Throughout Black History Month, Nofi will publish articles by the late Runoko Rashidi that explore the richness and diversity of the lives of Black people around the world, today and in the past. Today: the case of Ramses the Great!

The reclamation for the African world of the ancient Kamite heritage, which includes knowledge of heroic rulers such as Ramses the Great, must be regarded as an integral part of the Black liberation movement. He will inspire and guide us. Kmt was the heart and soul of Africa, and all we need do is look at its noble traditions, its dignity, its humanity, and its royal splendor to measure how far we have truly fallen from power.

Although it was African Sudan—the ancient “Ethiopia” (Land of the Blacks)—that gave birth to the earliest civilization, it is Kmt (ancient Egypt), the child of Ethiopia and the greatest nation of antiquity, that has been the focus of most historical research. For now at least, Kmt remains the central point of our Africa-centered research and will probably be the subject of much of our study for some time to come. Not only were the origins of ancient Egypt African, but throughout the dynastic age and during all periods of real splendor since the initial unification of Upper and Lower Egypt in the fourth millennium BCE, Black-skinned, woolly-haired men and women virtually ruled supreme.

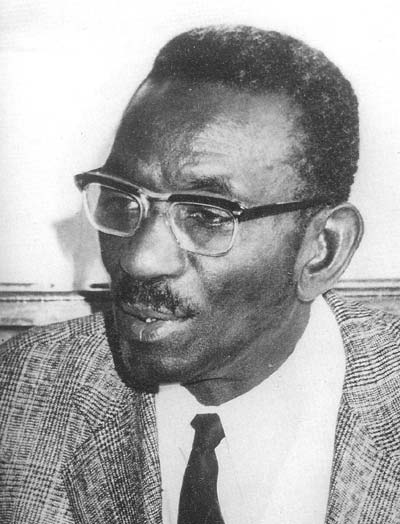

In the intense and unceasing struggle to establish and scientifically prove the African foundations of ancient Egyptian civilization, the late Senegalese scholar Cheikh Anta Diop remains one of the fiercest and most ardent champions. Diop (1923–1986) was among the greatest Egyptologists in the world and served as director of the radiocarbon laboratory of the Fundamental Institute of Black Africa in Dakar, Senegal. The range of methodologies employed by Dr. Diop in his extensive work included examination of the epidermis of royal Egyptian mummies recovered by the Auguste Ferdinand Mariette expedition to test melanin content; precise osteological measurements and meticulous studies in relevant areas of anatomy and physical anthropology; careful examination and comparison of modern blood groups in Upper Egypt and West Africa; detailed linguistic studies; analysis of the ethnic designations used by the Kamites themselves; corroboration of distinct African cultural traits; documentation of biblical testimonies and references regarding ethnicity, race, and culture; and the writings of early Greek and Roman scholars describing the physical appearance of the ancient Egyptians.

Diop firmly believed that “the high point of Egyptian history was the Nineteenth Dynasty of Ramses II.”

The sixty-seven-year reign of Ramses the Great was an era of general prosperity, stable government, and grand building projects for Kmt. Ancient deities such as Ptah, Ra, and Set were elevated to high rank. The worship of Amun was restored and his priests reinstated. Major wars were fought against the Libyans, the Hittites, and their allies. From Nubia to the Egyptian Delta, magnificent temples were hewn from bare cliffs. Splendid tombs were built, renovated, and embellished in the western hills of Waset and Abydos. The new Egyptian city of Pi-Ramses made an impressive debut.

Ramses was deified during his lifetime, and through the relentless projection of his incomparable personality, the name Ramses, son of Amun-Ra, became synonymous with kingship for centuries. Ramses II was truly great. He was the dominant figure of his age and set the models and standards by which others would rule.

As for the ethnicity of the great Ramses, Cheikh Anta Diop threw down the gauntlet without hesitation and spoke of him in language of unmistakable firmness and certainty:

“Ramses II was not leucoderm and could even less have been red-haired, for he ruled over a people who instantly massacred red-haired persons whenever they encountered them, even in the street; such people were considered strange, unhealthy beings, bearers of bad luck, and unfit for life…. Ramses II is Black. Let him sleep in his Black skin for eternity.”

