Contemporary accounts report the privileged nature of women’s status in the medieval West African Empire of Mali.

Ibn Battuta and the status of women in the Mali empire

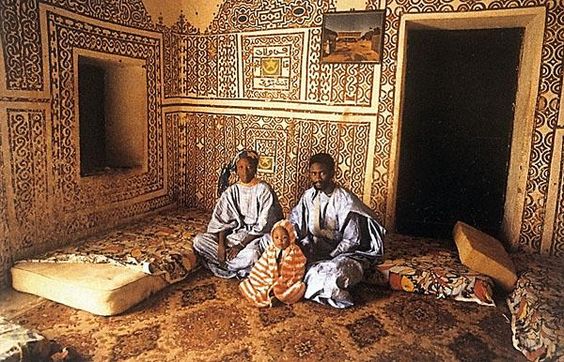

The status of women in the ancient Mali Empire is first known to us through the testimony of Ibn Battuta, the famous 14th-century Moroccan Berber traveler. In 1352, Ibn Battuta traveled from the Moroccan city of Sijilmasa to Oualata (present-day Mauritania). At the time, Oualata was the northernmost province of the Mali Empire.

The status of women in Oualata

Ibn Battuta recalls that in Oualata, “women are extremely beautiful and more important than men. The condition [of the inhabitants of Walata] is strange, and their customs are among the most eccentric. As for their men, there is no sexual jealousy among them. None of them traces his genealogy through his father, but rather through his maternal uncle. A man passes on his inheritance only to the sons of his sister, to the exclusion of his own sons. […] As for their women, they are not modest in the presence of men and do not veil themselves, despite their perseverance in the practice of prayer.”

Anyone who wishes to marry one of these women may do so, but women do not travel with their husbands, and even if they wished to do so, their family would not allow it. Women have male friends and companions outside what is permitted by the bonds of marriage [and family]. Likewise, men have female companions and friends outside what is permitted by the bonds of marriage [and family]. One of them may enter his home, find his wife with a male companion, and see no objection in it.

The matrilineality practiced in Oualata does not appear to have been in effect in the capital, as will be seen below, at least with regard to the succession of rulers.

Ibn Battuta came from a country where segregation between women and men was the norm under Sharia law. For him, it was scandalous that in a Muslim country, women could associate with men other than their husbands, brothers, or fathers.

Two anecdotes in particular deeply shocked Ibn Battuta in Oualata. He recounts them as follows:

“One day, I entered the house of a qadi (judge) in Oualata after he had given me permission to enter. I found him in the company of a young and beautiful woman. When I saw her, I was shocked and began to turn away. She laughed at me and showed little modesty. The qadi said to me: ‘Why are you leaving? She is only one of my companions.’ I was shocked by their conduct, for he had performed the pilgrimage to Mecca and belonged to the class of the faqihs (theologians).”

“One day, I entered the house of Abu Muhammad Yandakan […] It was with him that I had traveled here. I found him sitting on a mattress, and in the middle of his house there was a bed with a canopy. Sitting on it were a woman and a man who were talking together. I said to him: ‘Who is this woman?’ He said: ‘She is my wife.’ ‘Who is the man who is with her?’ He said: ‘He is her companion.’

I said to him: ‘You accept this even though you have lived in our country and have been familiar with the rules of the Sharia?’ He said: ‘The companionship between men and women is considered honorable in our country and takes place under good conditions; there is nothing suspicious about it. They are not like the women of your country.’ I was shocked by this thoughtless answer; I left him and never returned to him after that.”

It is remarkable that in Oualata, a city of the Mali Empire, the status of women was, according to Ibn Battuta, more important than that of men. While it is difficult to understand precisely what the author meant by these words, he explains that succession was matrilineal, meaning that a man’s inheritance was passed on to his sister’s sons and that his genealogy was traced through his maternal uncle.

This practice was explained by a scholar such as Cheikh Anta Diop as part of an “African matriarchy.” However, this practice should not in itself be considered proof of better treatment of women in society. This choice was based solely on the more demonstrable nature of blood ties between a man and his uterine nephew compared to his less easily demonstrable relationship with his own son.

Certainly, Ibn Battuta emphasizes the greater importance of women in society. However, one may wonder whether this greater consideration given to women was interpreted in comparison with their situation in Marinid Morocco. For example, did a man also pass on his inheritance to his sister’s daughters as he did to her sons?

