another war: the war against oblivion. Aguiar asked for nothing, but his very presence was unsettling. It challenged the norm of a European struggle seen as exclusively white. He was living proof that liberty—won through the force of arms—was not confined to any one people or geography.

In the letters of Swiss and German volunteers fighting for the Roman Republic, one often finds astonished references to Aguiar: some described him as “the embodiment of courage,” others as a “red demon with biblical airs,” so powerful was his image. The Dutch artist Jan Koelman, who also fought as a soldier, recounted how Aguiar would throw lassos to unseat enemy riders, retrieve riderless horses, and stand guard while Garibaldi slept, using his saddle as a pillow.

These accounts wove around Aguiar a figure that was half-historical, half-mythical. But the reality was even more poignant: amid the ruins, between cannon blasts, a former slave from Uruguay held the line to defend a newborn Italian republic—alongside men who, only a few years earlier, would not have shared their bread with him.

In June 1849, as French troops prepared their final assault on Rome, Aguiar remained on the front line. In the chaos, near the Church of Santa Maria in Trastevere, he was gravely wounded, collapsing at its steps. According to witnesses, he cried out as he fell: “Long live the republics of America and Rome!” Rushed to Santa Maria della Scala, he died that same day despite the efforts of Dr. Bertani, the renowned physician of the Garibaldian volunteers.

Aguiar died as he lived: in the heart of battle, in service of an ideal greater than himself. He left behind no letters, no descendants, no fortune. Only a burning trace in the archives of history, and a few scattered sketches in which his tall, Black silhouette continues to haunt the stories of European liberty.

Trastevere, june 30, 1849: The final battle

On June 30, 1849, the cobbled streets of Trastevere no longer echoed with popular songs, but with the crash of shells and the cries of war. After weeks under siege, French troops—sent by Napoleon III to restore papal power—launched their final assault on the Roman Republic. In the southern outskirts of Rome, a handful of exhausted, starving, yet unyielding defenders held their ground against a better-equipped and more numerous enemy. Among them, a man in red—a massive figure with ebony skin—fought on, lance in hand, until the war finally struck him down.

Andrés Aguiar was struck by a shell fragment while defending a strategic position near the Church of Santa Maria in Trastevere, one of the oldest places of worship in Rome. According to several eyewitnesses, the impact was violent, hurling his body against a wall. Gravely wounded in the chest and side, he was rushed a few streets away to Santa Maria della Scala, where military doctors—including the renowned Dr. Agostino Bertani—tried to stabilize him. But the hemorrhaging was too severe, the resources too limited, and Aguiar died a few hours later in that small baroque church turned makeshift hospital.

For Garibaldi, the loss was immeasurable. The general—known for his fiery gaze and impassioned speech—had never allowed himself to show emotion. But faced with the lifeless body of his brother-in-arms, he broke. Captain Rafael Tosi’s testimony is explicit:

“It was the only time I saw his eyes fill with tears. He didn’t shout, he didn’t lash out. He stood in silence, fists clenched, tears rolling down his weathered cheeks.”

This grief was not expressed through gestures alone. In his journal, Garibaldi wrote these words:

“Yesterday, Rome counted new martyrs. America offered, with the blood of her valiant son Andrés Aguiar, a proof of love for our more beautiful, more betrayed Italy.”

But beyond personal sorrow, Aguiar’s death crystallizes a historical injustice. Here was a man born a slave in Montevideo, who died for a European Republic, and whose name—unlike so many other heroes of Italian unification—would appear on no statue, no public square, no schoolbook; at least, not for over a century.

His death, however, left a lasting impression. Even conservative newspapers, which had previously mocked his presence alongside Garibaldi, now saw in him a symbol. Engravings depicted him lying on the ground, bare-chested, his broken spear at his feet. He was described as “the embodiment of a foreign Black freedom, fallen for a homeland that was not his own, but whose cause he had embraced.” The tragic irony was plain to see: Aguiar died for a republic whose language he did not even speak, yet whose deeper meaning he understood better than many of his contemporaries.

The Trastevere district, where he fell, would retain little trace of his passage. And yet, soldiers, volunteers, and residents remembered. It is said that an unusual silence descended on the combat zone that evening. A tacit truce, as if even the cannons acknowledged the magnitude of the loss. Some French soldiers, witnesses to the scene, reportedly lowered their rifles upon seeing him fall.

But History chooses its heroes. And often, it forgets those who had neither famous names, nor white skin, nor bourgeois status. It is in this void that Aguiar is lost; in that moment when popular tribute is not enough to etch memory into stone.

Oblivion and resurgence: A memory reclaimed

At his death, Andrés Aguiar was mourned by Garibaldi, admired by his fellow fighters, even saluted by his enemies — yet barely mentioned in the official accounts of the nascent Italian Republic. Like so many other Afro-descendant heroes, his memory slowly faded, slipping into the shadow of a History written by others, for others.

No mention in school textbooks, no presence in patriotic speeches. On the Janiculum Hill, a sacred site of Garibaldian remembrance in Rome, marble busts watch over the city, immortalizing the faces of those who fell for Italian unification. Aguiar was not among them. Yet he had fought as a lieutenant, spilled his blood on the same soil, and had been celebrated in his time by European newspapers. But his Black skin, servile origin, and foreign status gradually excluded him from the national legend.

