Before 1848, Black people in France were theoretically free. But between racist laws, exclusions, and discrimination, equality remained an illusion.

Free, but never equal: The french paradox

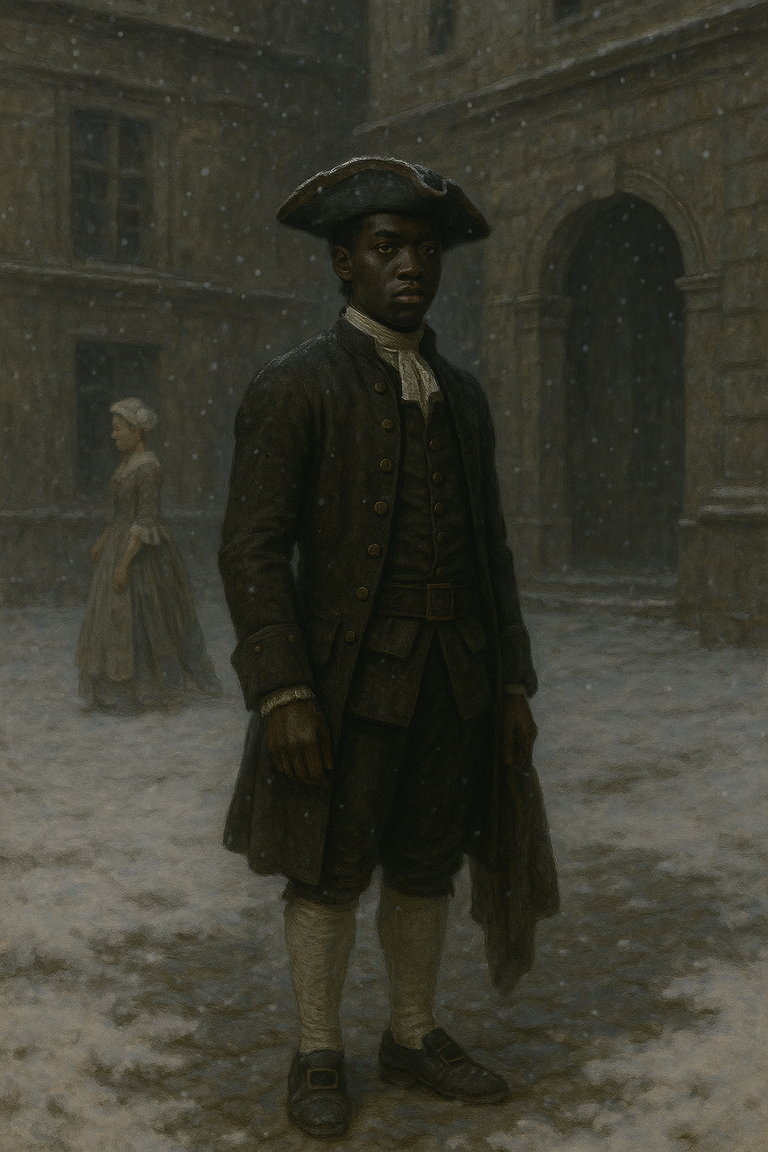

Paris, 1781.

A young man enters a high-society literary salon. He has dark skin, a proud bearing, and an aristocratic accent. Some recognize him: he is a virtuoso violinist, an excellent fencer, the acknowledged son of a Creole planter and a freed slave woman.

His name is Joseph Bologne, Chevalier de Saint-George.

Tonight, he will not perform. He will listen, smile, shine—from a distance. For although France under the Ancien Régime sometimes tolerates color, it never truly celebrates it.

He is there, but he cannot marry a white woman. He is noble, yet barred from certain offices. He is free, but his very existence provokes unease: how can a Black man be so… French?

This scene is no exception. Between 1650 and 1850, hundreds, then thousands of Africans, Caribbeans, and mixed-race individuals walked French soil. Some came from the colonies. Others were born in France. They were musicians, servants, soldiers, diplomats, shopkeepers, maids, orphans placed in noble homes. Their freedom had been proclaimed since 1315, but their rights were steadily restricted:

– Ban on entering the territory (1777)

– Ban on marrying whites (1778)

– Systematic surveillance and registration

– Invisible exclusions

Equality was just a word.

The Republic prides itself on having abolished slavery in 1848 but often forgets what came before. It forgets that for two centuries, on its own soil, it accepted the presence of Black people—provided they remained in their “place.”