One thing is certain: segregation between the sexes was absent in Oualata. A married woman could converse with a man who was not a member of her family. The logic behind segregation between men and women can be explained by a desire to prevent adulterous temptation and to avoid making women sexual objects and victims of physical and sexual violence.

This represents a deeply pessimistic view of humanity, assuming that marriage cannot be respected if unmarried people of opposite sexes spend time together.

In Mali, and in Manding history more generally, as will be seen, the low propensity for crime and injustice and the strong condemnation of adultery seem to have been deeply rooted in customs. This appears to have encouraged such interactions between people of opposite sexes without fear of violence.

Ibn Battuta and the status of women in the capital of Mali

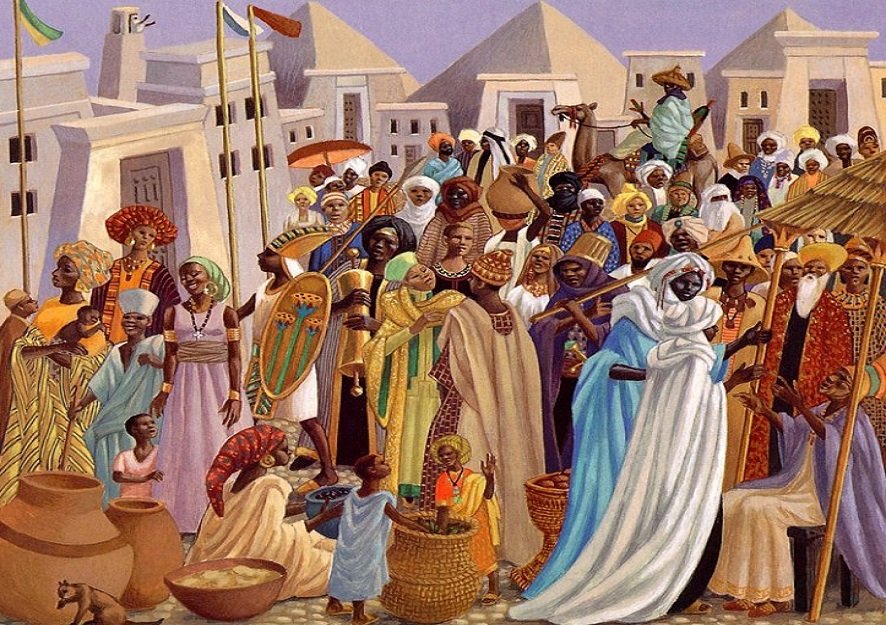

After Oualata, Ibn Battuta traveled to the capital of Mali, which remains poorly identified by historians and archaeologists today. At the time, the ruler of Mali was Mansa Sulaiman.

As mentioned earlier, among the things that impressed Ibn Battuta about the Mali Empire were the security that prevailed there and the inhabitants’ love of justice and hatred of injustice.

“Among their qualities is the small degree of injustice among them, for there is no people more distant from it. Their sultan pardons no one in any matter involving injustice. Among these qualities is also the prevalence of peace in their country; the traveler need not fear there, nor does the resident fear a thief or a robber. They do not interfere with the property of a white man who dies in their country, even if it consists of great wealth, but rather entrust it to a trustworthy person among the Whites who keeps it until the rightful claimant recovers it.”

The moral uprightness of the inhabitants of Mali and the intolerance of their ruler toward injustice must have strengthened the confidence these populations had regarding interaction with people of the opposite sex, even if they were not married or related. All of this was likely facilitated by a historical absence of segregation between the sexes among Manding populations. This is illustrated by another observation by Ibn Battuta in the capital of Mali, who reports of the ruler at the time that:

“[…] The Sultan was angry with his first wife, the daughter of his paternal uncle, who was called Qasa, which means queen among them. The queen is his partner in kingship, as is customary among the Blacks. Her name is mentioned with his on the pulpit. The sultan imprisoned the queen […] and appointed in her place his other wife, Banju. She was not among the daughters of kings. The population discussed this matter greatly and disapproved of this action.”

In Mali, therefore, royal power was shared between the Mansa and the Kaasa, a word that still means “queen” in the Malinké language. The role of Kaasa appears to have been reserved for daughters of kings, like that of Mansa. Kingship thus seems to have been shared between a king and a queen, the latter being a sovereign in her own right rather than merely the king’s wife. Her role may have been comparable to that of a queen mother, as in Meroë or Asante, where the union between the sovereign and the female ruler did not carry a sexual connotation.

