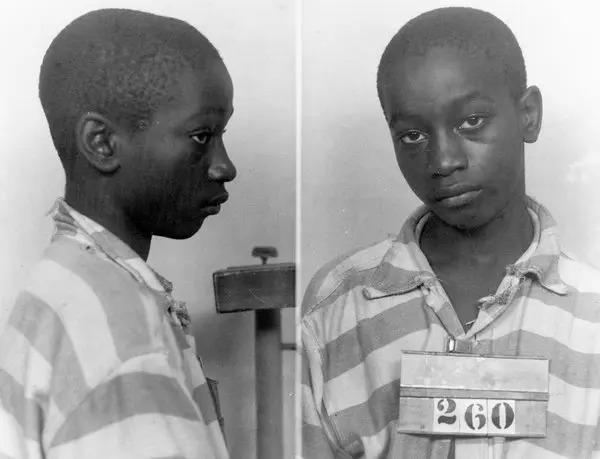

On 16 June 1944, George Stinney Jr., 14 years old, was executed in an electric chair in South Carolina. small, Black, defenseless. designated guilty, forgotten victim. a look back at one of the worst judicial crimes of the American twentieth century.

George Stinney Jr., 14 years old, executed wrongfully. and far too soon.

On 16 June 1944, in South Carolina, a fourteen-year-old Black boy was led to the electric chair. he was five feet one, weighed barely one hundred pounds. they placed a Bible on his knees so he could reach the electrodes. his name was George Junius Stinney Jr. his crime: having been seen, on a spring day, with two white girls later found dead. his trial lasted two hours. the jury (twelve white men) deliberated ten minutes. he was never granted an appeal.

It is not only the story of a judicial murder. it is the story of a system (that of segregated United States) where Black skin was enough to replace any evidence. where childhood offered no reprieve. where judicial error had no return.

Seventy years later, George Stinney would be exonerated. but what use is cleaning a name when the body was burned by the state?

Here is what a date tells. and what it continues to weigh upon American justice.

A Black child in segregated America

You don’t need a map to understand Alcolu, South Carolina. you just follow the railroad. on one side, the white houses, the post office, the school, the church with bright steeples. on the other, the Black shacks, red dust, the sawmill that offers work without fair pay. between the two, a railway line. and an invisible wall called segregation.

In 1944, Alcolu was one of those small deep Southern towns where racism was nothing exceptional. it was the rule. the order. the landscape. Black families lived with little, trapped between rural poverty and racial hierarchy. fathers cut wood, mothers cleaned houses, children grew up between segregated schools and imposed silence.

It was in this world that George Junius Stinney Jr. grew up, surrounded by his brothers and sisters. he went to the Black school, loved bikes, books, streams. he was too young to have enemies, too Black not to be a suspect.

On 23 March 1944, two white girls, Betty June Binnicker (11) and Mary Emma Thames (7), set out on bikes to pick flowers. they passed the Stinney house, asked if anyone knew where to find daisies. George and his sister Aimé answered politely.

It would be the last time they were seen alive.

The next day, their bodies were discovered, abandoned in a ditch, skulls smashed with metal. there were no fingerprints, no witness, no motive. but there was George. he was Black, he was young, and he had spoken to them.

He instantly became the main (and only) suspect.

At fourteen, George Stinney did not yet know that in that America, being seen was already being condemned. he did not know his size would not save him. he did not know they would deprive him of a lawyer, of appeal, and finally… of a future.

