What if African history didn’t begin with slavery? In this powerful article, historian Runoko Rashidi takes us back to the origins of a global diaspora that’s far too often forgotten. From the temples of Sumer to the Olmec cities, from the highlands of India to the palaces of Angkor, he uncovers an entire chapter of African heritage that predates any forced deportation.

By Runoko Rashidi – Translated and adapted for Nofi.media

Why Nofi republishes Runoko Rashidi: Before enslavement: Africa’s ancient diaspora

At Nofi, we hold a conviction: African history does not begin in the hold of slave ships. It doesn’t start in 1619, with Columbus’s arrival, nor with early abolition decrees. It is older, broader, deeper.

This is the truth that Runoko Rashidi (1954–2021), a renowned Pan-African historian, carried throughout his life—with passion, rigor, and courage. Author of several foundational works on Africa’s global presence in antiquity, he traveled across continents, drawing from archives, artifacts, oral traditions, and genetic research to reclaim the role of Black peoples in the foundations of human civilization.

We are republishing here, in French with respect and fidelity, his seminal article Before Enslavement: Africa’s Ancient Diaspora, first published in Atlanta Black Star. It’s a call to reclaim our past—a sweeping historical panorama through Asia, the Americas, and Australia—showing what classrooms too often forget: before subjugation, Africans explored, built, and inspired.

In times when identity discourse swings between erasure and folklorization, putting Rashidi’s work back into the light is a political, cultural, and educational act.

Through this republication, we wish to tell young Afro-descendant generations: you come from far away. Far beyond the chains. Far higher than what is taught about.

Welcome to the African diaspora before enslavement.

Introduction

For many years I have argued that the worst crime we can commit is to teach our children that their history begins with slavery. And yet that is precisely what many of us do in Black communities of the Western hemisphere. When Black History Month arrives, we tend to celebrate the great heroes and heroines who appeared after our deportation from Africa to the Americas. In the United States, we venerate Harriet Tubman, Frederick Douglass, Langston Hughes, Rosa Parks—for good reason. We may also mention Toussaint Louverture and Jean-Jacques Dessalines of Haiti, or even Zumbi dos Palmares in Brazil.

But many seem to forget that Africans had a history before slavery. In reality, Africa possesses an ancient diaspora with no roots in the slave trade. This brief article provides an overview of that ancient diaspora. It brings a global dimension to Black history, too rarely highlighted, and looks at what has sometimes been called “that other African.”

Not the stereotypical, primitive, savage African—but the one who first populated the Earth, who gave rise to some of the oldest and most magnificent civilizations or deeply influenced them. The one who was first to enter Asia, Europe, Australia, the Pacific, and pre-Columbian Americas—not as slaves, but as masters.

Today, we know—thanks to recent scientific studies on DNA—that modern humanity was born in Africa. Black peoples are the original people of the planet, and all modern humans can trace their ancestral roots back to Africa. Without the early migrations of those first Africans, humanity would have remained physically of African type, and the rest of the world would have been devoid of human presence.

Africa’s ancient presence in Asia

The first Asians

The first modern human populations (Homo sapiens sapiens) in Asia also originated in Africa. Here we speak of the small-statured “Africoid” peoples: phenotypically dark-skinned, tightly curled hair, often steatopygic. Today referred to—sometimes pejoratively—as “pygmies,” “Negritos,” or “negrillos,” these groups once likely reigned over vast territories. Tragically, their storied contributions to agriculture, metallurgy, writing, and urbanism have been undervalued and marginalized.

Western Asia

Sumer (biblical Shinar) was the foundational civilizing influence of ancient Western Asia, flourishing in the third millennium BCE. While its cultural and technical achievements are well-celebrated, Sumer’s ethnic origins are rarely questioned. The Sumerians called themselves “the black-headed people,” and their rulers—like Gudea—were often carved in dark stone. Their supreme deity, Anu, also evokes an African civilizing presence in early world history.