Unfortunately, the mummy of Ramses II was more than disturbed. During the Twenty-First Dynasty, the mummies of Ramses II and Seti I, along with other royal mummies, were removed from their tombs and reburied in the cliffs of Deir el-Bahari. It was there that the mummies were discovered by the Department of Antiquities in 1881 and transported to Cairo.

The great king was not allowed, as Diop wished, to “sleep in his Black skin.” He was subjected to numerous modern observations and experiments. Regarding these, Ivan Van Sertima made a number of extremely fascinating observations:

“One of the things that struck me most about Diop as a person was his absolute honesty. He was never afraid to criticize something African or Black when it deserved criticism. I never found him in any equivocation or exaggeration. He told me twice, in London and in Atlanta, that the Blackness or Africanness of Ramses II was beyond doubt. He told me he had seen the mummy and that the skin of the mummy was as Black as his own. He said, however, that after it had been subjected to gamma rays, the skin had taken on a grayish appearance. It had lost its original dark color. Yet he believed it would still have been possible to establish his ethnic affiliation by his method, the melanin dosage test.

“A similar method is now used in the United States. He stated that the scientists involved had used far more gamma rays than necessary for their experiment. He asked permission to examine a specimen of the mummy’s skin and hair, but that permission was denied. The authorities said it would damage the mummy. Later, after a certain discovery that was covered up, the scientists abandoned the mummy, suppressed all their reports, and circulated a rumor that it was not really the mummy of Ramses II.”