It took more than a century and a half for his figure to reappear in the landscape of memory. In 2013, Uruguay took the first initiative. The National Historical Museum of Montevideo held an exhibition dedicated to this forgotten son of the Republic. A commemorative stamp was issued in his honor, showing Aguiar in a red uniform, spear in hand, gaze proud — a rare image of a Black man honored not for his suffering, but for his courage.

Far from being anecdotal, this gesture marked a turning point. It re-inscribed Aguiar into Afro-Uruguayan history, where he stands as one of the first examples of transatlantic Black resilience and heroism. He became a symbol for young Afro-descendant generations in Latin America: a man born enslaved, who became a soldier, a companion of Garibaldi, and a hero across two continents.

In Italy, recognition was slower, but the global resonance of contemporary struggles eventually awakened awareness. In 2021, during a joint tribute to General Thomas-Alexandre Dumas (the French “Black general”), the city of Rome launched a memory-sharing initiative between France, Italy, and Uruguay. The mayors of Paris’s 17th arrondissement and of Rome laid the groundwork for a collaboration to carve in stone the names of those history had left on the margins.

It was only in 2024 that true justice was done. A bust of Andrés Aguiar was unveiled on the Janiculum Hill, at the heart of the Pantheon of Risorgimento heroes. Sculpted in dark stone with deep veins, it stands in stark contrast to the light marble of the other figures. A contrast that, far from diminishing him, highlights the uniqueness of his destiny and the depth of his commitment. He is no longer just a Black soldier alongside Garibaldi. He becomes what he always should have been: a symbol of transnational freedom, republican solidarity, and the universality of struggles against oppression.

The words engraved on the plaque are simple:

“Andrés Aguiar, lieutenant of the Roman Republic. Born enslaved, died free.”

A call to order for those who might still believe History is a white monopoly. A monument to remind us that the blood spilled for freedom knows no color — but that forgetting has long been selective.

The echo of a black rider in white history

The story of Andrés Aguiar is that of a free man born in bondage. It spans two continents, two revolutions, two memories. It is the story of a man whose body bore the scars of a century of oppression, and whose soul was ignited by republican ideals. His powerful figure, his red spear, his loyalty to Garibaldi, his death on the cobblestones of Rome — everything about him speaks to both classical tragedy and modern epic.

But if his name took so long to cross the threshold into posterity, it is precisely because he was Black. Because he came from the South. Because he embodied a memory that unsettles: that of a people too often pushed to the margins of the national narrative, even as they wrote its most stirring pages.

To resurrect Aguiar today is not to add an exotic figure to the republican pantheon. It is to correct a historical injustice, to restore a voice, a presence, a flame. It is to remind the world that freedom is not a Western privilege, but a universal struggle — and that those who carried it to the ultimate sacrifice deserve more than a bust or a stamp: they deserve a chapter.

Andrés Aguiar was one of them.

And now, thanks to a memory reclaimed, he no longer gallops alone into oblivion.

Notes and References

- La Guerra Grande (1838–1851) refers to the long Uruguayan civil war between the Blancos (conservatives) and Colorados (liberals), with foreign intervention by Argentina (Rosas) and Brazil, reflecting power struggles in the Río de la Plata region.

- Giuseppe Garibaldi (1807–1882) was a central figure in the Italian Risorgimento. An adventurer and military strategist, he also led campaigns in Latin America, notably in Uruguay, where he fought in the Guerra Grande with the Colorados. Known as the “Hero of the Two Worlds.”

- The Italian Legion refers to a volunteer corps founded in Montevideo in 1843 by Garibaldi during the Guerra Grande. It consisted mainly of exiled Italian republicans and carbonari, and served as a training ground for future Risorgimento fighters.

- The Battle of San Antonio (1846), during the Guerra Grande, pitted Montevideo loyalist troops—including Garibaldi’s Italian Legion—against the rural Blanco forces. Afro-descendant and foreign fighters like Aguiar played key roles in defending the besieged capital.

- Luino and Morazzone are towns in Lombardy, northern Italy. Known for their republican support in the 19th century, they were key in Garibaldi’s campaigns, bridging European and South American republican struggles.

- Santa Maria in Trastevere is one of the oldest churches in Rome, located in the working-class Trastevere district. In 1849, it was the site of fierce fighting between French troops and defenders of the Roman Republic, including Afro-descendants like Aguiar.

- Santa Maria della Scala is a historic church near Santa Maria in Trastevere. In the summer of 1849, it served as an emergency hospital for wounded Garibaldian fighters, including Aguiar.

- Agostino Bertani (1812–1886) was an Italian physician and patriot, key figure in the Risorgimento. He organized medical services for Garibaldi’s troops and embodied the union of medicine, politics, and revolutionary ideals.

Table of Contents

- Montevideo, 1810: Born in Chains

- Uruguay at War: Baptism by Fire

- Heading to Europe: The Dream of Freedom

- Trastevere, June 30, 1849: The Final Battle

- Oblivion and Resurgence: A Memory Reclaimed

- The Echo of a Black Horseman in White History