Elam, Sumer’s eastern neighbor in ancient Persia, also reveals Africoid traits—evident in the artistic remains excavated at Susa. Elam’s legendary warrior king, Memnon—celebrated in Greek epic traditions—was widely described as Black.

Phoenicia, the coastal civilizations of present-day Lebanon and northern Palestine, were part of the Canaanite hamite/kemite lineage. Biblical tradition aligns the Phoenicians, Ethiopians, and Egyptians as Black peoples hailing from the Nile Valley.

Arabia, inhabited for over 8,000 years, was also Black long before Islam. The Kaaba in Mecca held a sacred Black stone. Prophet Muhammad’s ancestry included individuals described as “black as night.” Early Muslims such as the martyr Mihdja and the famed Bilal—a man whose faith earned him the title “one-third of the faith”—were Africans. Many early converts to Islam were Black, and believers even sought refuge in Ethiopia.

South Asia

The ancient Indus (Harappan) civilization, spanning from Afghanistan’s Oxus to India’s Gulf of Cambay around 2200–1700 BCE, had Black founders—evidenced through skeletal remains, descriptions in the Rig Veda, artistic relics, Dravidian linguistic continuity, and reverence for a mother-goddess cult. As archaeologist Walter Fairservis noted, Harappans cultivated cotton and rice, domesticated chickens, perhaps invented chess, and utilized windmills.

Today, India hosts Asia’s largest Black population. The original inhabitants—Adivasis—are the ancient peoples of the land. Many Dalits, though marginalized within the caste system, share phenotypical traits and even modeled their resistance on the Black Panthers in the United States.

East and southeast Asia

Africoid ancestral traces appear in prehistoric and historical East Asia. A Japanese proverb asserts that “half the blood of a good samurai must be black.” Around the 8th century CE, Sakanouye Tamura Maro—referred to as the first shogun—was described as Black.

In China, the Shang dynasty (China’s first dynasty) was described by rivals as “black and oily of skin.” The sage Lao-Tse (6th century BCE) was said to have a dark complexion and was worshipped in magnificent temples. In Southeast Asia, the ancient Khmer founders of Funan—who established this early Kingdom of Cambodia and Vietnam—were described as small and Black, and their reverence for knowledge and impressive libraries mirrored their African heritage. They were forerunners to the monumental Khmer civilization of Angkor.

This epic African presence in Asia spans over 100,000 years—yet is little known. Despite genocide and chronic trauma, around 200 million Black peoples still live across Asia today. Their past and present achievements deserve serious attention—not just for intellectual curiosity, but to advance Pan-African solidarity and unite a separated family.

Africa’s presence in Australia & Melanesia

In Australia: A struggle for survival

Australia was populated at least 50,000 years ago by peoples who refer to themselves as “Blackfellas”—the Aboriginal Australians. Physically, they have hair ranging from straight to wavy and skin from dark to nearly black. At colonization in 1788, roughly 300,000 Aboriginal people lived across the continent in about 600 societies.

British colonization devastated them—through poisoning, massacres, introduced disease—reducing them by the 1930s to around 30,000 “full-blooded” individuals. White-written histories after 1850 largely erased their existence. By 1950, Aboriginal people were excluded from schools, hospitals, unions, the ballot box, and counted as citizens only after 1967. Today, Indigenous Australians still face alarmingly high infant mortality, poor housing, substandard education, 20-year lower life expectancy, and unemployment six times the national average.

