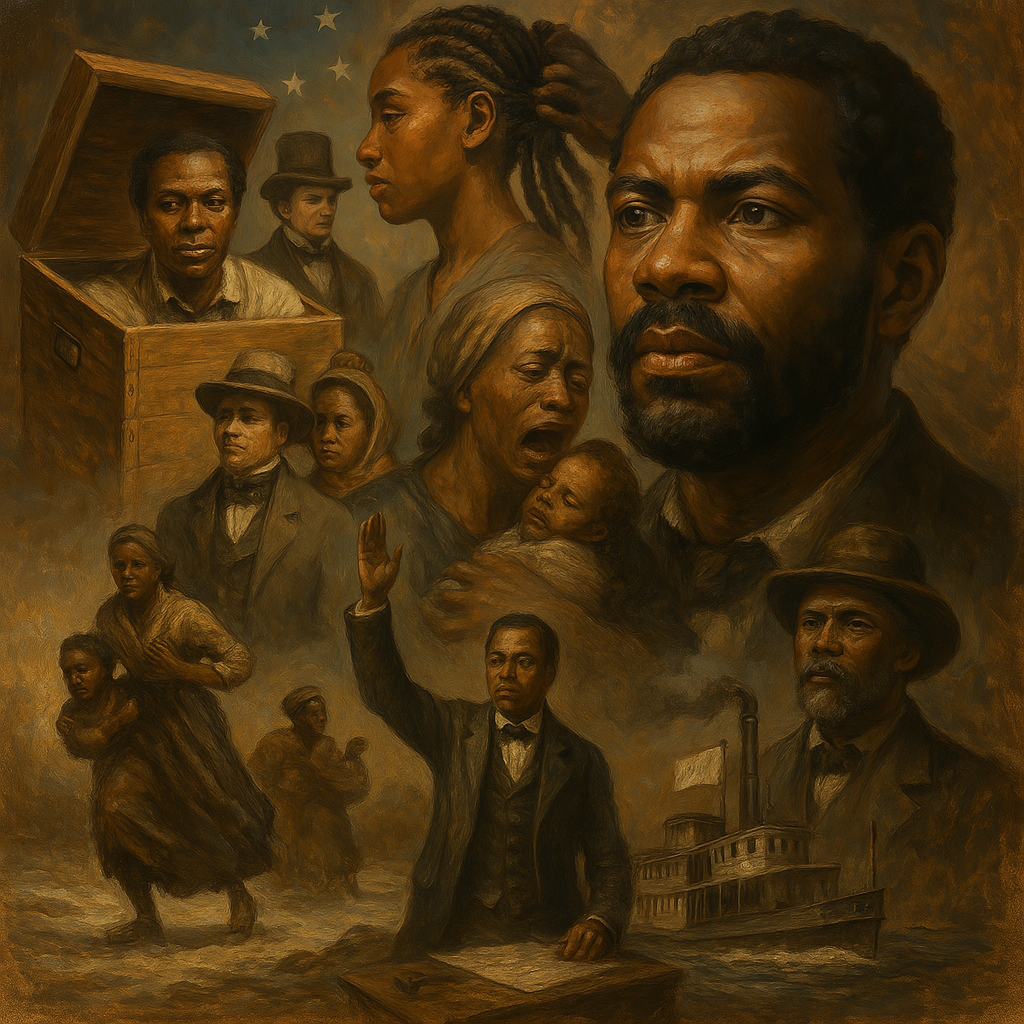

They defied the impossible. From Henry “Box” Brown’s postal escape to Eliza Harris’s icy river crossing, these enslaved people orchestrated escapes as brilliant as they were heartbreaking. Here are 8 true stories where cunning and courage shattered the chains of slavery.

The shadow of slavery and the flame of freedom

In 19th-century America, the Black slave trade and slavery were brutal realities: millions of people torn from their homelands, reduced to human property. Chains rattled, muffled screams haunted the cotton and sugarcane plantations. Whips lashed backs, families were torn apart at the auction block—a mother snatched from her child, a husband sold far from his wife. Each dawn brought a new day of forced labor under the blazing sun; each night cloaked in silence an unspeakable pain. And yet, at the heart of this hell, burned a spark that the masters could never extinguish: the stubborn hope for freedom.

Despite the terror imposed on them, enslaved people displayed extraordinary creativity and bravery in their resistance. At the risk of their lives, they devised daring escape plans, slipping through the grasp of their oppressors by incredible means. Their resistance took on countless forms: cunning, disguise, the fierce resolve of a mother willing to risk everything, or the subtle use of secret codes woven into braided hair. These true stories—one of them immortalized in literature—bear witness to the ingenuity and bravery of escaped slaves, and rekindle the memory of a relentless struggle for human dignity.

Here are eight (or even nine) astonishing stories of enslaved individuals who defied the unimaginable to reclaim their freedom.

