It is often believed that slavery was abolished by decree. But in Martinique, it was the enslaved people themselves who brought it down. On May 22, 1848, following the arrest of a drummer named Romain, the island erupted in insurrection. Less than 24 hours later, the Republic was forced to declare an immediate abolition. This is the story of a revolt too often erased from official narratives.

The spark in the cane fields: A drum, a man, a people

Saint-Pierre, may 22, 1848.

Romain, an enslaved man from the Duchamp plantation, is arrested for playing the drum. A gesture that might seem trivial at first. But in the slave colonies, the drum is never neutral. It is a forbidden instrument—feared, heavy with memory. It is not merely sound; it is signal. Rhythm speaks. It organizes, warns, awakens.

Under colonial law, drumming borders on the crime of insurrection. And that day, the beat becomes a wave.

Because this is a Martinique suspended between two worlds, filled with rumors and tension. Since April 27¹, it has been whispered that Paris has abolished slavery. But no decree has arrived. Nothing has been enacted. And the enslaved people, well-versed in the betrayals of history, remember: back in 1794, freedom was promised to them—and then taken away.

Romain’s arrest is seen as a provocation, one humiliation too many. But above all: a warning. If an enslaved person can still be imprisoned for making the drum speak, then freedom is a lie.

In the hours that follow, his fellow captives grow restless. Rumors spread faster than official messengers: “He’s been locked up,” “It’s an injustice,” “They want to take back what they promised.” Silence is no longer bearable.

And Saint-Pierre catches fire.

These are not empty cries. They are cries of ending. An end to silence. An end to fear. An end to waiting.

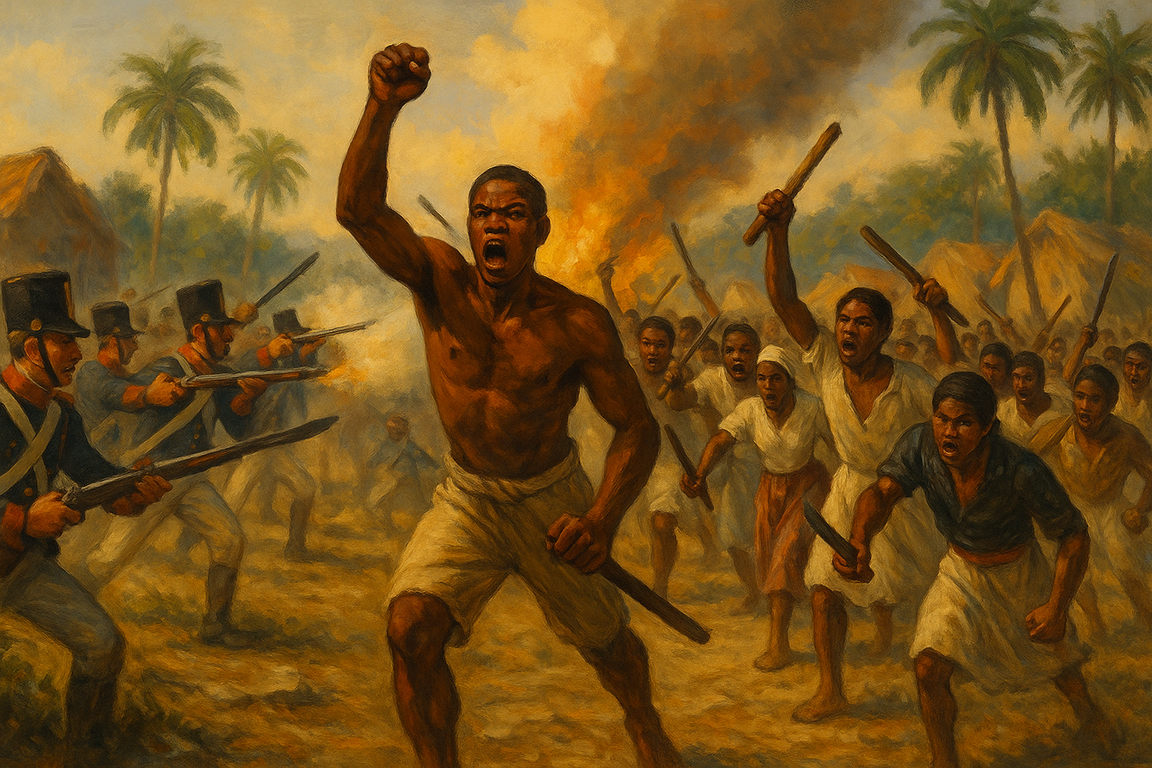

Workshops rise in revolt. Columns of Black people leave the plantations. Huts are smoking. Grand estates are under attack. Some whites flee, others resist. The enslaved seize what has always been denied them: speech, dignity, immediate justice.

The uprising spreads like wildfire. Romain’s drum has become an alarm bell. It no longer signals a secret gathering. It calls to history. It says:

“We will no longer wait to be free. We are free already.”

