On April 15, 1848, seventy-seven African American slaves boarded the Pearl, a schooner meant to carry them to freedom. This escape— the largest ever attempted in the United States— was an act of astonishing courage. Though it ultimately failed, it left a lasting mark: inspiring literature, influencing law, and propelling young Black women activists to the forefront of American change. Nofi recounts the story of a crossing for freedom.

The Flight of the Invisible

Part I: Turmoil beneath the surface

On April 15, 1848, a schooner sliced through the still waters of the Potomac, its white sails barely catching the wind. Onboard, seventy-seven human beings— men, women, and children— surrendered themselves to hope. They were fleeing the invisible. Daily humiliation. Broken families. They were fleeing Washington. They were fleeing America. The name of the boat? The Pearl. A bitter maritime irony, for the gentleness evoked by its name stood in stark contrast to the grim fate that awaited it.

But this story begins long before the first wave. It takes root in the foul-smelling arteries of the District of Columbia, bureaucratic heart of a nation that, despite its Constitution, pulsed to the rhythm of the human trade. At the crossroads of Maryland and Virginia, Washington was more than a political capital: it was also a discreet but efficient hub of domestic slavery. Far from the cotton plantations of Mississippi, here the enslaved worked as cooks, seamstresses, and coachmen. They were a quiet presence at street corners, behind the carts of senators, or at the doorways of opulent salons.

Daniel Bell, a blacksmith at the Navy Yard, knew these streets better than anyone. A former enslaved man himself, his body still bore the scars of past chains. His family, however, remained in bondage. His wife Mary and their children— eight in total, plus two grandchildren— were legally the property of the widow Armistead. Her death triggered a brutal consequence: the family unit was to be sold to the highest bidder. Destination: Louisiana, Alabama, or worse still, the cane fields of New Orleans. Despite Daniel Bell’s numerous appeals to the capital’s courts, he could not save them legally. So he turned to the illegal. The unthinkable.