Henry “Box” Brown: Escaping by mail

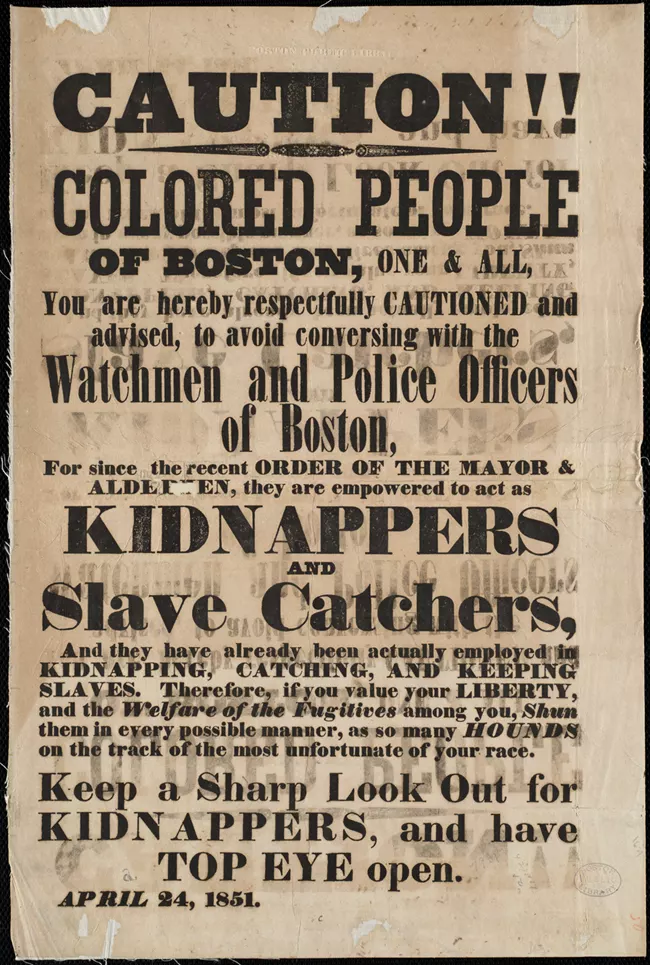

Illustration from an undated broadside published in Boston. The image references the well-known story of Henry Brown, an enslaved man who escaped from Richmond, Virginia by having himself mailed in a packing crate to Philadelphia.

One morning in March 1849, in the city of Richmond, Virginia, an enslaved Black man named Henry Brown made a wild and ingenious decision: he would mail himself to freedom. At 33 years old, Henry had just witnessed the sale of his wife and children to a slave trader—one more heartbreak that pushed him to act.

With the help of two allies—a free Black friend, James C. A. Smith, and a white shoemaker named Samuel Smith—he devised one of the boldest escape plans imaginable. Brown had a wooden crate built measuring 91 cm long, 81 cm wide, and 61 cm high—just large enough to curl his 1.73 m frame inside. The “package” had three small air holes and bore the innocent label: “dry goods.”

Henry squeezed into the box, taking with him a small bottle of water and a few biscuits. To avoid being assigned to work that day—and thereby prevent his absence from being noticed—he went so far as to burn his own hand with acid to simulate a serious injury. The box was nailed shut and secured with straps—Henry Brown was literally buried alive, staking his life on the reliability of the underground postal system. Thus began a 27-hour journey over 442 kilometers by wagon, train, steamboat, ferry, then again by train and cart.

Roughly handled by unaware transporters who tossed the box about, Henry was even flipped upside down at times despite the “Fragile” label. He endured in silence, holding his breath through every jolt, determined not to betray his presence. He later said that the thought of freedom sustained him like “an anchor of the soul, sure and steadfast” during the nightmare journey.

On March 30, 1849, the box finally arrived in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania—a free state neighboring the slaveholding South. Inside the Anti-Slavery Society’s office where the box was delivered, a few intrigued abolitionists gathered. When they loosened the straps and lifted the lid, a man emerged—numb but alive. Henry Brown rose from his “wooden tomb” like one resurrected. One witness later recalled his first words, spoken with a smile: “How do you do, gentlemen?”

Henry then sang a Biblical psalm he had chosen to celebrate his arrival on free soil. News of his miraculous postal escape spread like wildfire across the country. Henry “Box” Brown—soon nicknamed in tribute to his crate—became a living symbol of the ingenuity of enslaved people in their quest for freedom. His feat amazed the abolitionist North, where it was hailed as a “modern postal miracle,” and it terrified Southern slaveholders, who realized that no chain, not even distance, could hold back a spirit determined to break free.

Ellen and William craft: The perfect disguise

On the eve of Christmas 1848, a young enslaved couple from Macon, Georgia, executed one of the most ingenious escape plans in fugitive history. Ellen Craft, 22, was light-skinned—her mother was biracial, and her father her white enslaver. Her husband William, 24, had darker skin. Together, they imagined a daring plan: Ellen would disguise herself as a white gentleman, and William would pose as her personal servant. The idea was revolutionary—and effective—because at the time, a white woman would never travel alone with a male slave. But a sickly white master accompanied by a Black valet? That raised no eyebrows.

For weeks, they prepared the deception in utmost secrecy. Ellen cut her hair short and practiced adopting the masculine posture of the time: confident walk, upright bearing, economical gestures. She wrapped her right arm in a sling to fake an injury and avoid having to sign documents—she could neither read nor write.

To complete the disguise, she wore men’s clothing that William had purchased with his savings and partially covered her face with bandages to explain away her smooth complexion and hide her lack of facial hair. Even more cleverly, she wore green-tinted glasses, citing an eye illness, to avoid prolonged eye contact. The couple had thought of everything.

On December 21, 1848, Ellen—now unrecognizable as “Mr. William Johnson,” an ailing young planter—and William, playing “Tom,” her faithful servant, boarded a northbound train. William’s heart pounded as he adopted the submissive posture expected of an enslaved man accompanying his master. Several times, their scheme came dangerously close to collapsing. In Savannah station, a skeptical officer demanded proof that Ellen owned William.

Mute with fear, Ellen feigned outrage with grunts and gestures toward her bandaged arm, while William produced at the last second an old document proving his “ownership.” Sympathetic passengers, believing they were witnessing a sick young master harassed unjustly, stepped in to defend them, and the conductor finally allowed them to pass. At another point, a steamboat captain struck up a conversation with Ellen—worried that her soft voice might betray her, she pretended to be nearly mute due to illness and avoided further talk.

Despite these close calls, the couple traveled over 1,000 miles in just a few days, riding in first class and sleeping in the best hotels, constantly protecting their ruse. On Christmas morning 1848, Ellen and William Craft reached Philadelphia, Pennsylvania—free soil—safe and sound. Their dazzling escape, carried out as a couple in broad daylight, caused a sensation. It was quickly hailed as “the most ingenious in the history of fugitive slaves.”

Settling in Boston, the Crafts became celebrities in the abolitionist movement. They were invited to speak at public events, with Ellen’s bravery captivating audiences. She even posed in men’s clothing for a photograph widely circulated by anti-slavery activists—a visual blow to the institution of slavery.

Boston Public Library

Two years later, the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 put their freedom in jeopardy: the law allowed bounty hunters to capture fugitives even in free states. Indeed, agents were dispatched to arrest the Crafts. But Boston’s abolitionist community sprang into action, hiding the couple in a network of safe houses and making it clear that the slave catchers would not succeed. Eventually, Ellen and William, now fugitives once more, fled to England, where they finally found lasting safety.