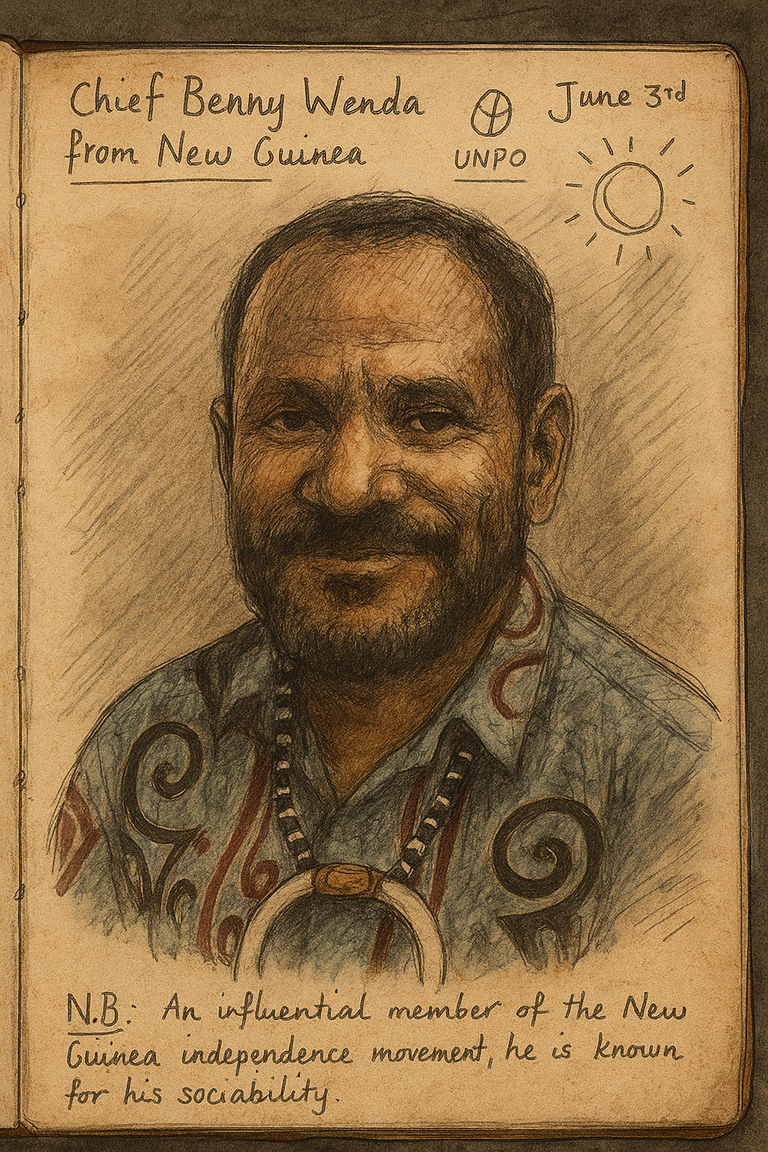

In west Papua (Melanesia): The struggle continues

New Guinea is Melanesia’s largest and most populous island. Western New Guinea, annexed by Indonesia in 1963, is home to 3–4 million Africoid people subjected to systematic violence, cultural genocide, forced labor, and demographic replacement. Their struggle needs global—and particularly Pan‑African—awareness.

Africa in pre‑columbian Americas

The ancient Olmecs of Mesoamerica—among the Western Hemisphere’s earliest civilization—flourished along Mexico’s Gulf Coast. Their colossal stone heads (weighing 10 to 40 tons) exhibit unmistakably Africoid features. Early archaeologists, such as Matthew Stirling, described them as “surprisingly negroid.” Polish craniologist Andrzej Wiercinski confirmed this in 1974, noting a “marked prevalence of the full negroid pattern” in Olmec and other pre-Christian Mexican crania.

Cultural parallels between ancient Africans and Indigenous Americans—seen in architecture and religious practices—also abound. Deities such as Ekchuah, Quetzalcoatl, Yalahau, Nahualpilli, and Ixtliltic were worshipped long before Columbus or African enslavement.

Columbus himself reported that upon landing in Haiti, locals told him Black men had preceded him from the south and southeast. In 1513, during his expedition, Balboa reported finding a colony of Black men in Darién, Panama.

All this—supported by skeletal and sculptural evidence—demonstrates that Africans played a major role in early American civilizations, long before European arrival and the slave trade.