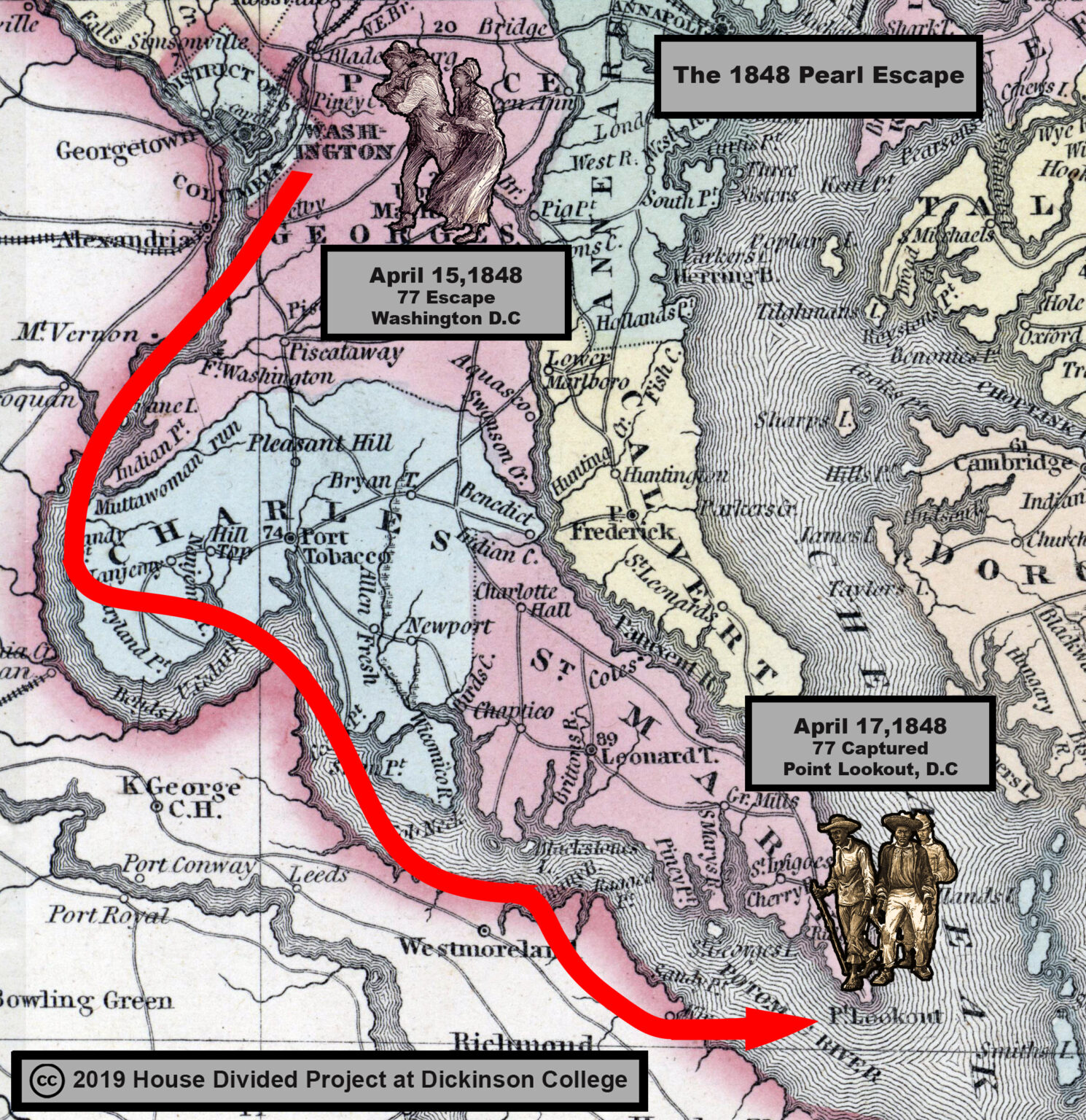

Thus was born the escape plan. First a whisper among the most trusted. Then a coded rumor, whispered in churches, passed from mouth to mouth in the back rooms of taverns frequented by free Blacks. The idea? Charter a vessel— discreet yet sturdy— and escape by water. Sail down the Potomac, avoid danger, and head up the Chesapeake Bay to Delaware, then on to New Jersey, a free state. Two hundred and twenty-five miles of silence, of water, and of promise.

To bring this wild vision to life, white allies were needed— abolitionists unafraid of prison or social ruin. William L. Chaplin, a journalist and political agitator, was among them. He contacted Gerrit Smith in New York, a prominent figure in the antislavery movement. Together, they found a captain: Daniel Drayton. A native of Philadelphia, Drayton was initially lured by profit. But he, too, held strong ideals. Alongside his partner Edward Sayres, pilot of the schooner The Pearl, he accepted the mission. A quiet man named Chester English was recruited as cook. His task was to feed the passengers during the journey. On the surface, nothing unusual. In truth, he was the silent guardian of a revolutionary plan.

As the plan took shape, more people joined the escape. No longer just the Bell family. Soon, the Edmonson sisters were added: Mary and Emily, proud-eyed teenagers. They had been “hired out” in town by their enslaver to clean homes of wealthy families. Their father, a free man, saw this operation as a final chance to liberate them from the crushing gears of slavery. The emotion of the moment can be glimpsed in the daguerreotype taken after their emancipation: a sepia-toned photograph, striking, with Mary standing tall like a reed and Emily seated, gazing at the lens as if toward the future.

On the night of departure, Washington was abuzz with echoes from Europe. The February Revolution had ousted Louis-Philippe from the French throne. People spoke of equality, republics, and human rights. In Lafayette Square, opposite the White House, senators delivered fiery speeches. The enslaved listened— from afar. But they listened. The sap of new liberty was already flowing through the spring air.

On Saturday evening, an invisible procession moved toward the docks. In the stillness of night, shadows upon the cobblestones, the fugitives boarded one by one. They did not scream. They did not cry. They hoped.

Part II: The pursuit

On the morning of April 16, 1848, Washington’s slaveholders awoke to a chilling void. Kitchens were silent. Gardens empty. The familiar footsteps on polished floors had vanished. At first, it seemed a coincidence. But the missing faces multiplied. Seventy-seven gone. An epidemic of invisibility.