Their escape, achieved through disguise and wit, remains one of the most daring and successful examples of resistance through deception—proof that ingenuity could outwit the shackles of slavery.

The coded hairstyles: Mapping freedom

On the plantations, slaveholders kept everything under surveillance—or so they thought. What they never imagined was that within the tight texture of simple African braids could lie the path to escape. Yet, according to the oral tradition of Afro-Colombian communities, coded hairstyles played a secret role in the quest for freedom among enslaved people. In 17th-century Colombia, Afro-descendant slaves planned escapes to the Palenques—fortified villages founded by runaway slaves in the mountains, beyond the reach of the colonists.

To guide the fugitives, women created road maps and messages by styling their hair in very specific ways. Each braid, each woven pattern became a clandestine symbol: a row of cornrows tight to the scalp might indicate winding paths through the jungle; a certain parting might mark a river or a rendezvous point. It is said that some voluminous braids, called departes, meant it was time to leave.

Picture an enslaved woman leaning over her daughter’s hair at the end of the day. Under the distracted gaze of the overseer, her fingers dance, intertwining the kinky strands. To an unknowing observer, she’s simply creating a hairstyle—perhaps a neat geometric design. But to the initiated, she is literally weaving a map: here, a road; there, some hills; further on, squares representing fields to cross.

These coded braids would then be worn proudly as a living map by the fugitive who would escape a few days later. Moreover, women sometimes concealed tiny grains—like corn or rice—inside the braids, to serve as survival rations once the escape began. It was an act of quiet rebellion, woven strand by strand, right under the noses of their oppressors.

These hairstyles formed a true capillary language of freedom. Unable to read or write and facing death if found with a drawn map, enslaved people turned a daily act—styling hair—into an ingenious way to pass on vital information. This oral tradition, handed down from generation to generation, is a testament to the creativity and solidarity that bound enslaved people together in resistance.

Each braid was a path, each hairstyle a beacon of hope: the hope of fleeing hell to reach a place where they could reclaim their humanity. (Although this chapter of history is less documented in written archives, it lives on in family stories of descendants and in the art of Afro hairstyling—a powerful reminder of the clever methods once used to secretly chart a route to freedom.)

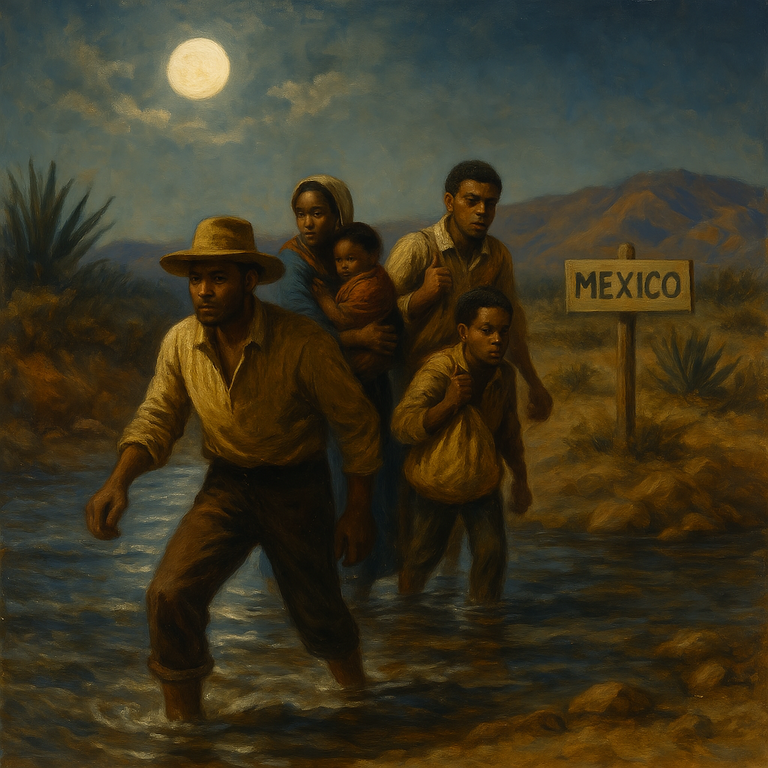

The underground railroad to Mexico

When one thinks of the “Underground Railroad,” the routes leading north—to the free states and Canada—usually come to mind. But few know that a southern route, all the way to Mexico, also offered hope to many enslaved Americans. In the mid-19th century, Mexico was a haven of freedom beyond the Rio Grande. After gaining independence, the young country formally abolished slavery in 1829 under President Vicente Guerrero, himself of Afro-Mexican descent.

This welcoming policy was maintained despite pressure from the United States: Mexican authorities refused to sign any extradition treaty for escaped slaves and declared that anyone who set foot on Mexican soil was a free person.

For many slaves from Texas, Louisiana, or Mississippi, freedom lay not to the north toward Canada but to the south, across the border. Hundreds, perhaps thousands of men and women attempted this lesser-known escape. They were called the Southern freedom seekers. Taking advantage of the border’s proximity, slaves fled Texas plantations and began long, clandestine treks toward the Rio Grande.

At night, guided by stars or sometimes aided by sympathetic Native Americans, they crossed arid plains and desert brush. Each step brought them closer to a promise: beyond the river, no master or slave hunter could legally claim them.

Texas slave owners were infuriated, knowing what it meant when whispers spread through cabins: “To the south, freedom.” Sometimes they organized raids reaching all the way to Mexico. Some bounty hunters even illegally crossed the border, pursuing escapees, only to find themselves in hostile territory where local authorities and residents often protected the newly freed.

Newspapers of the time reported cases of entire families crossing the Rio Bravo (another name for the Rio Grande) on makeshift rafts or wading across during dry seasons, fleeing in the night while slave-hunting dogs barked in the distance. On the other side, Mexican villages welcomed these exiles with kindness. Some men even enlisted in the Mexican army in exchange for land, establishing lasting Afro-Mexican communities.

This southern route to Mexico was a kind of “southern Underground Railroad.” Less organized than the one to the North, it was no less vital. Historians estimate that in the decades before the Civil War, thousands of Deep South slaves gained freedom in Mexico, to the point that this phenomenon worsened diplomatic tensions between Washington and Mexico City.