Conclusion

Teaching a child that their history begins with slavery breaks them—perhaps forever. It feeds a new kind of mental enslavement.

Let us not confine our story to its darkest, most brutal, most traumatic chapter. Let us begin at the beginning. And that beginning did not start with enslavement. It began with Black women and men—masters of their destiny and architects of their future.

In closing, I share the profound words of Nana KwaDavid Whitaker:

“What you do for yourself depends on what you think of yourself. What you think of yourself depends on what you know of yourself. And what you know of yourself depends on what you’ve been told.”

Well said, Nana Whitaker. A powerful call and a true philosophy of history. I can imagine no better way to end this exploration of Africa’s ancient diaspora—its diaspora before enslavement.

About the author:

Runoko Rashidi (1954–August 2, 2021, Egypt) was an African‑American historian, writer, scholar, and lecturer devoted to documenting Africa’s global presence across history. Based in Los Angeles, he chronicled traces of Black history far beyond the slave trade—across Africa, Asia, Europe, Oceania, and the Americas. Author of major works including African Star over Asia: The Black Presence in the East (Books of Africa, 2012), he also led Pan‑African study tours to historic Black sites worldwide. Rashidi passed away unexpectedly in Egypt while on a research mission, leaving a visionary, militant legacy rooted in Afrocentrism, Pan‑Africanism, and the recovery of Black memories. His work continues to inspire researchers, activists, and educators around the world.

Contents

- Why Nofi republishes Runoko Rashidi: Before Enslavement: Africa’s Ancient Diaspora

- Introduction

- Africa’s presence in Asia

- The First Asians

- Western Asia

- South Asia

- East & Southeast Asia

- Africa’s presence in Australia & Melanesia

- In Australia: A struggle for survival

- West Papua in Melanesia: the continuing struggle

- Africa in Pre‑Columbian Americas

- Conclusion

- Footnotes

Footnotes

- Africoids: An anthropological term referring to human groups of African origin sharing a set of common physical traits, such as dark skin, tightly curled or coiled hair, and specific facial features. The term is now rarely used in modern anthropology due to its racialist connotations inherited from 19th-century scientific paradigms. ↩︎

- Phenotypically: Derived from the term “phenotype,” referring to all observable characteristics of an individual (skin color, skull shape, hair texture, etc.) resulting from the interaction of its genome and environment. This term is used particularly in biology, physical anthropology, and population genetics. ↩︎

- Steatopygia: A genetic trait characterized by an exaggerated accumulation of fat in the buttocks, notably observed among some populations in Southern Africa (such as the Khoisan) and Southeast Asia (like the Negritos). Historically, this physical trait has often been misrepresented through exoticized or racialized interpretations. ↩︎

- San: Indigenous people of Southern Africa, sometimes mistakenly called “Bushmen.” The San are considered one of the world’s oldest human groups, with ancient hunter-gatherer traditions and a highly developed oral culture. Their language is known for its distinct click consonants. ↩︎

- Gudea: A Sumerian ruler of the city-state of Lagash (circa 2144–2124 BCE), famous for numerous black diorite statues and devotional inscriptions. He is often cited as a model religious and political leader in ancient Mesopotamia. His depiction in dark stone has supported hypotheses about African influence in Sumer. ↩︎

- Anu: Supreme deity of the Sumerian and Akkadian pantheon, associated with the sky and divine kingship. He represents cosmic authority and is sometimes linked by Afrocentrist scholars to similarly named African deities (e.g., “Anu” in ancient Egypt). ↩︎

- Phoenicia: Ancient region corresponding to present-day Lebanon and northern Israel/Palestine, known for its thriving port cities (Tyre, Sidon, Byblos) and for inventing a consonantal alphabet—direct ancestor of the Greek and Latin alphabets. According to the Bible, the Phoenicians were related to the Canaanites, themselves brothers of the Ethiopians and Egyptians. ↩︎