Justice without a trial (instant accusation)

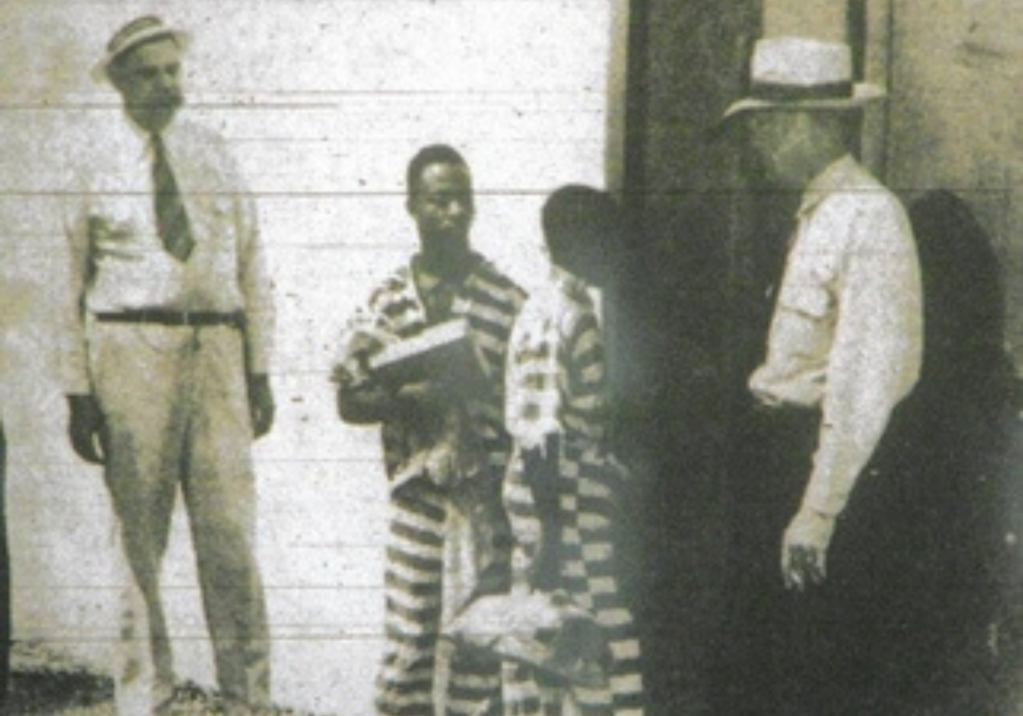

On 24 March 1944, police knocked on the Stinney door. George was arrested without explanation, without warrant, without witness. he was taken to the county jail. he would never see his family again before the execution. his sister Aimé, the last to see him free, would never be allowed to testify.

As soon as he arrived, the interrogation began. fourteen years old, alone before adult policemen. no lawyer. no parent. no witness. the interrogation was not recorded, the transcript nonexistent. the only trace: a “confession” (never released) in which George supposedly “admitted” the double murder. no one will ever know whether he spoke, or only cried. but for local justice, this was enough. the case was closed before even being built.

In 1944 South Carolina, a Black boy saying “i didn’t do it” weighed less than a white suspicion. the state was not looking for truth. it was looking for a culprit to display.

On 24 April 1944, George Stinney Jr. was led into the Clarendon County courthouse. the room was full, but no Black family was allowed inside. the jury was twelve white men. the court-appointed lawyer (a local man with no criminal defense training) called no witnesses, raised no objections, questioned nothing. George barely spoke.

The defense did not request a delay. it did not request appeal. it requested nothing.

The trial lasted less than an afternoon. the jury deliberated ten minutes. George was declared guilty. death penalty. electrocution.

The law allowed it: he had “completed” fourteen years of age, therefore old enough to die. not old enough to vote, not old enough to drink, not old enough to understand. but old enough for the state to decide he must die.

16 June 1944, the day the state killed a child

The scene unfolded in the state prison of Columbia, South Carolina. it was a little after 7 p.m. George Stinney Jr. entered the execution chamber. his hands were cuffed, his head lowered. he held a Bible. later they said he was not reading it. he kept it on his knees so he could reach the metal contact of the electric chair. he weighed only ninety-five pounds.

The chair was built for grown men. it was too wide. too high. they lifted him. they strapped him with belts around arms, legs, chest. the mask was too big for his teenage face. during electrocution, it slipped off. and everyone saw his face; contorted, burned, eyes open.