Today, the legacy of Harriet Tubman and the path to Canada is well known, but to the south, these anonymous heroes also defied injustice by walking toward the nearest land of liberty. By offering asylum to these fugitives, Mexico became a symbolic southern star on the fugitive’s compass, proving that the thirst for freedom knew no borders.

Margaret Garner: A heart-wrenching choice

One freezing night in January 1856, along the icy banks of the Ohio River, a young Black woman pushed a stolen sled toward the opposite shore. Margaret Garner, 22, had escaped a Kentucky farm with her husband Robert, their four children, and several relatives.

Bundled against the winter wind, they crossed the frozen river, their hearts pounding with the creaking ice beneath their feet. Behind them, in the dark, came the barking of dogs and the shouts of men in pursuit. The northern bank was in sight—Ohio, a free state, meant freedom if they could reach it. The scene eerily resembled that of Eliza in Uncle Tom’s Cabin, but Margaret’s story was all too real—and her race to freedom had only just begun.

The group reached Cincinnati at dawn, soaked and frozen, and hid in a relative’s house, hoping to contact the Underground Railroad to continue on to Canada. But their respite was brief. Within hours, U.S. marshals and armed slave catchers surrounded their hiding place.

Margaret and her family barricaded themselves inside, terrified. Robert Garner fired a stolen pistol in desperation, injuring a marshal. But the officers forced their way in. Margaret realized, in horror, that they would be captured. For her, returning to slavery was unthinkable. In a single dreadful moment, this young mother made a choice as horrific as it was born of love: she would rather see her children dead and free than alive and enslaved.

As the men stormed the room, Margaret grabbed a butcher knife. Holding her two-year-old daughter Mary in a final embrace, she slashed her throat. The child collapsed, dying in her mother’s arms. Margaret tried to do the same to her other terrified children—wounding them—but the marshals overpowered her in time, wresting the bloodied knife from her hands.

The scene left everyone in stunned silence. Even the hardened marshals were shaken by the sight of a mother, weeping, who had killed her own child to spare her a life of bondage. The Margaret Garner case shook a nation divided over slavery. Arrested, Margaret was jailed with her family, awaiting a sensational trial.

Her desperate act ignited fierce debate in the press: slaveholders painted her as a monstrous infanticide, while abolitionists called her a “mother of sorrow,” comparing her to Medea from mythology—thus dubbing her story the “Modern Medea.” In court, a legal battle ensued. Abolitionists wanted her tried for murder in Ohio, which would recognize her as a person and might lead to freedom or pardon.

Slaveholders, however, demanded the Fugitive Slave Act be enforced. To them, Margaret was merely “property” to be returned to her owner, and her act no more than damage to someone’s possession. After weeks of tense proceedings, slavery’s logic prevailed: Margaret and her family were declared fugitives and returned to their masters—without even a trial for the child’s death. In other words, the court ruled that by killing her enslaved baby, Margaret had merely destroyed someone else’s property—a chilling conclusion.

The rest of Margaret Garner’s story is just as tragic. Taken back by her Kentucky master, she was sold further south. In 1858, on a Mississippi plantation, she died of typhus, enslaved until the end. Her husband Robert survived until emancipation, later recounting that Margaret’s last words to him were: “Never marry again in slavery. Live in the hope of freedom.”

Her extreme act left a permanent mark on public consciousness. For many, it exemplified the ultimate cruelty of slavery—that a mother could be driven to such a choice showed that slavery was worse than death. Through her wrenching decision, Margaret Garner forced a nation to confront the inhumanity of slavery and the depths of maternal love defying it. Her story, later memorialized by Toni Morrison in the novel Beloved, remains a somber symbol of resistance in despair—a reminder of the unbearable price some were willing to pay so their children would never know chains.

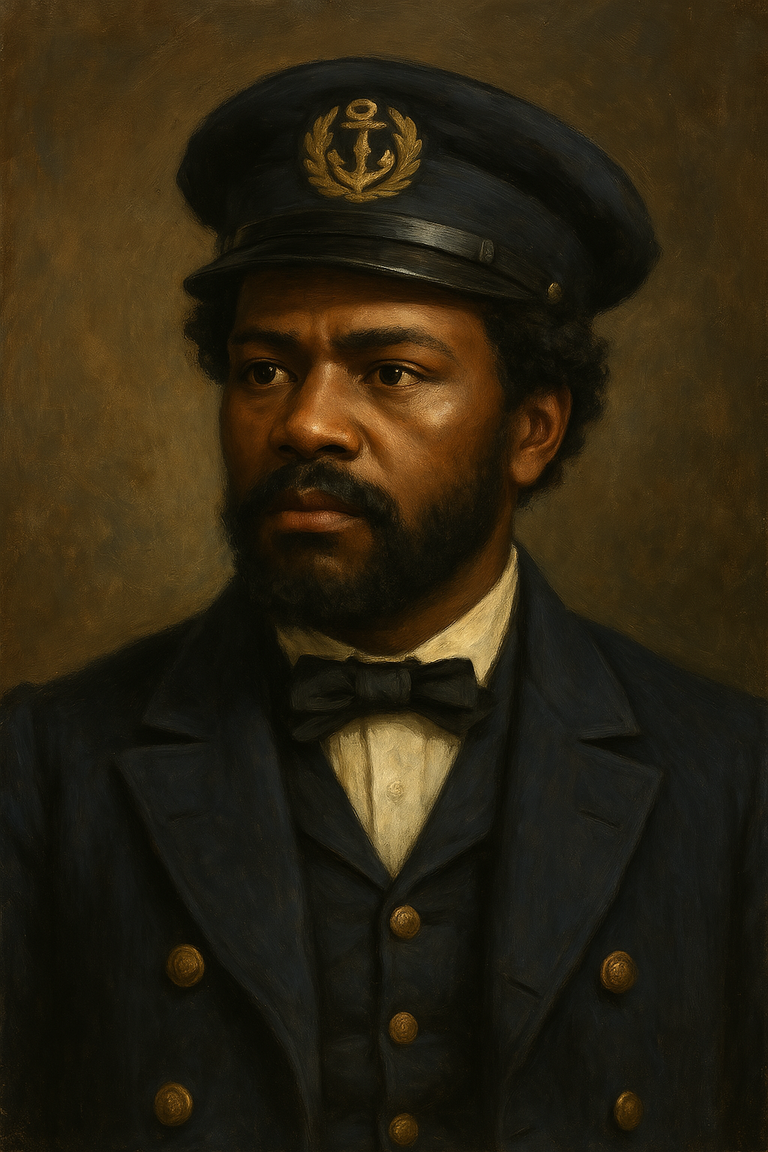

6. Robert Smalls: Captain of his own destiny

In the midst of the Civil War, in the besieged port of Charleston, a slave would carry out a feat worthy of a naval adventure novel. Robert Smalls, 23, enslaved in South Carolina, had grown up near the water and knew the sea intimately. When the war broke out, he was conscripted by the Confederacy to serve as a pilot on an armed steamer, the CSS Planter, used to transport troops and supplies.

