He was a slave, a strategist, a republican, a governor; then a prisoner of the Republic he had served. Toussaint Louverture is not a distant icon: he is the blind spot of French universalism. This exceptional article retraces his meteoric trajectory, his betrayal by Napoleon, his orchestrated erasure, and raises the question: how can we repair the forgetting of a man who understood the Republic better than it did itself?

The legend. The silence. The erasure.

He was one of the greatest strategists of his century, a self-taught general, a political mind of rare lucidity. He was born a slave, rose through intelligence and fire, stood up to three empires; and yet, his name is only mentioned in passing, his face rarely sculpted, his work too often ignored.

Toussaint Louverture, whom Bonaparte called “the black enigma,” liberated a colony, defended a republic that was not meant for him, and ended his days in the snows of the French Jura, captive, betrayed, starved by the very France whose arms he had carried.

He was neither a dictator nor a saint. He was a black man in a white world, a free being in a century of slavery. What the Republic never forgave him for was understanding too early the founding contradiction of its principles: liberty proclaimed for all, but never conceived for Black people.

This article seeks to restore the tragic depth, tactical brilliance, and radical humanity of Toussaint Louverture. Not as a folklorized icon, but as he truly was: a political giant, a forgotten precursor of global emancipation, an inconvenient witness of French history.

Child of a colony in flames

He was born on a plantation in the former French colony of Saint-Domingue in 1743, in the belly of a system designed to crush its own. Toussaint Louverture (initially called Toussaint Bréda, after the estate where he was born) was the son of African slaves, likely from the Allada (or Arada) people of the Gulf of Guinea. His father is said to have been a prince. This changed nothing in the colonial order: on the richest island of the French Empire, a black man was nothing more than merchandise.

Saint-Domingue produced sugar, coffee, indigo, and cotton for Europe; at the cost of forced labor, mutilations, rapes, and mass killings. The average life expectancy of a slave there was under ten years. It is in this world of industrial brutality, of racist modernity, that the man who would soon challenge the Empire was born.

Toussaint was freed around the age of 33, likely for services rendered. He never attended school, but he read Rousseau, Abbé Raynal, and the Gospels with an intensity that made him a political thinker. He educated himself in secret, shaping his mind through humiliation and patience, and cultivated a rigorous Catholic faith, possibly close to Jansenism; an austere religion focused on grace, order, and duty.

He did not yet speak for his people. But already, he observed, analyzed, waited.

Before becoming a general, Toussaint was a coachman, a caretaker, and then a plantation manager. He knew horses, men, and the land. His intelligence struck people. His calm, feared authority even attracted some masters. He navigated cautiously between white colonists, African slaves, freed Creoles, and mulattoes; he spoke several languages, coded several worlds.

Far from being a romantic figure of the immediate rebel, Toussaint was a slow strategist, an absolute pragmatist. He understood that freedom is not seized through emotion, but through organization. By rising within the colonial order without betraying his people, he became the living link between the plantation and the coming war.

Toussaint remained silent. But Saint-Domingue was already beginning to burn.

The revolution in the colony

The French Revolution, with its promises of equality, fraternity, and liberty, unfolded under the eyes of millions of slaves who were not invited to the table of rights. In 1789, when the deputies of the National Constituent Assembly proclaimed the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, they did so without ever mentioning those who populated the colonies. In Saint-Domingue, the wealth of the colonists rested on inhumanity: over 500,000 slaves for 32,000 white colonists.

The debates shaking Paris quickly reached the island. The large planters demanded more autonomy to better defend their privileges. The freed people (free people of color, often wealthy, sometimes educated) demanded legal equality. But the slaves demanded nothing publicly. They listened. They remembered. They prepared.

On the estates, in the woods, in the masters’ houses, rumors circulated. There was talk of freedom, revolt, divine justice. The sermons of Abbé Raynal, the ideas of Abbé Grégoire, and Vodou prayers became invisible weapons.

On August 22, 1791, the northern plain ignited. It was the Bois-Caïman insurrection. Thousands of slaves rose. Plantations burned. Masters were killed. Symbols of the colonial order were destroyed. In a few days, the most profitable colony in the world became ungovernable.

Toussaint Louverture did not immediately participate in the uprising. He stayed aside, analyzed, observed. But this silence was strategic. He wanted to understand the balance of power, identify leaders, assess options. He was a man of war, but also a statesman in the making. When he joined the movement, it was not as a follower; it was as an organizer. He structured the troops, disciplined them, forged an army.

In 1793, the context shifted: revolutionary France, attacked on all fronts, went to war against Spain and England, who coveted the colony. White colonists were torn between royalists, republicans, and autonomists. The Republic was exhausted, isolated. It urgently sought allies.