This is the story of liberty without equality. Of a tolerated humanity, never fully embraced.

Today, it deserves to be told—not as a footnote, but as a fundamental part of what France once was.

A Proclaimed but conditional freedom (1315–1777)

Republican circles like to recall that France abolished slavery as early as the 14th century. In 1315, King Louis X declared:

“The soil of France frees the slave.”

This is often cited as proof of early humanism and foundational equality. But reality tells a different story.

This decree stemmed not from anti-racist conviction but from a legal strategy: to ban feudal slavery on royal land and assert the king’s authority over feudal lords. It did not apply to Africans or future colonial slaves. And it was never effectively enforced. For while the law might free, the administration often ignored it.

By the 17th century, Black men and women could be seen serving in Paris, Bordeaux, or Versailles—yet their freedom was never taken for granted.

When Louis XIV built the French colonial empire, he didn’t bother with contradictions. On one hand, France’s soil was allegedly incompatible with slavery. On the other, he enacted the Code Noir (1685), which legalized slavery in the Antilles and French Guiana. The enslaved person became a chattel, sold, transferred, punished at will.

But when Creole masters wanted to bring their enslaved people to mainland France, legal ambiguities re-emerged:

– Could one be enslaved in Paris?

– Could a “negro” be punished publicly in Bordeaux?

– Could an Antillean servant be sold in Marseille?

To clarify matters, several edicts were issued:

– 1716: Allowed enslaved individuals in France, but only for a maximum of three years.

– 1738: Mandated compulsory registration of all “Blacks and other people of color” in France.

– Marriage bans between Black people and whites introduced in certain cases.

These laws were often contested, bypassed, or nullified by local parliaments. The Paris Parliament, known for its defiance, was particularly reluctant to enforce such racist measures and freed several enslaved individuals on principle, in the name of France’s supposed honor.

Despite laws and debates, Black presence in France became a social reality.

By the late 17th century, several thousand Black and mixed-race people lived in France—mainly in Paris, Nantes, Bordeaux, and Mediterranean ports.

They were noble servants, exotic pages in salons, musicians in private orchestras, soldiers in special regiments, shopkeepers, artisans, cooks, painting models, performers in royal menageries, sometimes protected by powerful figures.

Some names stand out:

– Jean Boucaud, freed by the Paris Parliament in 1738.

– Pampy and Julienne, an enslaved man and a freedwoman, liberated in Paris in 1776.

– Zamor, enslaved by Madame du Barry, educated and freed, yet stuck in an ambiguous status.

This population lived in limbo: not formally enslaved, but never fully citizens. They were tolerated as spectacle, ornament, and domestics—but never equals.

1777: The racialization of french public space

August 9, 1777. A royal edict, unnoticed in the streets of Paris, marks a turning point in Black history in France.

The King’s Council bans the entry into France of Black people, mulattoes, and other people of color—free or enslaved.

The law doesn’t hide behind euphemisms: it’s a racial measure. It does not mention legal status but focuses on skin color.

Pigmentation becomes a criterion for exclusion.

Behind this administrative gesture lies a shift in the public space’s configuration toward racial logic. The authorities were less concerned with banning slavery—already legally unstable in France—than with limiting the visibility of Black people in cities.

The white elite feared the “contamination” of social spaces:

Too many dark faces in Marseille’s harbor, Versailles’ court, Parisian salons.

Too many Creoles, freed servants, mixed-race children. Too many liberties disrupting the colonies’ racial hierarchy.

To implement the policy, the state created an unprecedented office: the Bureau of People of Color.

Its mission:

- Register all Black, mulatto, and mixed-race individuals in France,

- Check their documents,

- Verify their “legitimacy to be there,”

- And, if needed, organize their expulsion.

It was the precursor of modern racial profiling.

Every Black man became suspicious.

Every mixed-race woman had to justify her “utility” or noble origin.

A mix of moral panic and security fantasy took root: fear of interracial marriage, “unnatural” unions, illegitimate inheritance. Births, relationships, and wealth were monitored.

This administration of skin color produced a racial reading of national space. After 1777, Blackness was seen as a threat to public order—not because of actions, but because of presence.

In 1778, the law went further: interracial marriage was officially banned.

Previously tolerated (especially among Creole aristocrats), such unions became illegal.

This was more than a moral law. It symbolically locked out Black people:

You may be educated, wealthy, cultured—but you are still outside the national community.

You may not pass on your name, your status, your legacy.

