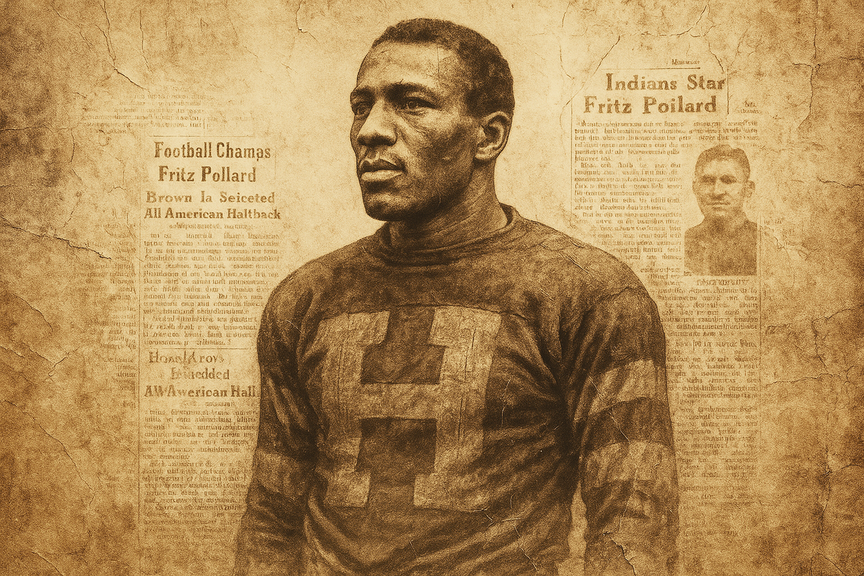

First African American coach in the NFL, Fritz Pollard was a pioneer of professional sports and a builder of freedom in the face of segregation. Behind his achievements lies a forgotten journey—one that today questions our relationship with memory, injustice, and the erased figures of American history.

Fritz Pollard, the first Black coach: forgotten victory, rediscovered memory

The icy wind lashes faces in a small stadium in the Midwest. On the uneven field, shouts ring out, a murmur rises from the sparse bleachers. In the fall of 1920, a young Black man—slender but determined—clutches the leather ball to his chest and charges forward, dodging tackles like a fish in water. Each of his steps feels like a living provocation in a society that would prefer him invisible. That player is Fritz Pollard, the first African American to dominate the fields of an emerging sport: professional football.

At the time, his talent is an offense. His mere presence, a challenge. Few can imagine that this man—often insulted, sometimes assaulted—will, just months later, become the first Black head coach in the National Football League.

What remains today of the Black pioneers of American sports? What do they teach us about tenacity, orchestrated erasure, and the slow, painful quest for recognition? Through the meteoric (and long-forgotten) rise of Fritz Pollard, we glimpse the eternal struggle to inscribe one’s own story in a book others believed they could write alone.

From segregated Chicago to ivory fields

Born in 1894 in a working-class neighborhood of Chicago, Fritz Pollard grew up in an America marked by institutional segregation. His father, John W. Pollard, a former Union soldier in the Civil War, represented a generation of African Americans for whom freedom was a fragile achievement, often betrayed by social reality. The Pollard family, modest but resilient, instilled in Fritz an unwavering belief in hard work and excellence.

At Lane Tech High School¹—one of the few public schools in Chicago that admitted Black students—Fritz quickly stood out as an exceptional athlete. Baseball, track, football: no sport resisted him. Yet behind every victory lurked constant humiliation: locker rooms denied, scornful stares, anonymous insults from the stands. It wasn’t just opponents he had to beat, but an entire system.

His admission to Brown University², a prestigious Ivy League school in New England, was almost an anomaly for a Black young man at that time. He studied chemistry, but it was on the football field that he made a name for himself. In 1915 and 1916, he propelled the Brown Bears to the top, including an appearance in the legendary Rose Bowl. His speed, agility, and ability to outmaneuver stunned defenders impressed even the skeptics. Walter Camp, the “father of American football,” described him as “one of the greatest runners these eyes have ever seen.”