It was at this moment that the National Convention voted to abolish slavery in all colonies on February 4, 1794, under combined pressure from Caribbean revolts and military imperatives. This decree did not stem from moral impulse: it was dictated by pragmatism.

Shortly before this decree, Toussaint, who had initially joined the Spaniards, switched sides and rallied to the French. This choice was not a betrayal; it was a realistic reading of the international context. He knew that only a European state in crisis could (temporarily) tolerate a victorious Black army.

From then on, he became a republican general. He no longer fought only to free his brothers: he became a statesman, carrying the idea that equality must have a Black face. But the Republic had not yet understood what that meant.

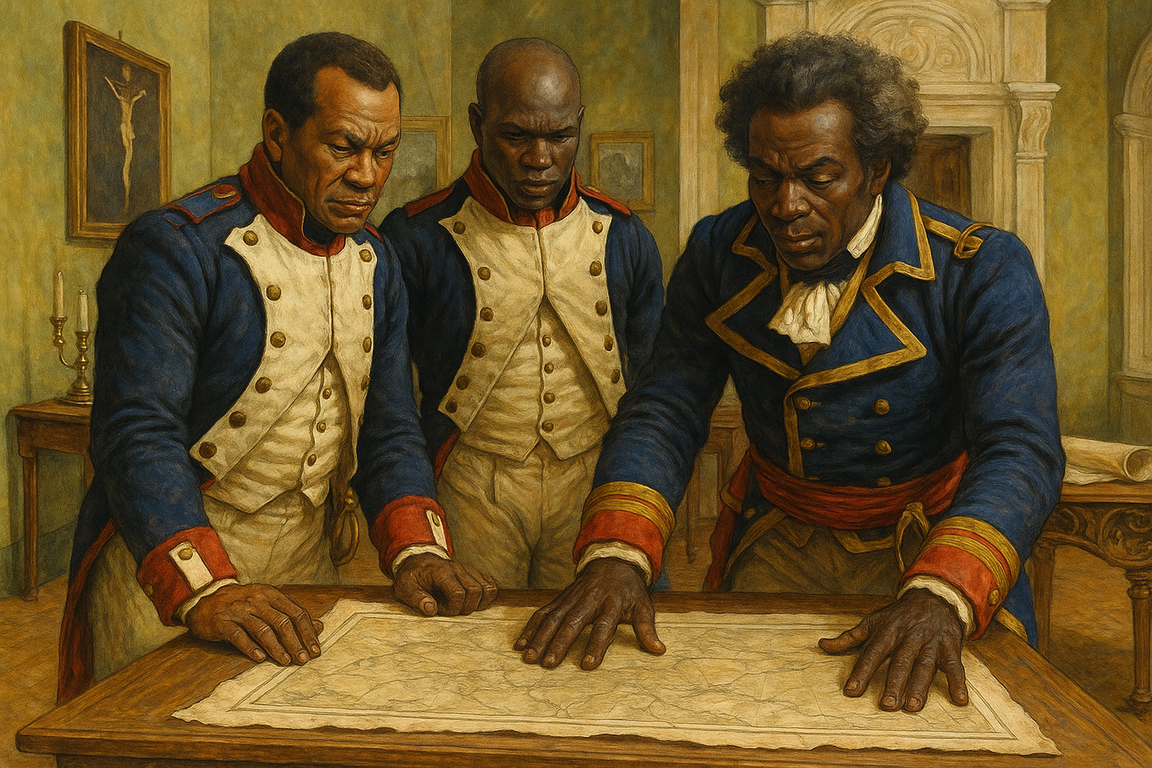

Upon his rallying to the Republic in 1794, Toussaint Louverture transformed war into a lever of power. He did not just conquer; he built. Facing Spanish and British troops seeking to seize the island, he conducted a military campaign of stunning efficiency, combining guerrilla tactics, psychological warfare, and conventional strategy.

In three years, he regained two-thirds of the territory, rallied former slaves, neutralized recalcitrant planters. With each victory, he consolidated his authority: over Blacks, freed people, colonists, and even white generals. He imposed absolute military discipline, forbade savage reprisals, maintained plantation economies—but without returning to slavery.

He understood that to save the Revolution in Saint-Domingue, it was necessary to produce, export, and keep France economically afloat. He restored the system of collective workshops: former slaves were paid but forced to remain on the land, earning him criticism… and unfair comparisons. He did not restore slavery; he attempted to prevent economic collapse.

Under his leadership, the Black army became one of the most powerful in the Atlantic. He trained it in the European manner, integrating white officers; but the structure was Black, the authority Black, the ideology Black. This was an unacceptable precedent for France, which publicly flattered him but watched with concern.