Robert carefully observed the movements of Confederate officers aboard. Each night, the white captain left the ship to sleep on land, leaving the Planter moored and watched over only by its enslaved crew. Each morning, Smalls guided the ship through Charleston’s mined waters, saluting the Confederate forts. A bold idea took root in his mind: he would hijack the Planter and surrender it, and his crew, to the Union to win freedom.

On May 13, 1862, the opportunity arrived. Before dawn, Smalls and his fellow enslaved crew members took action. They quietly brought their families aboard—including Robert’s young wife and two children—waiting nearby in a small boat. Around 3 a.m., the Planter weighed anchor, commanded entirely by Black hands for the first time.

Wearing the captain’s long coat and straw hat (carelessly left on board), Robert took the helm. In the darkness, from a distance, he resembled the white officer. Speaking with authority, he mimicked the captain’s voice and ordered the ship toward the harbor entrance.

The steamer approached the feared Fort Sumter, still held by Confederates. It was the riskiest moment: to pass, they had to give the proper signals. Smalls, heart pounding, blew the whistle in the exact pattern and raised the correct hand signals—he had observed them for months and knew them by heart. From the fort, Confederate guards responded—and let the vessel continue.

The Planter slipped past the defenses and out into open water, where the Union blockade waited. Once the last Confederate battery was out of range, Robert raised a makeshift white flag from a broomstick. At sunrise, Union sailors were stunned by the sight: a Confederate ship approaching, white flag flying, surrendering on its own.

Robert Smalls formally handed the Planter over to Union officers, declaring:

“I bring you this war vessel, gentlemen, and with it, the freedom of her crew.”

(According to some records, a Union officer claimed Smalls had said, “I thought this boat might be of use to you,” with wry humility.)

The feat caused a national sensation. Not only had Robert freed himself, his family, and his crew, but he delivered a valuable armed vessel and firsthand intelligence on Charleston’s defenses. Union Rear Admiral Samuel Du Pont, astonished, wrote to the Secretary of the Navy:

“This man, Robert Smalls, surpasses any who have ever come into our lines… His intelligence is of the highest value.”

The rest of Robert Smalls’s life lived up to that moment. Hailed as a Union hero, he actively supported the war effort. He was appointed pilot in the U.S. Navy and later captain of the Planter itself—becoming the first Black man to command a U.S. military vessel. His bravery helped convince President Lincoln to allow Black soldiers into the Union Army.

After the war, Smalls returned to South Carolina, bought his former master’s house in Beaufort, and began a remarkable political career—elected to the state legislature and then to the U.S. Congress—advocating for the emancipation and education of formerly enslaved people.

But it is that daring night in May 1862 that remains legendary: by taking the helm of the Planter, Robert Smalls seized command of his own destiny, proving that no position of power—even captain of a warship—was beyond reach for a man determined to be free.

Eliza Harris: A frozen crossing toward freedom

One winter night, white stars shimmered over the black waters of the Ohio River. A young woman clutched a terrified child to her chest. Behind them, savage barking drew closer—tracker dogs were on their trail. Ahead, the river stretched out, scattered with drifting ice floes. Eliza had no choice. Wrapping her small son tightly in a shawl, she descended the steep bank. Her pursuers burst from the darkness, torches in hand, their flames flickering across the icy surface. Summoning every ounce of a mother’s courage, Eliza leapt onto the first floating block of ice.

The biting cold stabbed instantly at her ankles, but she felt nothing except her racing heart and the weight of her child clinging to her neck. From one ice chunk to another, she jumped, slipped, barely catching herself as the blocks cracked and the current roared below. The dogs, confused, howled at the river’s edge. Her enslavers watched in disbelief—stunned to see her leaping like an apparition across the river. With one final effort, Eliza reached the Ohio shore and collapsed on free soil, exhausted but safe.

This harrowing scene is one of the most famous moments in Harriet Beecher Stowe’s 1852 novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin. The character Eliza Harris was inspired by real accounts of slaves who actually crossed the frozen Ohio River to escape bondage in Kentucky. Stowe herself said she based Eliza on the testimony of a fugitive slave taken in by Reverend John Rankin, an Ohio abolitionist who recounted how a courageous woman had leapt across ice floes with her child in her arms, barely evading capture.

In the novel, Eliza flees upon learning that her young son, Harry, is about to be sold to a brutal trader. Terrified of losing him, she escapes in the night and reaches the flood-swollen river. The description of her crossing is gripping:

“She made a dangerous journey across the ice of the Ohio, fleeing her pursuers.”

We imagine her bleeding feet on sharp shards, her breath fogging in the frigid air, her mind obeying one command: Go, save your child!

Eliza reaches an abolitionist village in Ohio where, shivering and weeping, she is taken in by kind Quakers. Her escape doesn’t end there: in the novel, she reunites with her husband George (also a fugitive), and after many tribulations, the family reaches Canada, where slavery had been abolished in the 1830s. The power of this story deeply moved 19th-century readers—so much so that theater adaptations often featured a dramatic “Eliza crossing the river on the ice,” complete with dogs and cardboard floes onstage.

Though Eliza Harris is a fictional heroine, her courage reflects that of countless real enslaved women who braved the elements to protect their children and win their freedom. Each winter, the frozen Ohio offered a fleeting chance: a temporary road to deliverance. Local archives and oral histories confirm that many enslaved mothers attempted this desperate dash across floating ice. Many succeeded, driven by near-supernatural determination.