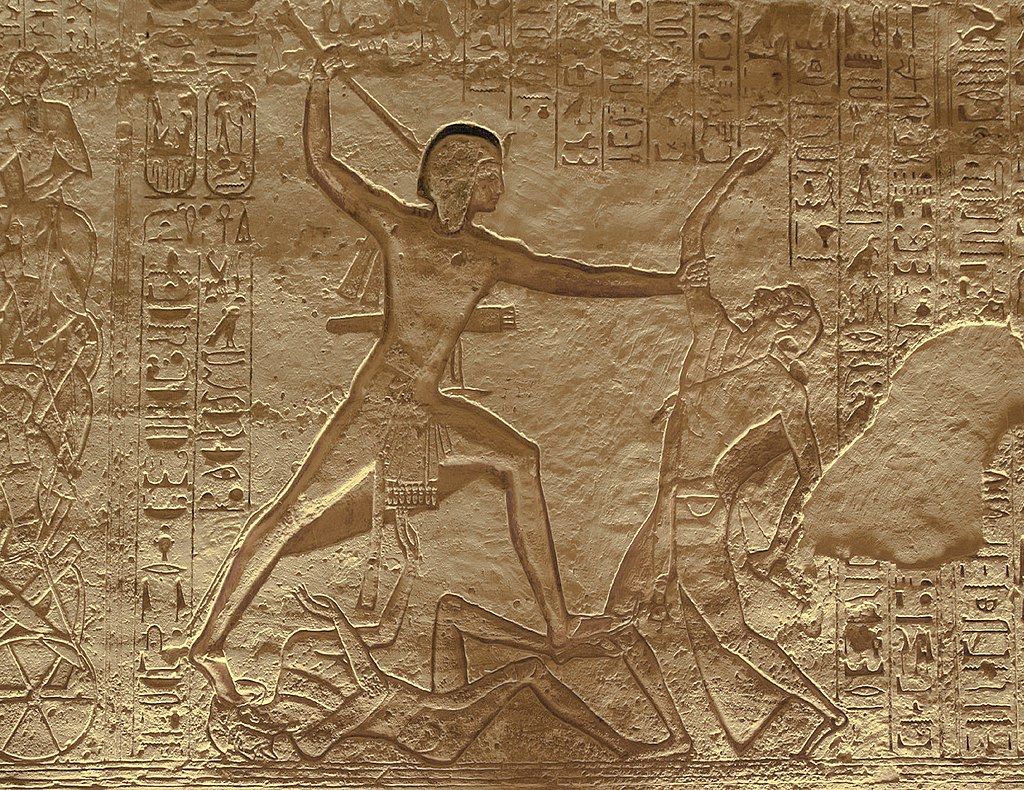

RAMSES THE MILITARIST: THE BATTLE OF KADESH

Ramses II never tired of recounting the Battle of Kadesh. The official account is inscribed on the temples of Abydos, Abu Simbel, the Ramesseum, Karnak, and Luxor, and on two hieratic papyri. It took place in the fifth year of his reign near the Orontes River in the Bekaa Valley. At that time the Kamite army was organized into four divisions, each named after one of the major deities of the kingdom: Ra, Ptah, Set, and Amun. The Egyptian contingent included the king’s pet lion and two of the monarch’s sons.

Deceived by false intelligence reports, Ramses, with only a small personal guard, found himself far ahead of the main body of his troops, and it was precisely at that moment that Kmt’s enemies attacked. Near the Syrian city of Kadesh the battle was joined, and only the personal valor and courage of Ramses saved the Kamite army from total disaster. Gathering a small group around him, Ramses charged into the Hittite lines no fewer than four times and held his small force until the Ptah division arrived to turn the tide. The monarch valued this battle enough to commemorate it on monuments throughout the Black Land. Eventually withdrawing westward, the Kamites signed a treaty with the Hittites that lasted for the remainder of Ramses’s long reign.