What Romain ignites is not a mere episode of rage. It is a reversal of sovereignty. The Republic has not yet freed the enslaved. It is the enslaved who are liberating the Republic from its own hypocrisy.

Pory-Papy and the Liberation of Romain

In the hours following Romain’s arrest, as the city of Saint-Pierre trembles, one man rises against the colonial reflexes. Pierre-Marie Pory-Papy, a mixed-race jurist and deputy mayor, chooses rupture. Where others hesitate, delay, or wait for orders from Paris or the governor, he acts.

He orders Romain’s release.

This seemingly administrative gesture is in fact a political act of enormous weight. By making this decision against the will of the sitting mayor, Pory-Papy is not merely calming a crowd: he is recognizing the legitimacy of a rebellion. He acknowledges that the drum is not a crime. Implicitly, he is saying: this uprising has its reasons, its rights, its dignity.

One must understand the power of this act in a slave society where even speaking, protesting, or gathering can be punishable by death. In freeing Romain, Pory-Papy is not just protecting a man—he is triggering a chain of political recognition. It is not Schœlcher’s decree the enslaved see enacted that day; it is a courageous local act, at street level, at human scale.

Because the history of abolition is never written from above. It unfolds in the margins, in the look of a civil servant who refuses to become the arm of injustice. In that sense, Pory-Papy represents a rare figure in colonial history: the insider who chooses the people, not the order.

This liberation becomes the tipping point of the uprising. It strips the local administration of its façade of legitimacy. It affirms that from now on, colonial authority stands naked. And that the law, if it wants to survive, must now chase the momentum of the streets.

In the history of Martinique, Pory-Papy is often relegated to a footnote. But his gesture reminds us of a fundamental truth: sometimes it is local decisions, made in the heat of the moment, that shake the pillars of power.

May 23: When republican order yields to black insurrection

Saint-Pierre, Morning of May 23, 1848.

The city no longer belongs to the authorities. It belongs to those who, just yesterday, had no names in the civil registries. The enslaved, now insurgents, control the streets, neighborhoods, workshops. Armed with machetes, sticks, and torches, they no longer demand freedom. They impose it.

Colonial estates are stormed. Some are burned, others looted. Violent clashes erupt between revolting slaves and white militias. Blood is shed, but it no longer erases the chains: it replaces them. Saint-Pierre becomes the epicenter of a total subversion. Fear changes sides.

Faced with this widespread uprising, institutional order falters. The municipal council, mostly composed of white elites, convenes an emergency session. The dilemma is clear: accept abolition, or risk total collapse of colonial power. This is no longer a matter of abstract legislation, but of survival.

That afternoon, a motion for the immediate abolition of slavery is passed. Governor Rostolan, in office for only a few weeks, has no choice: he ratifies the decision.

History may remember that slavery was abolished on April 27, 1848, by republican decree.

But the truth in Martinique tells a different story:

It was not a piece of paper from Paris that broke the chains.

It was the fire, the drum, and the cries of those who would wait no longer to be freed.

The law did not precede the revolt: it followed it.

This May 23 marks a complete reversal of the colonial paradigm. Emancipation was seized, not granted. And this inversion of the narrative is essential: it restores the enslaved as political subjects, not mere objects of a distant decree.

The Republic, caught off guard, had no choice but to ratify what the insurgents had already claimed.

A Bottom-Up abolition, a lesson for today

May 22, 1848 is not just a date in Martinique’s calendar.

It is an act. A rupture. A revolt against waiting, against silence, against legislative lies. It is the moment when an enslaved population stopped asking—and began deciding.

Because History doesn’t always happen in gilded salons or jurists’ libraries.

It is forged in burning fields, cramped workshops, collapsed huts. It sometimes begins with an arrest, a drumbeat, a refusal. It is made of tiny gestures that become epics.

On May 22, the enslaved people of Martinique did not wait to be freed: they liberated their own reality.

The law had promised them something—then betrayed it.

So they outran the law. They turned the violence of the institution against itself.

And they forced History to write their names.

To commemorate May 22 is not merely to rekindle memory.

It is to reject the official version in which the Republic magnanimously “grants” freedom.

It is to remind us that justice does not always descend from above.

Sometimes, it rises from below—from those thought silenced, broken, resigned.

This is the lesson for today. In a world where rights often retreat faster than they advance, May 22 reminds us of a subversive truth:

Legitimacy does not come from authority—

It is insubordination that founds the most essential rights.

And as long as this memory lives, the chains will never fully close again.

Sources

Frédéric Régent, La France et ses esclaves, Grasset, 2007.

Footnotes

¹ Decree of Abolition, April 27, 1848: A decree voted in Paris and signed by Victor Schœlcher, officially declaring the end of slavery in French colonies, with a grace period of up to two months for implementation. ↩︎

Summary

- The Spark in the Cane Fields: A Drum, a Man, a People

- Pory-Papy and the Liberation of Romain

- May 23: When Republican Order Yields to Black Insurrection

- A Bottom-Up Abolition, a Lesson for Today

- Sources

- Footnotes