In 1916, he became the first African American named to the All-America team, the national selection of top collegiate players. A resounding honor—but one that did not erase the truth: some teams refused to play against Brown if Pollard was on the field. Sometimes he had to enter the field under escort, amidst boos.

With each run, Fritz Pollard seemed to carry more than the ball—he carried the hopes of a generation too often pushed to the margins. His journey through white collegiate America opened cracks but also revealed how far there was still to go.

The player turned strategist

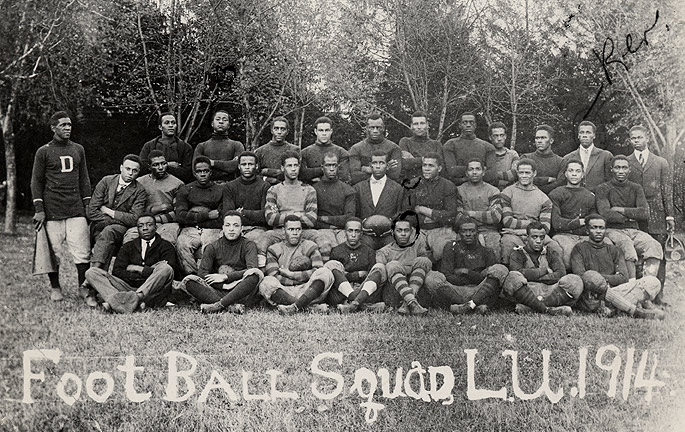

After graduating from Brown, with World War I still shaking the world, Fritz Pollard entered a barely nascent professional football league—one that was almost entirely white. In 1920, he joined the Akron Pros³, in what would soon become the National Football League (NFL). He wasn’t just an exceptional player—he was a living anomaly in a league governed by the unwritten codes of segregation.

In Akron, Pollard electrified the crowd. Fast, unpredictable, he seemed to dance across the field, evading defenders like a shadow. During the league’s inaugural season, he led his team to the very first championship title in NFL history. Such a triumph should have engraved his name in stone. But in 1920s America, a Black man’s victories were only half-celebrated.

The next year, in 1921, Pollard broke another barrier: he became the first African American head coach of a professional football team, the Akron Pros. His dual role (player and coach) unsettled a league that tolerated him on the field but resisted giving him authority. Some of his own players refused to take orders from a “colored,” forcing Pollard to coach from the sidelines, often without official recognition.

His professional career took him to several teams: the Milwaukee Badgers, Hammond Pros, Providence Steam Rollers… Everywhere, he had to balance sporting excellence with daily indignities. In Milwaukee, he played alongside Paul Robeson, another Black giant of the era, in legendary matches against Jim Thorpe and the Oorang Indians. But the pressure grew: behind the scenes, white owners began conspiring to “cleanse” the league of its Black players.

In 1926, under barely veiled pressure, the NFL unofficially closed its doors to African Americans. Pollard, his Black peers, and their dreams were abruptly sidelined—no official statement, no remorse.

Rather than collapse, Fritz Pollard chose another path: creation. Instead of vanishing, he prepared to build, to invent new playing fields for those barred from existing ones.

The brown bombers experiment

Shut out of official leagues but not ambition, Fritz Pollard refused to be erased. In 1930s America, amid the Great Depression, he reinvented himself as a builder. He created several independent teams composed exclusively of Black players, challenging the racial order imposed by dominant sports circuits.

The most famous of these was the Brown Bombers, founded in New York. The name was no coincidence—it evoked the unstoppable force, the unpredictable energy, and the Black pride embodied by boxer Joe Louis, also known as the “Brown Bomber.” Through his teams, Pollard offered more than just football games: he built spaces for affirmation, where Black talent could thrive away from the contempt of white leagues.