For Toussaint, ambition was no longer hidden. He appointed his own governors, dictated local laws, negotiated directly with the United States and England. He governed a French colony as a sovereign state. And he already thought beyond Napoleon.

In 1801, he crossed the breaking point: he proclaimed a Constitution for Saint-Domingue, drafted by himself. It definitively abolished slavery, guaranteed freedom of worship, prohibited racial discrimination, established full autonomy for the island while maintaining attachment to France… in theory.

But above all, this Constitution named Toussaint governor for life, with the right to choose his successor. It was too much. For Paris, for Bonaparte, for the colonial order. A Black man proclaiming himself leader of an autonomous state, legislating without the approval of the Directory, addressing foreign powers in his own name; it was a political crime.

For Toussaint, this Constitution was insurance against the return of slavery. For Napoleon, it was a disguised declaration of independence. The affront was clear, the response would be brutal.

The betrayal (the Bonapartist trap)

Toussaint Louverture, the man who shook the Empire

When Napoleon took the reins of France in 1799, he inherited a fragmented empire and a revolutionary ideology he claimed to continue while emptying it of its substance. The Consulate displayed words of equality, but secretly prepared the return of racial hierarchy. For Napoleon, the colonies had to become what they once were: instruments of wealth, where Black labor could be exploited at will.

In Saint-Domingue, the abolition of slavery (1794) had shaken the world order, weakened the slave trade networks, and inspired Black peoples across the Atlantic. Louverture now reigned as a respected strategist, self-proclaimed governor but apparently loyal to the Republic. Too free, too autonomous, he embodied an unacceptable precedent for a rebuilding empire.

In 1802, Napoleon sent 30,000 soldiers to the colony, the largest overseas expedition ever launched by France. At its head: Charles Leclerc, his brother-in-law, a cold, methodical man carrying a secret order: break Toussaint, eliminate Black generals, restore the old order, by force if necessary.

The first exchanges were ambiguous. Leclerc proclaimed peaceful intentions, praised Toussaint’s talent, thanked him for his work. But arrests began. Generals Moïse and Maurepas were eliminated. French troops reoccupied towns, disarmed Black troops. The war was conducted without declaration.

Toussaint, clear-sighted, sensed the trap. He refused provocations, withdrew, gained time. He knew his forces were weakened, that the population was weary of war. He sought a way to spare his people’s blood.

In May 1802, a fragile agreement was reached: Toussaint agreed to retire from public life, on condition that the abolition of slavery be guaranteed, the Republic respected, peace real. He returned to his Ennery plantation in the North. He ceased hostilities, but remained vigilant. He wrote, he watched, he waited.

This gesture was made out of patriotism, not naivety. He still believed in the state’s word, the spirit of the Revolution, the possible respect of law. He did not see that the France of 1802 was no longer that of 1794. He did not yet understand that for Napoleon, a Black general would always be a problem to solve; not a citizen to respect.

This compromise would cost him his freedom. Then his life.

On June 7, 1802, the trap closed. Toussaint Louverture was arrested by treachery, under the pretext of an interrogation. It was General Brunet, Leclerc’s emissary, who invited him to a discussion under the guise of conciliation. Toussaint went, still trusting the principles he had served, convinced that one could speak man to man. He would never see his home, nor his island again.

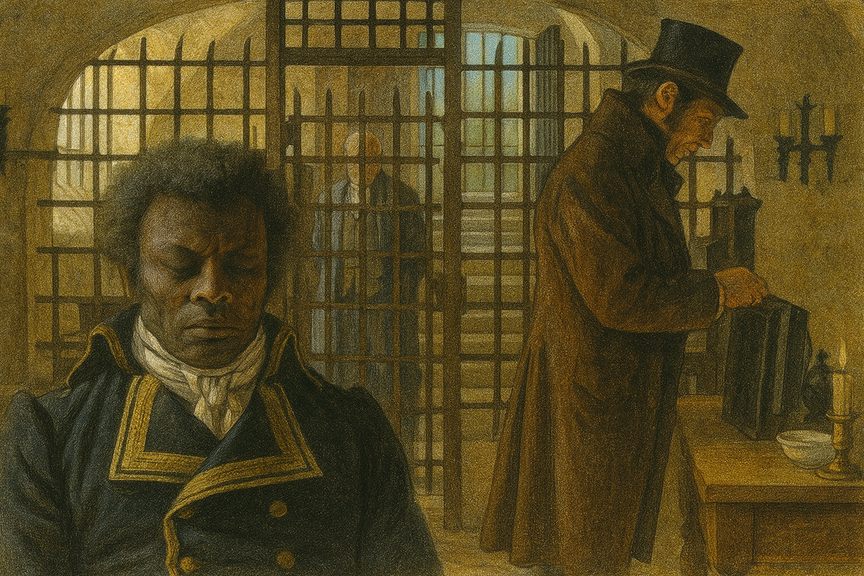

No warrant, no trial, no public statement. He was kidnapped, torn from his family, shackled with his wife Suzanne and youngest son. Napoleon wanted to silence his voice, erase his influence without making him a hero. He was immediately shipped on a military vessel to metropolitan France. But not Paris, not a court, not an honorable cell. He was sent into silence, into shadow, into organized oblivion.