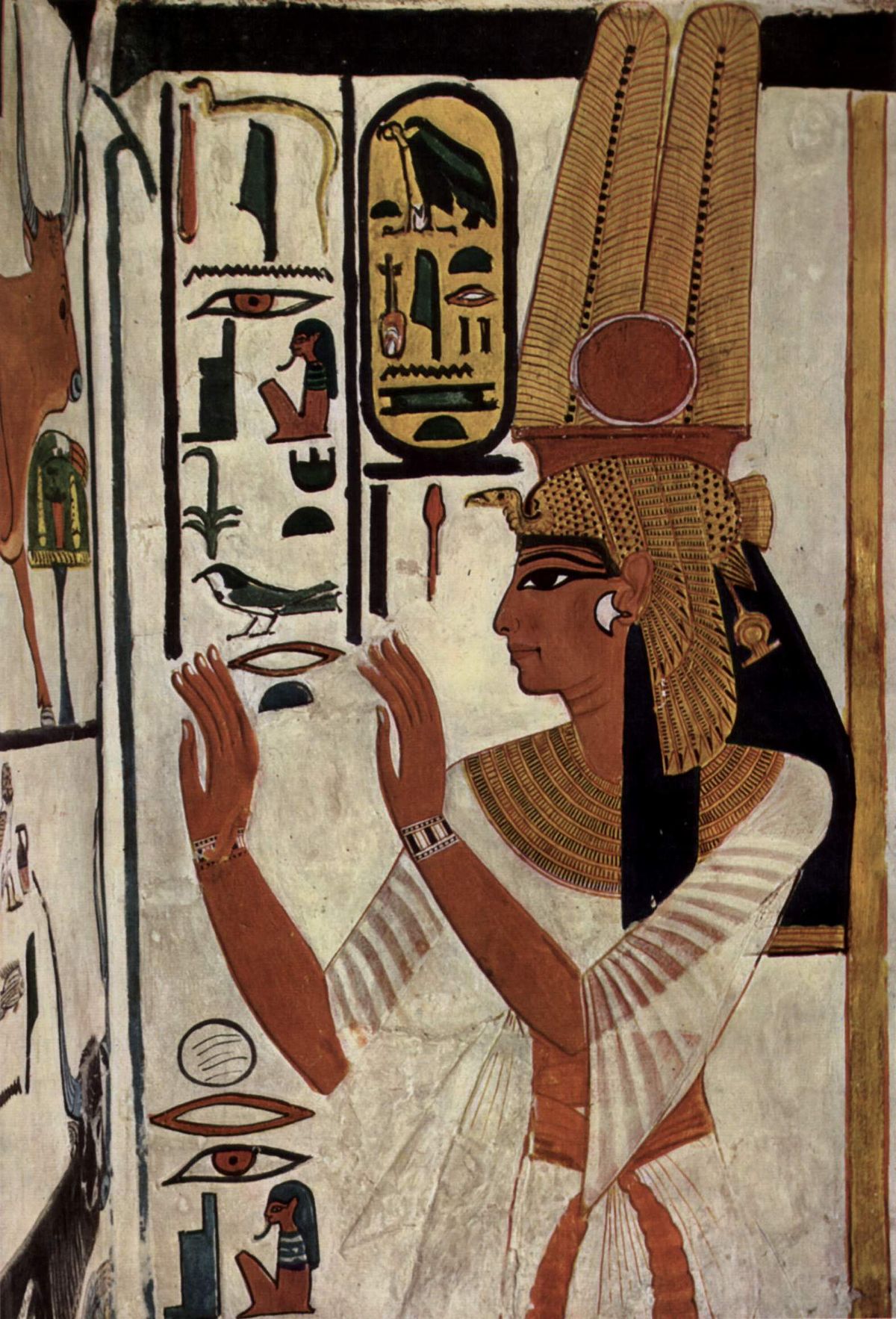

THE GREAT NEFERTARI

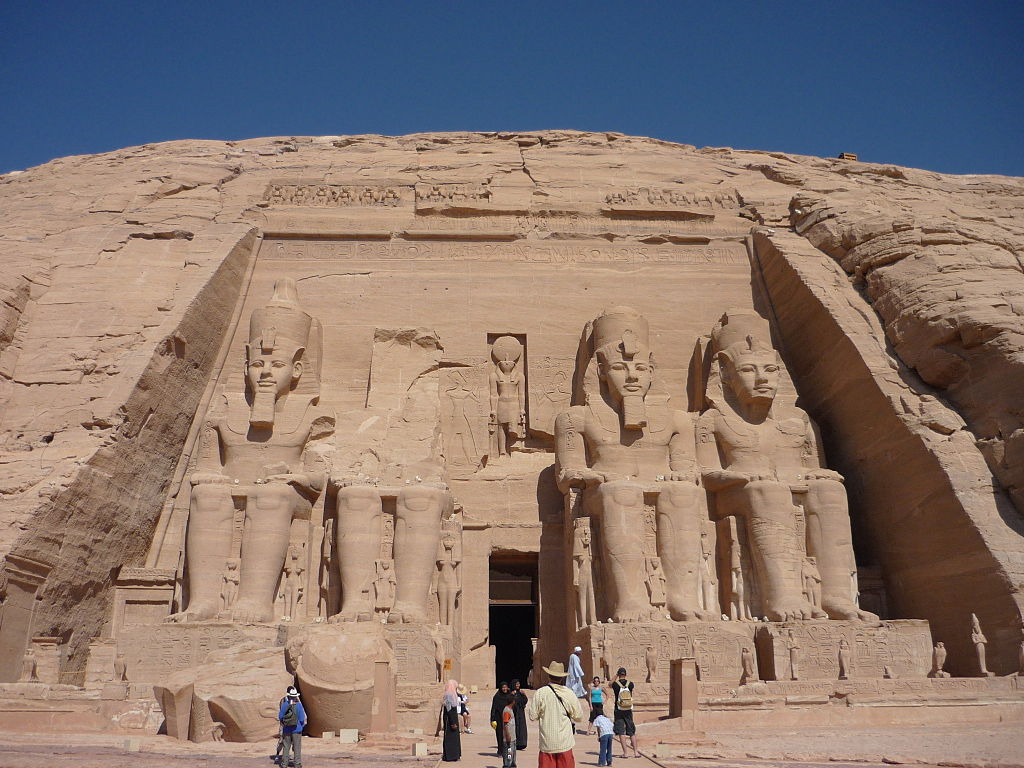

To Ramses II, Queen Nefertari was “the beautiful companion.” Her two principal titles were “Great Royal Wife” and “Mistress of the Two Lands.” The Temple of Het-Heru, the northern temple at Abu Simbel, was built by Ramses II to honor this favored wife. Between the statues of Ramses II stand those of Nefertari, and their size signifies that she was to be honored almost to the same degree as her husband in relation to the deities. The two temples of Abu Simbel were also used as storehouses for treasures and tribute demanded from Nubia, combining the essentially religious function of temples with a highly practical one.