This represents an important indication of male-female parity in Mali, although it remains incomplete. However, another custom reported by Ibn Battuta seems to show an imbalance in the treatment of men and women. This concerns an account of human sacrifice followed by an act of cannibalism.

“Then there came to see Mansa Sulaiman a group of those Blacks who eat human beings, accompanied by one of their amirs (commanders). […] In their land there is a gold mine. The sultan was gracious toward them. He gave them as a gift of hospitality a female slave. They killed her and ate her. They smeared their faces and hands with her blood and thanked the sultan in return. I was told that it is their custom to do this every time they come to visit him.”

This case of human sacrifice reported by Ibn Battuta, if authentic and exhaustive, is unfavorable to women. However, nothing tells us that other human sacrifices of this type did not involve men. Nevertheless, the existence, according to Soninke tradition, of the annual sacrifice of a virgin for the perpetuity of the Ghana Empire (Wagadou), the predecessor of Mali as a major regional power rich in gold, could confirm the importance of female victims in human sacrifice within the cultural area of medieval Mali and its tributaries.

The status of women among the heirs of the Mali empire

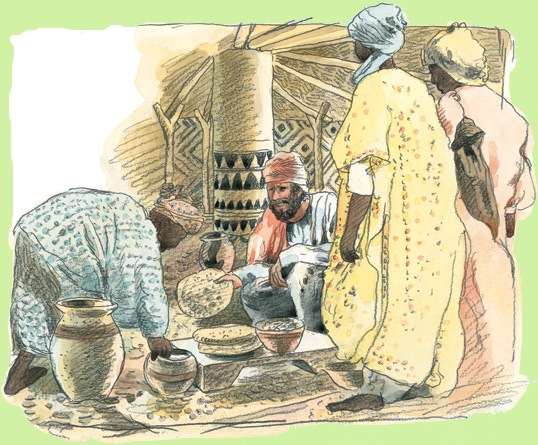

The status of women in the Mali Empire can also be reconstructed through practices recently documented among the descendants of the empire’s core population. Among these, known as the Manding peoples, are the Malinké of Guinea and Côte d’Ivoire and the Bambara of Mali. The Malian historian, ethnographer, and politician Madina Ly-Tall devoted a field study to the status of women in traditional Manding society. Published in 1978 in the renowned journal Présence Africaine, this article is based on field research in Manding regions.

The study shows the crucial importance of women in the economic sphere of society, through the practice of agriculture, craftsmanship, and the children they “provided” biologically and educated. Through the considerable work they performed, women enjoyed great respect within society, particularly from their children.

This respect often guaranteed them influence over men in society, whether their sons or their husbands. This was the case of Saran Kégni, the favored wife of Samori, who had a predominant influence on her husband’s judicial and military decisions.

As the author reports through the testimony of an informant, Koloba Camara, chief of the village of Bankoumana:

“Nothing was done without the woman; if you hear a man belittle a woman, it is in reality superficial (unless it concerns empty women, superficial women as well); nothing was done without her participation. When everyone said of a man that he was good, serious, worthy, he had to have a wife, otherwise he was considered incomplete. The woman was indeed the complement of the man. His companion in good days and bad.”

The status of women among the descendants of the Mali empire through the concept of badenya

The importance of women’s status in traditional Manding society is also perceptible through the concepts of fadenya and badenya. Fadenya means “being children of the father,” while badenya means “being children of the mother.” By extension, fadenya signifies rivalry and conflict, referring to relationships between sons of the same father but different mothers, who must compete for inheritance traditionally passed down by the father

Similarly, badenya, which refers to the relationship between children of the same mother, especially in polygamous households, expresses solidarity and the absence of rivalry among these children and with their mother. Ryan Thomas Skinner expresses the meanings of badenya in its narrow and broad senses as follows:

“Badenya, literally meaning ‘mother-child-notion,’ refers to the shared affection felt by children of the same mother in polygamous families and connotes devotion to the home, family, and tradition. As a social concept, badenya conveys a sense of community, social solidarity, and shared intimacy that is the intersubjective essence of civil society.

