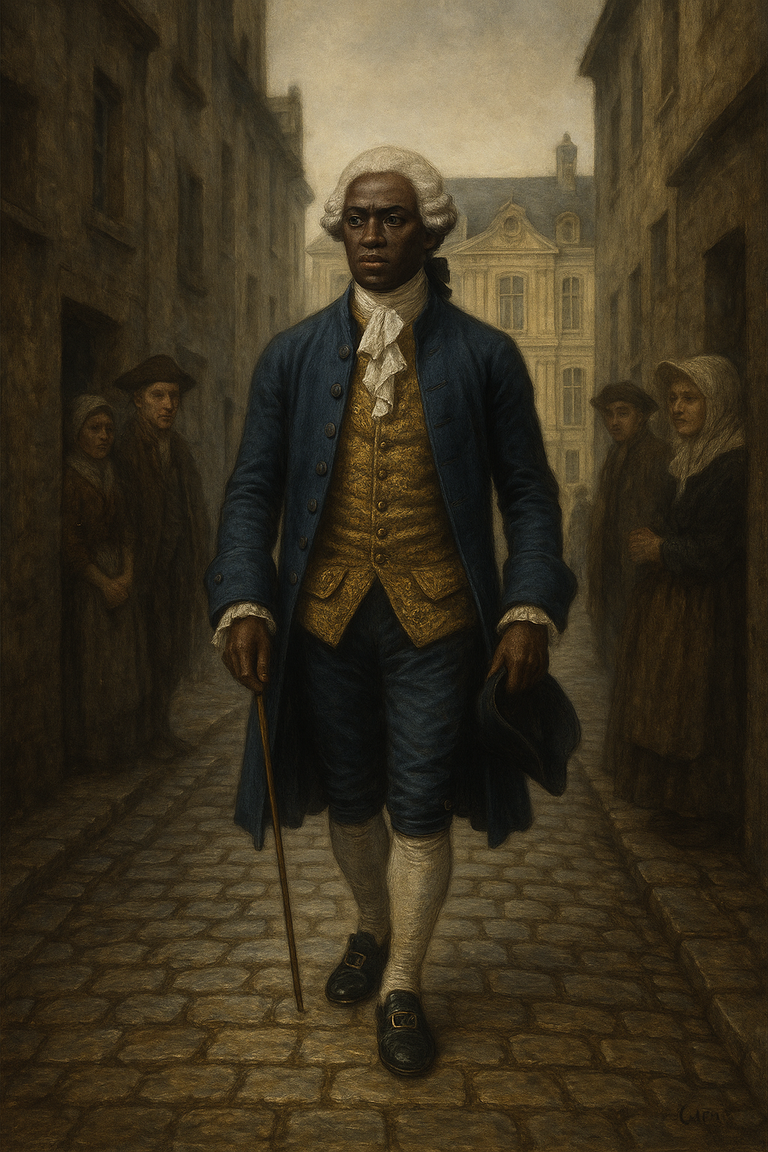

In 18th-century France, at the height of the slave era, Jean-Baptiste Médor, a formerly enslaved Black man from Saint-Domingue, became a dance master in Caen. Teaching the art of the minuet to the Norman elite, managing noble lands, and composing ballets, he embodies a remarkable trajectory. Through his life, a forgotten chapter of Afro-French history re-emerges—one marked by ascent, social ambiguity, and erased memory.

A black figure in the salons of Caen

He taught the minuet in noble households. He choreographed performances for costume balls. And he rigorously managed the lands of a countess.

Jean-Baptiste Médor, a Black dance master in Caen between 1729 and 1764, is a near-forgotten figure in French history. Yet his story challenges preconceived notions about the role of people of African descent in 18th-century France.

Originally from Saint-Domingue, Médor is thought to have been brought to mainland France by the Marquis de Sorel, former governor of the colony. Once freed, he did not choose Paris or Bordeaux, but Caen—a studious and commercial city in Normandy—to pursue a prestigious profession: that of a dance master.

The role of a dance master went beyond mere choreography. It was a social code, a school of distinction. Knowing how to move, greet, and carry oneself in a salon was essential for both nobles and the bourgeoisie.