He died at 7:30 p.m. officially. unofficially, he had died long before: in the interrogation, in the trial, in the erasure. that night, the state did not kill a murderer. it killed a symbol.

The Stinney family did not stay. they were threatened. expelled. they fled the county, the town, the state. they never returned.

The grave was dug in haste. no headstone, no words. a name sometimes misspelled. a place unmarked. the pain silent. society silent as well.

Postwar America sank into patriotic euphoria. soldiers came home, suburbs were built, tragedies buried. George Stinney remained in the ground. denied, forgotten, erased.

The review: a memory awakened too late

For decades, George Stinney remained a name barely whispered, a wound without a face. the end of the twentieth century was needed for memory to revive. a local historian began digging. activists took up the case. his sister, Aimé Stinney, came forward publicly. she had forgotten nothing.

But official records were thin. some documents had disappeared. others had never been produced. yet, piece by piece, the evidence became undeniable: the trial of George Stinney violated every constitutional principle. no real defense. no fair trial. coerced confessions. a child thrown into the jaws of a racist judicial machine.

It was America that had condemned George; and another America, decades later, that began to defend him.

On 17 December 2014, judge Carmen Mullen issued her ruling: the conviction of George Stinney Jr. was vacated. seventy years after the execution, the case was reexamined. and it collapsed completely.

She spoke of a “shocking violation of justice”, of a trial “tainted with unconstitutionality”. she invoked a “cruel and unusual punishment”, a child “thrown into the jaws of a deficient judicial system”. the annulment was total. but symbolic.

None of the policemen, judges, prosecutors or officials were prosecuted. none even named posthumously. the state recognized an error without naming it a crime. justice returned, but too late to punish.

And George? he is now legally “innocent”. but still dead.

The Stinney imprint

He left neither journal nor living portrait. but George Stinney became a character; in novels, films, murals.

In 1988, novelist David Stout published Carolina Skeletons, a fictional retelling of the case. the book, adapted for television, finally gave Stinney a human face, a voice, a possibility of innocence. the following year, a TV film of the same name starring Louis Gossett Jr. brought him to the screen.

In a different register, the film the green mile (1999) by Frank Darabont, indirectly inspired by his story, portrayed a mystical, sacrificed Black death-row inmate. Stinney’s shadow lingered there, unnamed. everywhere.

Beyond fiction, George Stinney became graffiti, poem, memory ritual. on Detroit walls, in Atlanta streets, on benches at activist schools. a stolen childhood turned symbol.

The story of George Stinney goes beyond his era. it illuminates, without detour, the America of Jim Crow, where skin determined punishment and age offered no protection.

Until 2005, the United States continued executing minors. George was not an aberration. he was a precedent. and a warning.

His name is now chanted in protests against police violence. held as proof that justice can kill; and the state can lie.

George Junius Stinney Jr. was 14. he was neither guilty nor defended. only Black, poor, and alone. the rest followed.

When the law is not enough

The law said “guilty”.

History would later say “error”.

Memory, however, judges: it was a crime.

Between these three truths stands George Stinney Jr., 14, Black, alone in a white courtroom.

No witness. no defense. no return.

And behind him stand all the others. the names never carved, the graves never adorned, the silences never repaired. for the real question is not only about Stinney. it trembles in every line: how many Black children were executed with their names never spoken again?

Notes and references

“remembering the execution of 14-year-old George Stinney”, death penalty information center, 14 june 2024.

“the George Stinney tragedy”, equal justice initiative, 16 june 2025.

“George Stinney | say their names – spotlight exhibits”, stanford university exhibits.

State v. Stinney, brief of amicus curiae, civil rights & restorative justice project, northeastern university.

“coram nobis and State v. Stinney”, scholar commons, university of south carolina school of law, 2017.

Summary

George Stinney Jr., 14 years old, executed wrongly. and too soon.

A Black child in segregated America

Justice without a trial (instant accusation)

16 June 1944, the day the state killed a child

The review: a memory awakened too late

The Stinney imprint

When the law is not enough

Notes and references