Two building inscriptions are found there, one in the main hall and one on the façade. The first reads:

“Ramses made it as a monument for the wife of the Great King, Nefertari, beloved of Mut—a house hewn in the pure mountain of Nubia, of fine, durable white sandstone, as an eternal work.”

The second inscription says:

“Ramses-Meryamun, beloved of Amun, like Ra forever, made a house of very great monuments for the wife of the Great King Nefertari, beautiful of face…. His Majesty ordered a house to be made in Nubia hewn from the mountain. Nothing like it had ever been done before.”

After her death, Queen Nefertari was venerated as a divine Osirian, or a deified soul, and under the attributes of Asr (Osiris), Lord of the Dead, she was worshiped as a god. Nefertari was housed in a tomb of 5,200 square feet, the most splendid in the Valley of the Queens.

RAMSES THE BUILDER: ABU SIMBEL

Ramses II commissioned more buildings and erected more colossal statues than any other Kamite king. He also carved his name or reliefs on many older monuments. He launched massive building projects in Nubia, constructing temples at Beit el-Wali, Gerf Hussein, Wadi es-Sebua, Derr, Abu Simbel, and Aksha in Lower Nubia, and at Amara and Barkal in Upper Nubia. The temple of Abu Simbel, one of the greatest rock-cut structures in the world, is unquestionably a unique architectural achievement. It was carved into a mountain of sandstone on the left bank of the Nile that was considered sacred long before Ramses’s temple was cut there. It was dedicated to Re-Harakhti, the god of the rising sun, represented as a falcon-headed man wearing the solar disk. It is a masterpiece of architectural design and engineering. The temple’s orientation was entirely devoted to the worship of the rising sun, and only at certain times of the year did the vast interior become illuminated as sunlight penetrated into the sanctuary. For the ancients it must have been unforgettable to stand in the main hall at dawn and watch the life-giving sunlight gradually enter the Holy of Holies of an ancient faith.

On the façade of Abu Simbel are four colossal seated statues carved from the living rock. Two on each side of the entrance represent Ramses II wearing the double crown of Kmt. The entrance opens directly into the great hall with two rows of square pillars. On the front of these pillars are four gigantic standing statues of the king, again wearing the double crown. Each seated colossus is sixty-five feet tall, taller than the Colossi of Memnon. On the thirty-foot-high walls of the great hall are scenes and inscriptions depicting religious ceremonies and the king’s military campaigns against the Hittites.

The small temple of Abu Simbel, contemporary with the great temple, was dedicated to the ancient and illustrious goddess Het-Heru and to Queen Nefertari. Between 1964 and 1968, both temples were relocated to a new site about 210 feet farther from the river and 65 feet higher, at a cost of some $90 million.

PI-RAMSES

For Kmt’s international concerns and the reconquest of empire, a capital close to Asia and the Mediterranean was required. At Memphis of the White Walls and at Waset, Ramses had the ambition and energy to add a dazzling new urban center. The centerpiece of Pi-Ramses was the former summer palace of Seti I, which was completed and enriched by Ramses II. Pi-Ramses was also a place where Kmt’s soldiers and chariots could be housed, ready for military action.

Ramses took a strong personal interest in the city’s ornamentation and was constantly searching for new resources. He took pride in his concern for the workers. He rewarded the foreman with gold as an honor for finding a block and preparing it for use, and he assured the workers that he had filled the storehouses in advance so that “each of you will be provided for every month. I have filled the storehouse with everything—bread, meat, cakes for your food, sandals, linen, and much oil to anoint your heads every ten days and clothe you every year.”