Your descendants will never be fully considered French.

This marked a rupture in French legal history.

For the first time since the Middle Ages, the state didn’t just ban a legal status—it banned a love.

A Black body could work, serve, fight, play violin… but not marry.

This was not merely a matter of morals. It was a strategy to control inheritance.

In a society where status depended on lineage, banning interracial marriage locked Black people into perpetual estrangement.

They could be tolerated if they remained occasional, decorative, marginal.

But integration, reproduction, legacy? Unacceptable.

Black figures were thus trapped:

- Those who succeeded became suspicious,

- Those who loved became criminals,

- Those who claimed rights became dangerous.

The 1777 and 1778 edicts were not anomalies.

They were the foundation of a French legal system of racialization.

And already, a testing ground for future racial policies.

A black elite under surveillance: Tolerated privileges, denied equality

He embodied everything France claimed to value: a prodigious musician, an undefeated fencer, a man of letters, a cavalry officer.

He was also a Black man, the son of a noble planter and a freed slave from Guadeloupe.

Joseph Bologne, Chevalier de Saint-George, personified the French paradox like no other—celebrated and sidelined, welcomed in salons but excluded from family lines.

He commanded a National Guard unit… yet was denied marriage, judicial office, and access to the regular army.

Despite his exceptional talent, Louis XVI refused him the direction of the Paris Opera, bowing to pressure from three white female singers who objected to being led by a “mulatto.”

It wasn’t a denial of skill. It was a rejection of what his talent represented.

Because a Black man excelling in French art threatened the myth of white superiority.

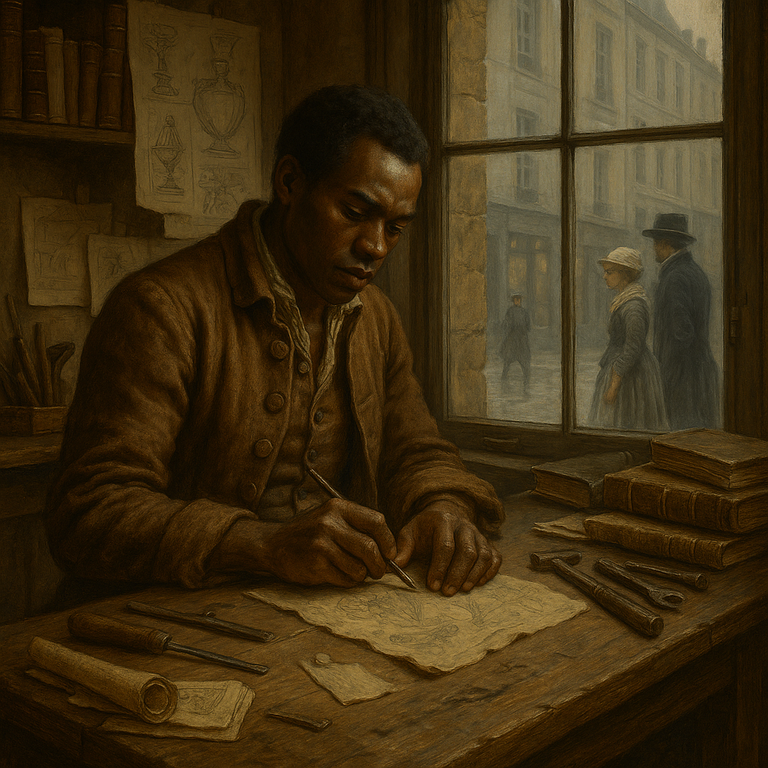

By the end of the 18th century, a small educated and wealthy Black or Creole elite emerged—sometimes noble, often property-owning, and occasionally artists. But these men (whether born free or emancipated) were never considered fully French.

- Julien Raimond, a wealthy Saint-Domingue planter, advocated in Paris for the civil rights of free people of color. He was heard but constantly pushed back into colonial space.

- Guillaume Guillon Lethière, a mixed-race painter, became a professor and later director of the French Academy in Rome—but his origin remained a stigma.

- Thomas Alexandre Dumas, general of the Republic and father of the future novelist, crossed the Alps with Bonaparte. Admired for his bravery, he was denied the honors a white man would have received without hesitation.

These men embodied a fracture: they were inside the national narrative—but never at its center.

Tolerated for their usefulness, respected for their talents, symbolic tokens—but dismissed when they demanded equality.

The place of Black women in this “phantom elite” was even more marginal and often romanticized.