- Hamite (or Kamite): Ethno-biblical category from the sons of Ham, one of Noah’s three sons according to the Book of Genesis. It designates African “Black” peoples in Judeo-Christian tradition. The term “Kamite,” popularized by Afrocentrist thinkers, is a reappropriation of Kemet (“Black land”), the ancient Egyptian name for Egypt. ↩︎

- Mihdja: Regarded in Islamic tradition as the first Muslim martyr killed in battle. Mihdja was a Black man and companion of the Prophet Muhammad. Though little is written about him in classical sources, his role symbolizes early Black presence in Islam, alongside figures like Bilal. ↩︎

- Bilal: A Black companion of the Prophet Muhammad, formerly enslaved and freed, and the first muezzin of Islam. His powerful voice and spiritual devotion made him an emblematic figure of Islam’s beginnings. Some traditions even refer to him as “one-third of the faith.” ↩︎

- Harappa: A major archaeological site of the Indus Valley Civilization, located in present-day Pakistan. Harappa gave its name to the Harappan civilization (ca. 2600–1700 BCE), one of the world’s oldest, known for urban planning, an undeciphered script, and sophisticated material culture. ↩︎

- Rig Veda: The first of four Vedas, sacred texts of Hinduism, written in Vedic Sanskrit between 1500 and 1200 BCE. Comprising over 1,000 hymns, it is among the oldest written records of Indo-European spirituality. Descriptions of Black populations in the Rig Veda have been interpreted as reflecting early conflict between Indo-Aryans and Dravidian peoples. ↩︎

- Walter Fairservis: American archaeologist and anthropologist (1921–1994), specializing in early Asian civilizations, notably the Indus Valley. He argued that the Harappans achieved a high level of social and technological organization, including early windmills, chicken domestication, and cultivation of cotton and rice. ↩︎

- Adivasis: Sanskrit for “first inhabitants,” used to designate India’s indigenous tribal peoples. They encompass a wide variety of groups often marginalized outside the caste system. Historically excluded, Adivasis represent a cultural and identity-based resistance to both Aryan and colonial dominance. ↩︎

- Dalit Panthers: A political movement founded in India in 1972 by Dalit (formerly “Untouchable”) activists, inspired by the U.S. Black Panther Party. They demanded social justice, equality, and the emancipation of oppressed caste groups, and helped frame the Dalit struggle within a broader Pan-Africanist perspective. ↩︎

- Sakanouye Tamura Maro: Japanese general from the 8th century (c. 758–811), known for his military campaigns against the Ainu, the indigenous people of northern Japan. He is often regarded as Japan’s first shogun. Some traditions describe him as a Black man, though this is not corroborated in official Japanese records. ↩︎

- Ainu: Indigenous people of Japan, primarily in Hokkaido, once also present in southern Russia. The Ainu have a unique language, culture, and phenotype distinct from majority Japanese. Subjected to forced assimilation, they were officially recognized as an indigenous minority only in 2008. ↩︎

- Blackfellas: Common term in Australia to describe Aboriginal Australians, often used by Aboriginals themselves in a reclaimed sense. It stands in contrast to “whitefellas” (white Australians). The term reflects a strong cultural identity rooted in a presence on the continent dating back over 50,000 years. ↩︎

- Andrzej Wiercinski: Polish craniologist and anthropologist active in the 1970s, known for controversial research on “Negroid” traits in pre-Columbian Mexican populations. In 1974, he presented findings to the Congress of Americanists supporting an Africoid presence among ancient Olmec sites. ↩︎

- Balboa (Vasco Núñez de): Spanish conquistador (1475–1519), famed for being the first European to reach the Pacific Ocean overland from the Americas. In 1513, in Darién (now Panama), he reportedly discovered a settlement of Black men, fueling the theory of pre-Columbian African contact. ↩︎

- Nana KwaDavid Whitaker: African-American intellectual cited by Runoko Rashidi for his philosophy of Afrocentric self-esteem. ↩︎