Fadenya can be either positive or negative. In the former case, the antisocial act must be positively reintegrated into society and contribute to the improvement of badenya. This was the case of Soundjata Keïta, founder of the Mali Empire, who, after coming into conflict with his half-brother, went into exile and eventually recovered his father’s inheritance, bringing peace, solidarity, and harmony to Mali—badenya.

Badenya is a space in which women display their greatest influence. With regard to the status of women, it is remarkable that this inherently positive notion, badenya, is associated with women. This reality likely reflects the tension created by the love a son bears for his mother within the patriarchal structure of society.

The status of women through modern manding cosmogony

Although the elite of the Mali Empire in the fifteenth century was Muslim, or at least Islamized, there is no doubt that a large portion of the population remained faithful to the local traditional religion.

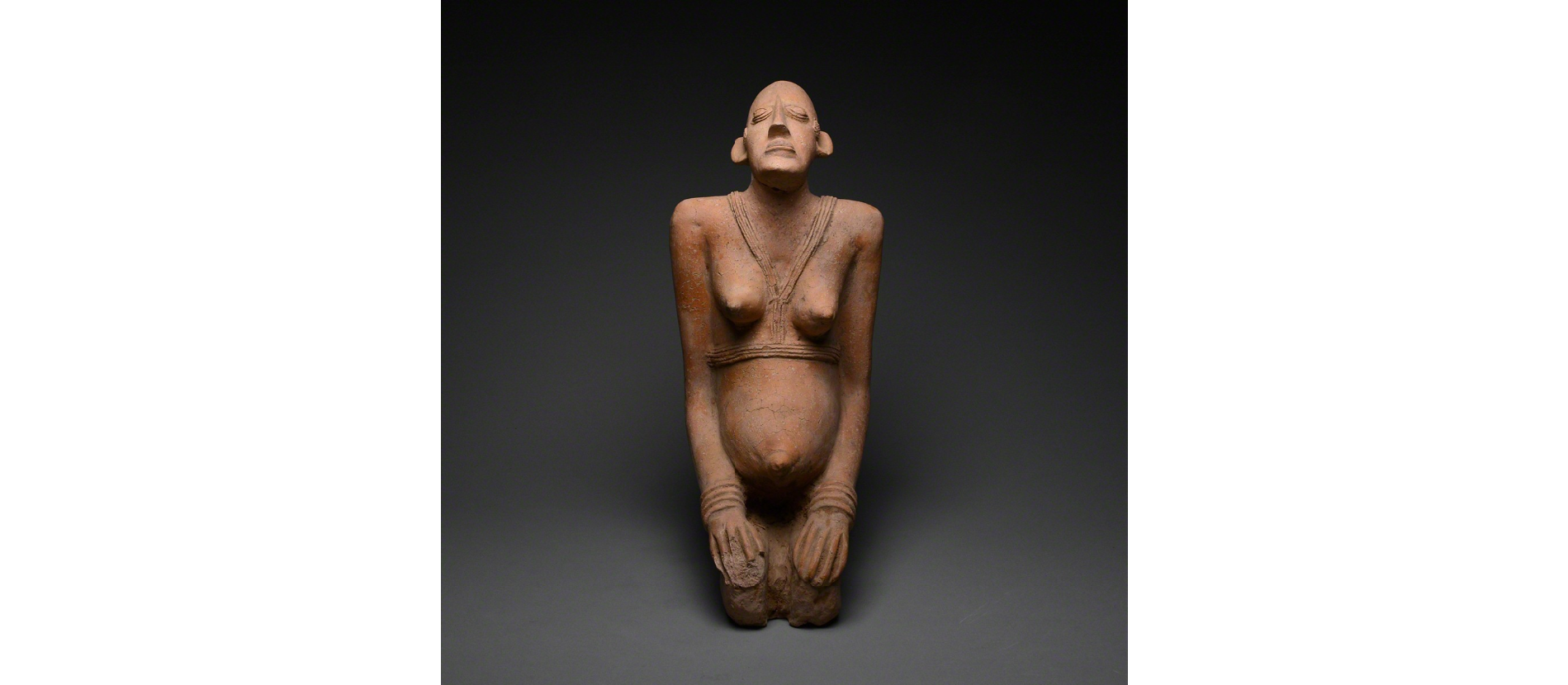

A well-known Manding myth of the origin of the world presents the first two human beings as twins, namely the woman Mousso Koroni and the man Pemba.