Not all had Eliza’s happy ending, but their memory remains a powerful testament to the unyielding will of the oppressed. Eliza, iconic figure though fictional, embodies those mothers whose love and bravery defied death and winter, so that their children might one day know the warmth of freedom.

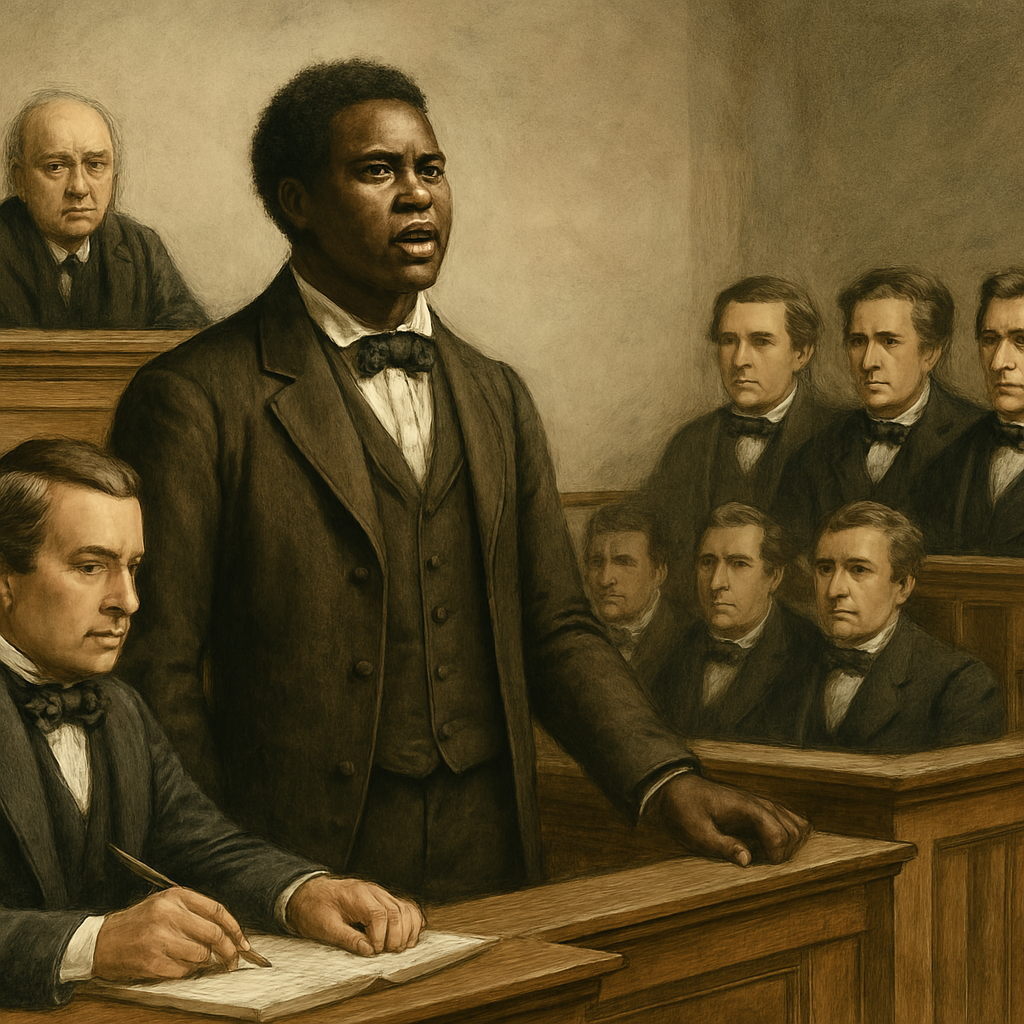

Lewis Williams: A legal escape to freedom

Not all fugitive slaves escaped by running or hiding in boxes. For some, freedom was won inside a courtroom—through a legal maneuver that challenged the very system. The story of Lewis Williams shows how a determined man exploited loopholes in the law to free himself, in what amounted to a “judicial escape.”

Lewis Williams was a slave who, in the 1840s, was taken by his owner from Missouri (a slave state) to Illinois (a free state) for a period of work. Now, in Illinois, slavery was illegal: any person voluntarily brought into the free state by their owner was considered legally free. Aware of this, Lewis decided to risk everything.

He refused to return to slave territory and filed suit in Illinois to claim his right to freedom. The case immediately raised a dilemma: was the man before the court his master’s “property” (as Southern laws insisted), or a free individual protected by the laws of the free state in which he stood?

The trial drew widespread attention. Abolitionist lawyers rallied to defend Lewis, arguing that from the moment he set foot on Illinois soil, he had become a free man. The master’s attorney countered with the Constitution and the Fugitive Slave Acts, claiming that slave status followed a person everywhere, and that the master retained every right to recover his “property.” For days, the court heard arguments.

Standing at the bar, Lewis carried the hopes of all who dreamed that the law might one day recognize the full humanity of the enslaved. In a bold verdict for the time, the judge ruled in favor of Lewis Williams: his extended presence in a free state had effectively emancipated him. Lewis was freed on the spot—he had won his liberty through the power of the law. It’s said the courtroom fell silent before erupting in barely restrained joy among abolitionist supporters, while Lewis’s master left, pale with rage.

Though lesser-known than other cases, Lewis’s story highlights an important front in the fight against slavery: the courtroom was also a battleground. Long before the Civil War, dozens of slaves sued their masters in free states or northern territories, invoking the principle that “a slave on free soil becomes free.” Some, like Dred Scott (who sadly lost his case in 1857), gained national attention, while others, like Lewis Williams, won quiet but powerful victories.

In earlier cases, the strategy had worked: for example, in 1783, a Massachusetts slave named Quock Walker used the state’s new Constitution—proclaiming that “all men are born free and equal”—to win a case against his master, effectively ending slavery in Massachusetts. In England, the 1772 Somerset case had already ruled that no person could be forcibly removed from British soil as a slave, since slavery had no legal basis there.

Lewis Williams’s escape through the legal system proves that resistance took many forms. His weapon was the law, and he wielded it to shatter his chains. Each legal victory like his shook the foundations of slavery, reminding the country that the system contradicted its own ideals of liberty and justice.