Under his leadership, the Brown Bombers toured the country, facing off against other Black teams and occasionally white teams willing to risk the encounter. The tours were grueling, the roads dangerous: they had to dodge hotels that denied Black guests, improvise locker rooms in warehouses, play before sometimes hostile crowds. But on the field, Pollard and his men delivered an unmatched show—each touchdown a reminder that segregation could neither silence talent nor extinguish pride.

The experiment was short-lived: the Great Depression⁴ and later the upheaval of World War II weakened independent leagues. But Pollard’s initiative left a mark—a radical refusal to disappear, a collective assertion that exclusion would not lead to invisibility.

In an America struggling to integrate its minorities into the national narrative, Fritz Pollard pioneered a different way to exist in the public space: through excellence, autonomous creation, and the memory of struggle.

The twilight of a black star

As the years passed, the spotlight moved away from Fritz Pollard. The NFL, now fully institutionalized, maintained its unofficial exclusion of Black players, while the already fragile independent teams crumbled under economic pressure. The field that had been his kingdom slipped away. Yet Pollard refused to be silenced.

In the 1930s, he launched new ventures, always with the same ambition: to exist through creation. In New York, he founded the New York Independent News, one of the city’s first African American tabloids. In its pages, he denounced racial discrimination, defended civil rights, and gave voice to the marginalized. At its peak, the newspaper reached nearly 35,000 weekly copies—a remarkable figure for a Black media outlet in a fractured America.

At the same time, Pollard diversified his activities: talent agent, tax consultant, music and film producer. He even produced Rockin’ the Blues in 1956, showcasing rising rhythm and blues stars. Always, the goal remained the same: to create spaces where Black expression was free and valued.

But behind these quiet successes, one reality stood out: in the national narrative, Fritz Pollard gradually vanished. New generations of athletes didn’t know his name. The NFL, which he helped build, failed to honor his legacy. His exclusion wasn’t repaired—it was normalized, like so many other silences in history.

When he died in 1986, Fritz Pollard left behind the legacy of a star that shone brightly but was dimmed, an exemplary life too often eclipsed by official memory.

Sources

- John M. Carroll, Fritz Pollard: Pioneer in Racial Advancement, University of Illinois Press, 1998.

- David Maraniss, Path Lit by Lightning: The Life of Jim Thorpe, Simon & Schuster, 2022. (For NFL context and treatment of racialized players)

- Charles K. Ross, Outside the Lines: African Americans and the Integration of the National Football League, NYU Press, 1999.

- Alan M. Klein, Growing the Game: The Globalization of Major League Baseball, Yale University Press, 2006. (Comparative insights on racial memory in American sports)

- Patrick B. Miller & David K. Wiggins (eds.), Sport and the Color Line: Black Athletes and Race Relations in Twentieth-Century America, Routledge, 2004.

- William C. Rhoden, Forty Million Dollar Slaves: The Rise, Fall, and Redemption of the Black Athlete, Crown, 2006.

- Pro Football Hall of Fame Archives (official dossier on Fritz Pollard)

- Brown University Archives (official biography of Fritz Pollard)

Notes

- Lane Tech (Lane Technical College Prep High School), founded in 1908 in Chicago, is one of the largest public high schools in the U.S. It was among the first to offer technical curricula to African American students during a time of widespread racial segregation.

- Brown University, founded in 1764 in Providence (Rhode Island), is one of the oldest universities in the U.S. A member of the Ivy League, it was known for relative openness to diversity in the 19th century, though discriminatory practices persisted.

- The Akron Pros were one of the founding teams of the American Professional Football Association (APFA), later renamed the NFL. Based in Akron, Ohio, they won the first professional football championship in 1920, with Pollard as a central figure.

- The Great Depression, triggered by the 1929 stock market crash, caused a global economic crisis. In the U.S., it led to widespread business failures, the collapse of independent sports leagues, and increased racial inequalities in economic and cultural opportunities.