His destination: Fort de Joux, in the Jura mountains. A cold, damp fortress, isolated at 1,100 meters altitude, perched in a landscape of fog and frost. Toussaint arrived in the middle of summer. He did not yet know that this place would be his unmarked tomb.

The detention conditions were inhuman. His cell was barely six square meters, with no direct light, no fire, no papers, no books. He asked for writing materials; they refused. He requested a Bible; they hesitated. He was watched day and night. As winter approached, the walls sweated moisture, the cold gnawed at him. His clothing was insufficient. Rations were reduced. He was starved. Slowly.

The Republic, which claimed to fight tyrants, had invented here a modern form of assassination: administrative disappearance. He was neither judged nor condemned. He was invisibilized slowly, eliminated behind public opinion’s back.

On April 7, 1803, Toussaint Louverture died in his cell. The official autopsy cited pneumonia worsened by malnutrition. He weighed barely 60 kilograms. No monument, no ceremony, no identified coffin. According to some accounts, his body was thrown into an icy pit, without burial, like a historical cast-off.

But what Napoleon had not foreseen was that silence sometimes nourishes anger and memory. In Haiti, news of the deportation awakened the Black generals: Dessalines, Christophe, Pétion. They took up arms, refusing to believe in colonial peace.

A few months later, the French army was defeated. On January 1, 1804, Haiti became independent. The first free Black state in the modern world. A victory born of mourning. The man they thought to silence became a founder.

Stolen memory, confiscated legend

Toussaint Louverture, the man who shook the Empire

He was one of the greatest military and political leaders of the modern world. He defeated European armies, abolished slavery by arms, governed a colony like a state. And yet, no statue in his honor was erected in France before the 21st century. No square bears his name, no street in Paris, no public holiday, no institutional recognition worthy of his work.

In school textbooks, when he is not forgotten, he is caricatured. Either as a “heavy-handed Black dictator,” or as a “good general loyal to France”—two equally false narratives, both useful to republican forgetting.

His body was never recovered. No grave, no mausoleum. As if he had never existed. The Republic erased not only his memory but his very substance. And this silence was not an accident: it was a strategy.

Because Toussaint unsettles. He did not only become a free Black man; he became a powerful Black man. And that, the official French history, still shaped by colonial repression, cannot accommodate without threatening its myths.

Toussaint Louverture never had his place in the Pantheon. And this is not forgetting; it is a choice. Because to include him would be to recognize three truths the Republic cannot bear.

First, that he embodies the hypocrisy of French universalism. The Declaration of the Rights of Man de facto excluded him. The Republic never freed him; he freed himself.

Second, that it reveals a fundamental betrayal: France proclaimed equality while nullifying it in its colonies. It sent armies to restore slavery. It let die in the cold a man it called its general.

Finally, because his victory is not French. It is Black, sovereign, popular. It did not take place in Paris, but at Vertières, at Bois-Caïman, in the fields of burning cane. It owes nothing to the Republic: it surpasses it, contradicts it, exposes it.

To pantheonize Toussaint would be to say that France owes its first imperial defeat to a slave turned general. It would be to admit that liberty is seized; it is not begged for.

Sources

Jacques de Cauna, Toussaint Louverture et l’indépendance d’Haïti: témoignages pour un bicentenaire, Karthala, Paris, 2004, 299 p. (ISBN 978‑2‑845‑86503‑7).

Philippe Girard, Ces esclaves qui ont vaincu Napoléon. Toussaint Louverture et la guerre d’indépendance haïtienne (1801‑1804), Éditions du CNRS, 2012.

Jean‑Louis Donnadieu, Toussaint Louverture, le Napoléon noir, Belin, 2014.

Frédéric Régent, La France et ses esclaves: de la colonisation aux abolitions (1620‑1848), Grasset, Paris, 2007.

Antoine‑Marie‑Thérèse Métral & Isaac Louverture, Histoire de l’expédition des Français à Saint‑Domingue, Fanjat aîné, Paris, 1825, p. 325.

Alfred Nemours, Histoire de la captivité et de la mort de Toussaint‑Louverture, Berger‑Levrault, 1929.

Contents

The Legend. The Silence. The Erasure.

Child of a Colony in Flames

The Revolution in the Colony

The Betrayal (the Bonapartist Trap)

Stolen Memory, Confiscated Legend

Sources