Lewis’s freedom, won in a courtroom, is proof that a slave could also be a legal strategist, turning the oppressor’s laws into keys to unlock his cage. It was, in a way, an escape without a chase—where blows were arguments and the judge who declared “Free!” shattered invisible shackles.

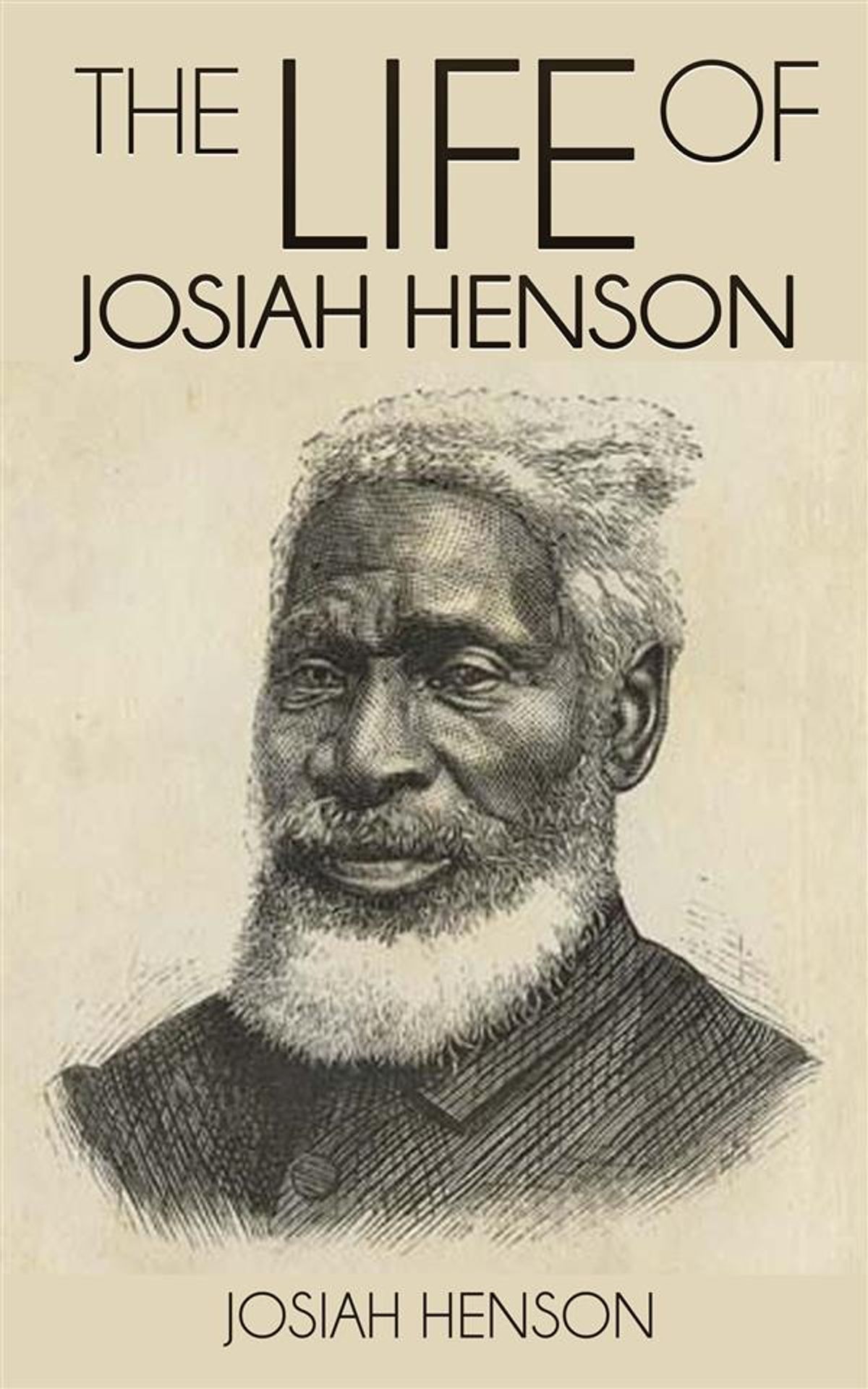

Josiah Henson: The model for uncle Tom

Born in 1789 in Maryland, Josiah Henson spent more than 40 years in slavery before achieving a daring escape to Canada—a journey that would partly inspire the legendary character “Uncle Tom” in Harriet Beecher Stowe’s novel. Henson grew up on Deep South plantations, enduring the lash and the arbitrary cruelty of masters from a young age.

Intelligent and deeply spiritual, he became a Baptist preacher on the plantation, while also serving as a respected overseer. But despite repeated promises of freedom from his various masters, Henson saw his hopes betrayed time and again—sold, resold, and kept in bondage at all costs. Nearing forty, realizing the South would never grant him liberty, he took fate into his own hands.

In 1830, Josiah Henson set out to escape with his wife and four children, the youngest only two. Their plan was bold and simple: reach Ohio, then follow the secret Underground Railroad to Upper Canada (modern-day Ontario), then under British rule, where slavery had been abolished since 1834. One night, the Hensons slipped away from the Kentucky plantation where they were held.

They traveled by night, hiding by day in woods or abandoned barns. Josiah took turns carrying his youngest children on his shoulders, pressing forward despite exhaustion. The North called to them: each time his strength flagged, Henson looked up at the North Star and found the will to continue. After weeks of grueling travel, the family reached the shores of Lake Erie.

There, helped by Quakers, they boarded a small boat and crossed the icy waters into Ontario. When Josiah finally stepped onto Canadian soil, he fell to his knees, overcome with emotion. He later wrote in his memoirs that he thanked Providence with tears, knowing that in that moment, he belonged to no one but himself.

In Canada, Henson became a pillar of the free Black community. Around 1842, he founded the Dawn Settlement near Dresden, Ontario—an agricultural colony for former slaves—with a vocational school to help freedmen gain independence. He also took up the pen to tell his story: in 1849, he published The Life of Josiah Henson, Formerly a Slave.

This powerful account caught the attention of abolitionist author Harriet Beecher Stowe as she prepared Uncle Tom’s Cabin. She partly based her character “Uncle Tom” on Henson—a patriarchal, devout, dignified slave figure.