They were neither citizens, heirs, nor political subjects. They were allegories.

- Ourika, a fictional character inspired by real events, was a young Senegalese woman raised in an aristocratic convent. Educated, gentle, brilliant, she fell in love with a nobleman. Society denied her that union. She ended up secluded, between madness and grief—unable to live in a world that forbade her love.

Ourika wasn’t just a romantic tragedy—she symbolized the impossibility of being Black, female, and dignified in France. - The Black Nun of Moret, rumored to be the daughter of Queen Marie-Thérèse, was raised in a royal convent. Her Black skin intrigued, frightened, and fascinated. She held no official role, no recognized rights—yet her mere presence in a royal space became a source of controversy.

These female figures, though rarely politically active, reveal one essential truth:

Even when educated, even when protected, Black women were trapped in literary roles—never recognized as legal subjects.

All these lives—Saint-George, Raimond, Lethière, Dumas, Ourika—trace the contours of a racial glass ceiling avant la lettre.

They show that France, even before formal colonization, had already built a soft system of racial exclusion.

You could be Black and brilliant—but not acknowledged.

Black and a soldier—but not honored.

Black and loved—but not married.

Black and useful—but never a full citizen.

This racism without slavery may have been even more insidious:

It allowed France to believe it was just, enlightened, egalitarian—while preserving a hierarchy of blood, skin, and legacy.

A hierarchy not written into law—but legible to all in salons, academies, and courtrooms.

The revolution and its betrayals (1791–1802)

The French Revolution exploded with the cry of human rights, liberty, and equality.

For Black people in France—Creoles, freedmen, mixed-race individuals, or descendants of slaves—it was a surge of hope.

In May 1791, after heated debates, the National Assembly passed a historic decree: free men of color born to free parents were granted the same rights as white citizens.

It was not yet the abolition of slavery, but it was a symbolic breakthrough—the racial barriers fell, at least in law.

This decision was driven by key Black figures like Julien Raimond, Vincent Ogé, and Jean-Baptiste Belley, who campaigned in Paris for civil equality.

In Saint-Domingue, Guadeloupe, and Martinique, the news alarmed white planters—they sensed the decline of their dominance.

In mainland France, it was a brief, fragile moment—but real.

For the first time, the Republic declared: color should no longer determine citizenship.

On February 4, 1794, the Convention abolished slavery in all French colonies.

The enslaved became free—and citizens.

This revolutionary decree rocked the Atlantic world.

It affirmed the Saint-Domingue slave rebellion—led by Toussaint Louverture—as the engine of change.

It also confirmed Black presence in the Republic: Jean-Baptiste Belley, a former slave turned deputy of Saint-Domingue, took his seat in the Assembly.

In France, this abolition led to greater Black visibility in public life.

They appeared in revolutionary clubs, battalions, workshops. Some received military and administrative appointments.

- Thomas Alexandre Dumas commanded an army in the Alps.

- Saint-George, previously sidelined under Louis XVI, resumed service.

For a brief moment, equality seemed achievable.

But it was an illusion.

When Napoleon Bonaparte seized power, order returned—and with it, racial hierarchies.

In May 1802, the First Consul passed a law restoring slavery in the colonies—justified economically: planters demanded their privileges back.

But the rollback didn’t stop at the colonies. In mainland France, Black people became undesirable.

Without explicit law, Napoleon orchestrated the expulsion of “too visible” Black people—especially from the colonies.

He dissolved military units with many Black soldiers.

He reinstated bans on interracial marriage, censorship, ID checks, and police surveillance.

- General Dumas was dismissed, humiliated, stripped of pay. He died poor and forgotten.

- Jean-Baptiste Belley died in prison, discredited.

- Saint-George was again rejected, despite his service.

All Black faces of the Republic disappeared from official engravings.

Between 1791 and 1802, Afro-descendants experienced:

- Hope for equality,

- Pride in national inclusion,

- Then betrayal—brutal, silent, unpunished.

Napoleon didn’t just restore slavery—he erased the Republic’s promise.

He reinstated the racial boundaries of the Ancien Régime—with greater force, bureaucracy, and cynicism.

The Black Republic that might have been was smothered at birth.

And with it, the memory of those who dreamed it.f. Et avec elle, les mémoires de ceux qui l’avaient rêvée.

Toward a fragile normalization (1804–1848)

After 1804, France entered an era of pretense.