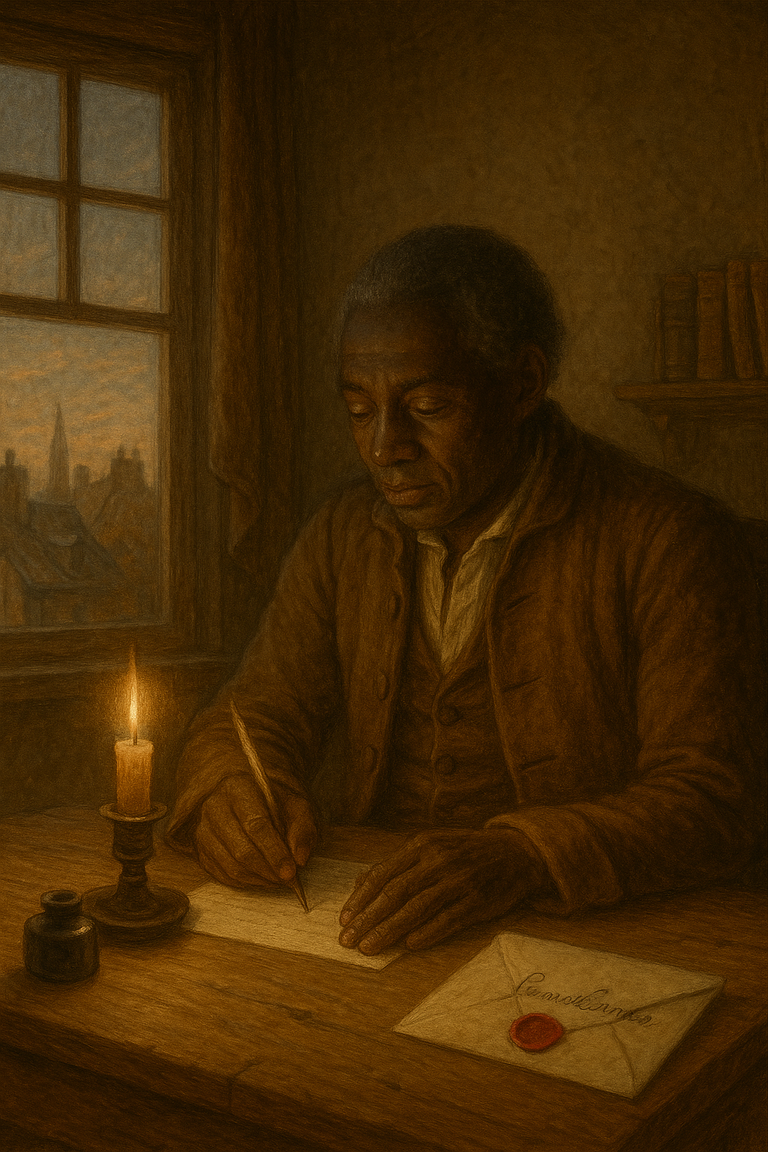

Jean-Baptiste Médor excelled in this art. He taught in well-to-do families, composed ballets for local productions, and left behind dance scores and methods now preserved in the Calvados Departmental Archives (record 2E/697). In a society still steeped in slavery, he stood out: a free, educated Black man, respected for his craft, and paid for his art.

Médor also managed the Norman estate of Marie-Catherine de Sorel, daughter of his former master, who had become Countess of Hautefeuille. From Puisaye, she entrusted him with the administration of her lands in Caen. Their correspondence, partially preserved, reveals the portrait of a respected, autonomous, and meticulous man.

But this relationship, although marked by trust, was not exempt from the racial asymmetries of the time. The countess occasionally used terms that recalled Médor’s past as a slave. And Médor, in his letters, firmly demanded fair payment and recognition of his rights.

It was in this in-between space—both integrated and assigned—that Médor moved. Emancipated, but not fully free. Competent, but never quite regarded as an equal.

This unique destiny is not isolated. In the 18th century, hundreds of people of African descent lived in mainland France—often as servants, sometimes as musicians, laborers, or craftsmen. Few left any trace. Jean-Baptiste Médor, through the documents he produced and the correspondence he maintained, emerges from the silence of history.

His example invites us to reconsider the idea of a solely white 18th century, and to shine a light on the movement, tensions, and possible paths to social mobility—given talent, networks, and sometimes luck.

Rediscovered recently through the work of the Calvados Archives and researchers specializing in the history of Afro-descendants in France, Jean-Baptiste Médor now deserves wider recognition. At a time when we are questioning colonial memory and the erasure of Black figures from national history, Médor’s story serves as a revelation.

It reminds us that Ancien Régime France was not homogenous, that African presence existed, worked, and created there. It compels us to move beyond the binary opposition between slave and master, between Africa and Europe, to explore the margins, gray zones, and exceptions.

Because sometimes, history is not written at Versailles, but in the dance halls of a provincial town. And a formerly enslaved Black man, turned dance master, can alone carry the quiet brilliance of a world far more complex than our fixed narratives suggest.

Further reading

Further reading

- Calvados Departmental Archives – Jean-Baptiste Médor Collection (record 2E/697)

- MinorHist – Research journal on minority figures

- Lecture: “Dancing in Caen under Louis XV,” Calvados Archives

Table of contents

A Black Figure in the Salons of Caen

Further Reading