THE KARNAK TEMPLE COMPLEX

Begun long before the time of Ramses II, the Karnak temple complex grew to become one of the largest sacred sites in the world, covering more than 250 acres. The most famous and spectacular part is the Great Hypostyle Hall. Ramses II completed this hall magnificently; it appears as a stunning forest of exactly 122 columns. The tallest rise about seventy-five feet, and many are decorated with deeply incised hieroglyphs that became a true signature of Ramses II.

THE LUXOR TEMPLE COMPLEX

The magnificent Temple of Luxor stands just over a kilometer south of the main temple at Karnak. Here Amun was worshiped in the ithyphallic form of the timeless fertility god Min. The temple is called Luxor from the Arabic el-Qusur, meaning “the castles,” the name of the village that grew on the site. The temple is largely the work of Amenhotep III and Ramses II, who added a colonnaded court and two obelisks in front of the temple. One remains; the other is in Paris, taken to France in honor of Jean-François Champollion’s decipherment of Kemetic hieroglyphs. Ramses also erected six colossal statues of himself at Luxor. Today only four survive, two seated and two standing.

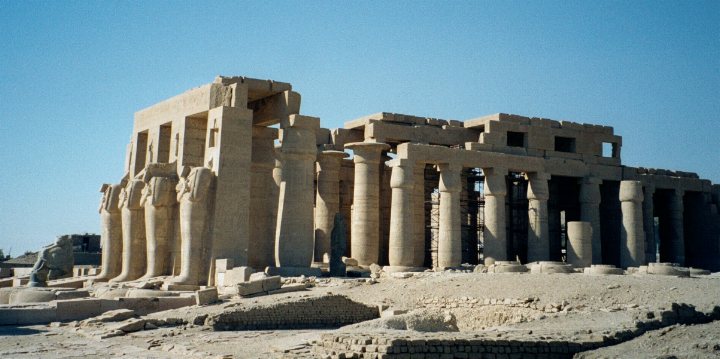

THE RAMESSEUM

THE RAMESSEUM

The Ramesseum is the mortuary temple of Ramses II on the west bank of the Nile at Luxor. It was called “The House of Millions of Years of Ramses II in the Domain of Amun.” In the first court he erected a granite statue fifty-six feet high, only slightly smaller than the Colossi of Memnon. The gigantic monolith was quarried at Aswan, ferried to Waset, unloaded, hauled several miles to the temple, and erected on site. Its original weight has been estimated at about 1,000 tons—about three times the weight of one of Hatshepsut’s obelisks at Karnak. It was in the Ramesseum that the English poet Percy Bysshe Shelley (1792–1822) found inspiration for the sonnet in which he wrote:

“My name is Ozymandias [Ramses II], king of kings; look on my works, ye Mighty, and despair!”

Today only the head, torso, and legs of the statue remain. The rest was destroyed by Christian monks determined to eradicate what they regarded as idolatry.

THE IMMORTAL RAMSES

After living vigorously for more than nine decades, Ramses II died in the second month of his sixty-seventh year of rule. In African thought, however, there was no final death, only gradual decline and periodic renewal. Egypt may have been the first nation to clearly formulate the purely African notions of resurrection and immortality. As one author succinctly put it in the Egyptian context, “if Osiris, the Nile, and all vegetation could be resurrected, so could man.” Man could be resurrected, but only if he caused the words of God—truth, justice, and righteousness—to be made manifest on earth. This was fundamental to the African (in this case, Kamite) worldview.

When we examine the civilization of Kmt, we find what may be the proudest achievement in all the annals of human history. In Kmt we see the knowledge that what African people have done, African people can do again. In this way the great deeds of our illustrious ancestors, including the incomparable Ramses II, are resurrected, and ancient history embraces both what is and what can be, laying the foundation for the forward movement of African people.

Notes and References

This brief essay is drawn from Runoko Rashidi’s book, Uncovering the African Past: The Ivan Van Sertima Papers, Books of Africa Publishing (2015).

This article is the translation of “Black History Month Special: Ramses The Great, The Pride of Africa, Set The Standard For All Rulers Who Followed,” published on February 1, 2015, on atlantablackstar.com.