The Napoleonic Empire, then the restored monarchy, claimed to have moved beyond revolutionary excess—while reestablishing racial order.

No law explicitly stated that Black people were unwelcome in France.

But everything—administration, society, symbolism—worked to make them invisible.

Certain professions were implicitly barred.

Authorities tracked “individuals of color” in major cities and grew alarmed when too many gathered in one place.

The racial registration system, begun in 1777, continued through prefectures and police stations.

Tolerance became conditional:

“Be discreet, useful, and most of all—alone.”

The acceptable Black person was isolated, embedded in white domesticity, with no lineage or legacy.

He could be a violinist, like Saint-George. A painter, soldier, or laborer.

But never a leader, never married to a white woman, never a property owner or bearer of political vision.

And yet, Black people did not disappear from French territory.

On the contrary, Afro-descendant presence persisted in Paris, Bordeaux, Marseille, often stemming from French colonies and former holdings.

Some were descendants of Black soldiers from the revolutionary army.

Others were former slaves freed after 1794, who returned to France.

Some were born in France to white fathers and Black mothers, trapped in legal limbo.

They lived in ports, barracks, theaters, workshops.

They were coachmen, musicians, laundresses, milliners, even cabaret owners.

But they were never seen as a community.

Everything was done to deny their collective presence.

No dedicated schools.

No memorial sites.

No political representation.

No symbolic recognition.

In 1826, an ordinance from Charles X prohibited any “foreigner or former slave” from staying more than two months in France without special authorization.

It did not mention race—but in practice, it applied almost exclusively to Black individuals.

It was covert but devastating administrative racism.

And yet, in the margins, some continued to live and love.

There were (often illegal) marriages between white women and Black men.

Mixed-race children were born, with no clear status.

Afro-descendant performers appeared in popular theaters and café-concerts.

Their presence disturbed less than before—but it did not reassure.

Equality wasn’t openly opposed—it was simply deferred, denied through inertia.

When the Second Republic abolished slavery in April 1848, following European revolutions, it did so in the colonies.

In mainland France, no effort was made to redress two centuries of discrimination suffered by free Black people.

No recognition.

No reparations for those whose dignity had been sterilized, whose rights were denied, whose histories were erased.

Nothing.

The Republic claimed to be colorblind—but it erased only white history’s accountability.

Equality was proclaimed—without naming those to whom it had long been refused.

A french history erased, but decisive

They were not shadows.They were not footnotes.They were present.Profound in their solitude.Powerful in their silence.

From Saint-George to Ourika, from Dumas to Jean Amilcar, through Zamor, Boucaud, and the Mauresse de Moret, the Afro-descendants present in France from 1650 to 1848 were neither slaves nor fully free.

They lived between the lines.

In a Republic that did not yet exist, but whose contradiction they already embodied:

How can one proclaim universality while excluding certain bodies?

Official history speaks of them as exceptions.

But the exception was the rights they were denied—not their genius, not their humanity, not their presence.

These Black men and women were the silent catalysts of an unresolved French debate:

Where does equality begin?

On the soil?

In the blood?

Through lineage?

And when history does not name you—what remains of your freedom?

We often say the Republic was born in 1789.

But we forget that its foundations were dug through silence, exclusion, and faces deliberately forgotten.

Black people in France before abolition bear witness to this denial.

Today, to rehabilitate their names, struggles, and dreams is not to repair the past:

It is to make the present more truthful.

And to open a space where Black memory is no longer a historical supplement, but a central chapter in French consciousness.

Sources

- Claude Ribbe, Le Chevalier de Saint-George, Perrin, 2004.

- Frédéric Régent, Esclavage, métissage, liberté. La Révolution française en Guadeloupe (1789–1802), Grasset, 2004.

- Pierre H. Boulle, Race et esclavage dans la France de l’Ancien Régime, PUF, 2007.

- Madeleine Dobie, Trading Places: Colonization and Slavery in Eighteenth-Century French Culture, Cornell University Press, 2010.

- Archival documents: edict of August 9, 1777 & 1778 ordinance (mixed marriages)

Table of Contents

- Free, but Never Equal: The French Paradox

- A Proclaimed but Conditional Freedom (1315–1777)

- 1777: The Racialization of French Public Space

- A Black Elite Under Surveillance: Tolerated Privileges, Denied Equality

- The Revolution and Its Betrayals (1791–1802)

- Toward a Fragile Normalization (1804–1848)

- A French History Erased, but Decisive

- Sources