This myth is of particular interest for a better understanding of the status of women in traditional Manding culture.

In this narrative, it is the woman Mousso Koroni who shows disrespect toward the Supreme Being and leads her twin astray, notably through her indecent sexual behavior.

See also: The status of women in the Kingdom of Ndongo

The behaviors attributed to Mousso Koroni are often used to explain women’s behavior today.

In another version of the myth, whose account of the creation of Mousso Koroni recalls the misogyny of the biblical creation myth of Eve from Adam’s rib, Mousso Koroni is created from Pemba.

She then rebels out of jealousy toward Pemba and his sexual access to all the women he wishes to possess, and refuses to continue participating in the act of creation.

As Culianu explains:

“In the Bambara myth, Mousso Koroni is a female figure who rebels against the flawed ‘masculine’ order of the world. Her revolt can be defined in a generic sense as a quest for freedom, but it can also be interpreted in sexual terms (her betrayal of Pemba is in fact an act of adultery). The downfall of Mousso Koroni determines humanity’s transition from its original immortality and joy to a condition in which evil, misfortune, and death are irrevocably associated with the human condition. However, Mousso Koroni helps humanity in distress by teaching it language and agriculture.”

In a sense, Mousso Koroni serves as a guidebook for how a traditional Manding woman should—and should not—behave.

The dark side of the status of women in historical manding societies

As Madina Sy-Tall points out, polygamy was reserved for chiefs and very wealthy families. She adds that adultery was very poorly regarded because it could harm a family’s economic balance by failing to “provide” the children and labor force they were expected to contribute. This hostility toward adultery helps explain the casual companionship between unmarried men and women in the Mali Empire under the reign of Mansa Sulaiman, where adultery was not contemplated at all.

Still according to Madina Sy-Tall, the Manding woman was required to be submissive to her husband:

“The married woman owed total fidelity to her husband. When she joined a family, it was generally to leave it only upon her death. Even when the husband died before her, she married a younger brother of the deceased, because she had been given in marriage to the entire family and not to a specific individual.

She could hardly avoid this transfer, because she had been married with the fruits of the collective labor of all the brothers; the younger brothers, who spent their entire lives working for their elders, had no other means of marrying.

To illustrate all this, a Malinké proverb stated: ‘A woman is never married twice.’ Her bride price was paid only once. If she refused to ‘pass’ to a brother, not only did she place herself outside society, but she also had to reimburse the bride price, which would be used to marry the one she had refused.”

See also: The status of women in the Kingdom of Dahomey

The author concludes, regarding the status of women in precolonial Manding society, that women “enjoyed a great deal of consideration and respect. They were nevertheless considered inferior to men if we apply today’s criteria of evaluation; but if, on the contrary, we judge these past relations between men and women according to Malinké norms themselves, we should rather speak of complementarity between the two.”

According to her, it was the economic changes linked to colonization that disrupted this complementarity, this balance between women and men: the monetization of the economy, agriculture oriented toward industrial export products, and economic activities carried out by men during the colonial period. All these factors contributed to diminishing the status of women in Manding societies.

As we have seen, however, whether complementary to that of men or not, more advanced than in Arab countries or not, the status of women was not equal to that of men in traditional Manding society, insofar as women did not have access to certain practices such as polyandry, were technically married to an entire fraternity, were subject to their husbands, and were barred from certain domains such as trade.

That the status of women may have been more advantageous in Black African societies—Manding societies in particular—than in Eurasian societies in general should not blind us to the inequalities suffered by our female ancestors. Only recognition and serious examination of these realities by their descendants can guarantee parity in Africa’s future.

The status of women in the Mali empire: selected bibliographic references

Ibn Battuta, Samuel Hamdun, Noel King / Ibn Battuta in Black Africa

Youssouf Tata Cissé / Le sacrifice chez les Bambara et les Malinké

Cheikh Anta Diop / L’Unité Culturelle de l’Afrique Noire

Ioan Petru Culianu / Feminine versus Masculine. The Sophia Myth and the Origins of Feminism

Madina Ly / La femme dans la société traditionnelle mandingue (based on field research)

Ryan Thomas Skinner / Civil Taxis and Wild Trucks: The Dialectics of Social Space and Subjectivity in Dimanche à Bamako