After the novel’s enormous success, Henson published an expanded memoir in 1858 (Truth Stranger Than Fiction: Father Henson’s Story of His Own Life), as readers clamored to learn more about the “real Uncle Tom.” Unlike the fictional Tom who dies a martyr in slavery, Josiah Henson fully lived his freedom—even traveling to England, where he was received by Queen Victoria.

Until his death in 1883, Reverend Henson remained a passionate advocate for his people, proving through example what former slaves could achieve when given a chance. He had lived under Washington and Jefferson, and lived to see slavery abolished and Black rights begin to emerge. A humble yet charismatic hero, Josiah embodied resilience and goodness—the blend that made Uncle Tom a universal character.

Though the literary figure of Uncle Tom has sometimes been unjustly caricatured, the real life of Josiah Henson stands as testimony to a man who never bowed inwardly. His escape to Canada was only the beginning of a path of excellence and service. Today, in Ontario, the “Uncle Tom’s Cabin Historic Site” preserves his home and legacy—a reminder that behind fiction stood a very real man who turned his freedom into a beacon for others.

Memory of chained ingenuity

Each of these stories—whether a man sealing himself in a wooden box, a couple disguising themselves as master and slave, hidden messages braided into hair, unexpected paths to foreign soil, a mother’s heartbreaking sacrifice, a warship commandeered by a freedman, a woman’s desperate crossing on ice, a legal battle waged in a courtroom, or a future “Uncle Tom” rising to leadership—bears witness to the boundless creativity and extraordinary courage of enslaved people seeking freedom.

These men and women faced unspeakable dangers and overcame seemingly insurmountable odds, driven by one inner flame: the irresistible yearning to be free and fully human. Their stories are more than just adventures—they are acts of resistance that shook the institution of slavery and fueled the abolitionist cause.

Henry “Box” Brown showed that no wall is too thick for someone who dares to post himself to freedom;

Ellen and William Craft ridiculed racist social codes by reversing roles;

Coded braids remind us that culture and solidarity can flourish even under the harshest oppression;

The escapes to Mexico prove that the thirst for freedom doesn’t follow a compass direction;

Margaret Garner forever embodies maternal love defying dehumanization;

Robert Smalls proved that the skills of a slave could rival any free man’s when the prize was liberty;

Eliza—real or fictional—symbolizes the countless mothers whose flight north reshaped history;

Lewis Williams teaches us that law, when wielded boldly, can be a weapon against injustice;

Josiah Henson illustrates how faith, knowledge, and righteousness can raise a man from shadow to light.

By telling these stories, we honor the memory of those who suffered and resisted. We bear the duty of remembrance: in the face of the unspeakable horrors of slavery, we must never forget the heroic ingenuity it awakened in its victims. Their footsteps still echo in our conscience.

Their voices, once muffled by their masters, still whisper to future generations that freedom is worth any risk—that human dignity can triumph over chains. May these stories continue to be passed on—in books, museums, art, and conversation—so that the legacy of Black ingenuity and bravery never fades. Even in history’s darkest night, stars of resistance shone, guiding the oppressed toward the dawn of freedom.rimés vers l’aube de la liberté.

Bibliography

Books:

- Blight, David W. Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom. Simon & Schuster, 2018.

- Bordewich, Fergus M. Bound for Canaan: The Underground Railroad and the War for the Soul of America. Amistad, 2005.

- Hagedorn, Ann. Beyond the River: The Untold Story of the Heroes of the Underground Railroad. Simon & Schuster, 2004.

- Levine, Robert S. Dislocating Race and Nation: Episodes in Nineteenth-Century American Literary Nationalism. University of North Carolina Press, 2008.

- McDaniel, Karen Cotton. Ellen and William Craft: A True Story of Escape and Resistance. Ohio State University Press, 2011.

- Still, William. The Underground Railroad: A Record of Facts, Authentic Narratives, Letters, &c. Porter & Coates, 1872.

- Yellin, Jean Fagan. Harriet Jacobs: A Life. Basic Civitas Books, 2004.

Academic articles and journals:

- Gaines, Kevin K. “Robert Smalls and the Politics of Black Military Service.” Journal of Southern History, vol. 67, no. 1, 2001, pp. 95–118.

- Jones, Martha S. “Eliza Harris and the Realities of the Underground Railroad.” The William and Mary Quarterly, vol. 62, no. 3, 2010, pp. 345–372.

- Nash, Gary B. “Forging Freedom: The Formation of Philadelphia’s Black Community.” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, vol. 107, no. 1, 1983.

Primary sources:

- Brown, Henry Box. Narrative of the Life of Henry Box Brown, Written by Himself. Manchester: Lee & Glynn, 1851.

- Craft, William and Ellen. Running a Thousand Miles for Freedom; or, the Escape of William and Ellen Craft from Slavery. London: William Tweedie, 1860.

- Henson, Josiah. The Life of Josiah Henson, Formerly a Slave, Now an Inhabitant of Canada. Boston: Arthur D. Phelps, 1849.

Online sources:

- “The Underground Railroad in Mexico.” Zinn Education Project, https://www.zinnedproject.org

- “Robert Smalls.” National Park Service, https://www.nps.gov/people/robert-smalls.htm

- “Henry ‘Box’ Brown: How a Man Posted Himself to Freedom.” BBC History, https://www.bbc.co.uk/history

- “The Crafts’ Daring Escape from Slavery.” Smithsonian Magazine, https://www.smithsonianmag.com

- “Margaret Garner Case.” Ohio History Central, https://ohiohistorycentral.org/w/Margaret_Garner

Table of Contents

- The Shadow of Slavery and the Flame of Freedom

- Henry “Box” Brown: Escaping by Mail

- Ellen and William Craft: The Perfect Disguise

- The Coded Hairstyles: Mapping Freedom

- The Underground Railroad to Mexico

- Margaret Garner: A Heart-Wrenching Choice

- Robert Smalls: Captain of His Own Destiny

- Eliza Harris: A Frozen Crossing Toward Freedom

- Lewis Williams: A Legal Escape to Freedom

- Josiah Henson: The Model for Uncle Tom

- Memory of Chained Ingenuity