Word spread quickly through the grand houses of the city center, through offices and markets. This was no ordinary escape. It was an operation. An insurrection. A slap in the face. Fear gripped white Washingtonian circles. The notion that such a large number of enslaved people could unite, organize, and attempt a collective escape… it defied the very hierarchy upon which the social order was built.

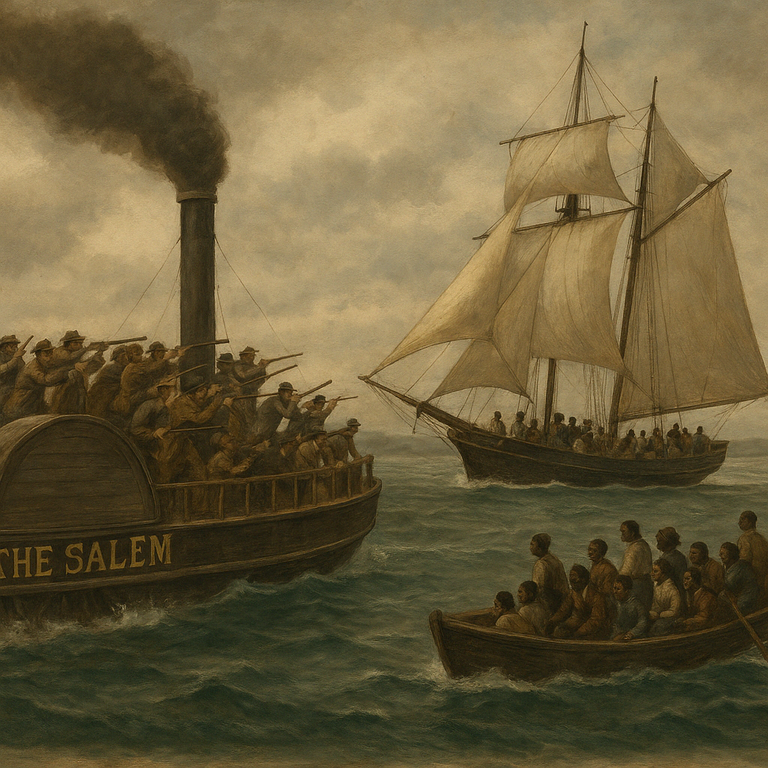

A certain Mr. Dodge, a prominent figure in Georgetown, was among the first to react. The owner of several enslaved individuals—some of whom had disappeared—he immediately made his steamboat, The Salem, available. Thirty-five men boarded, among them sons of elite families, merchants, and a few officers. Not all were driven by ideological zeal. Some were simply trying to recover their “capital.” Others hoped to avoid public scandal.

The steamboat made haste up the Potomac. Onboard, faces were tense. Armed with rifles, rumors, and a thirst for vengeance, they sped toward open water. Their target: a light schooner called The Pearl.

Meanwhile, aboard the schooner, the fugitives watched the sky. The wind was not with them. Rather than blowing northward, it stubbornly pushed against the sails. The vessel advanced slowly— sluggishly, nearly stalled on the bay’s glassy surface. Far from the port’s frenzy, it drifted at the cruel pace of the elements. Captain Drayton knew that each hour of delay raised the stakes. He had no choice but to drop anchor for the night, near Point Lookout, at the mouth of the Chesapeake.

In his memoir, published after his release, Drayton would recall that night as an overturned hourglass. Every grain of sand was a heartbeat. He knew—he could feel—that the city would not let them go without a fight. The wind was not their only enemy.

On the morning of Monday, April 17, The Salem spotted a solitary silhouette on the water. Telescopes confirmed their suspicion: it was The Pearl. The chase ended without a fight. No shots. No cries. The schooner was surrounded. The fugitives, paralyzed. Some tried to hide in the hold. Others, frozen on deck, stared at the horizon they would never reach.

The return to Washington was a scene of rare psychological violence. The fugitives were brought in two by two, in chains. They were displayed. Paraded. The spectacle of collective punishment reaffirmed white supremacy. Crowds gathered to gawk. Local newspapers described their “humble” expressions, “filthy” clothes, and “frightened” children. Language, as so often, became a second form of capture.

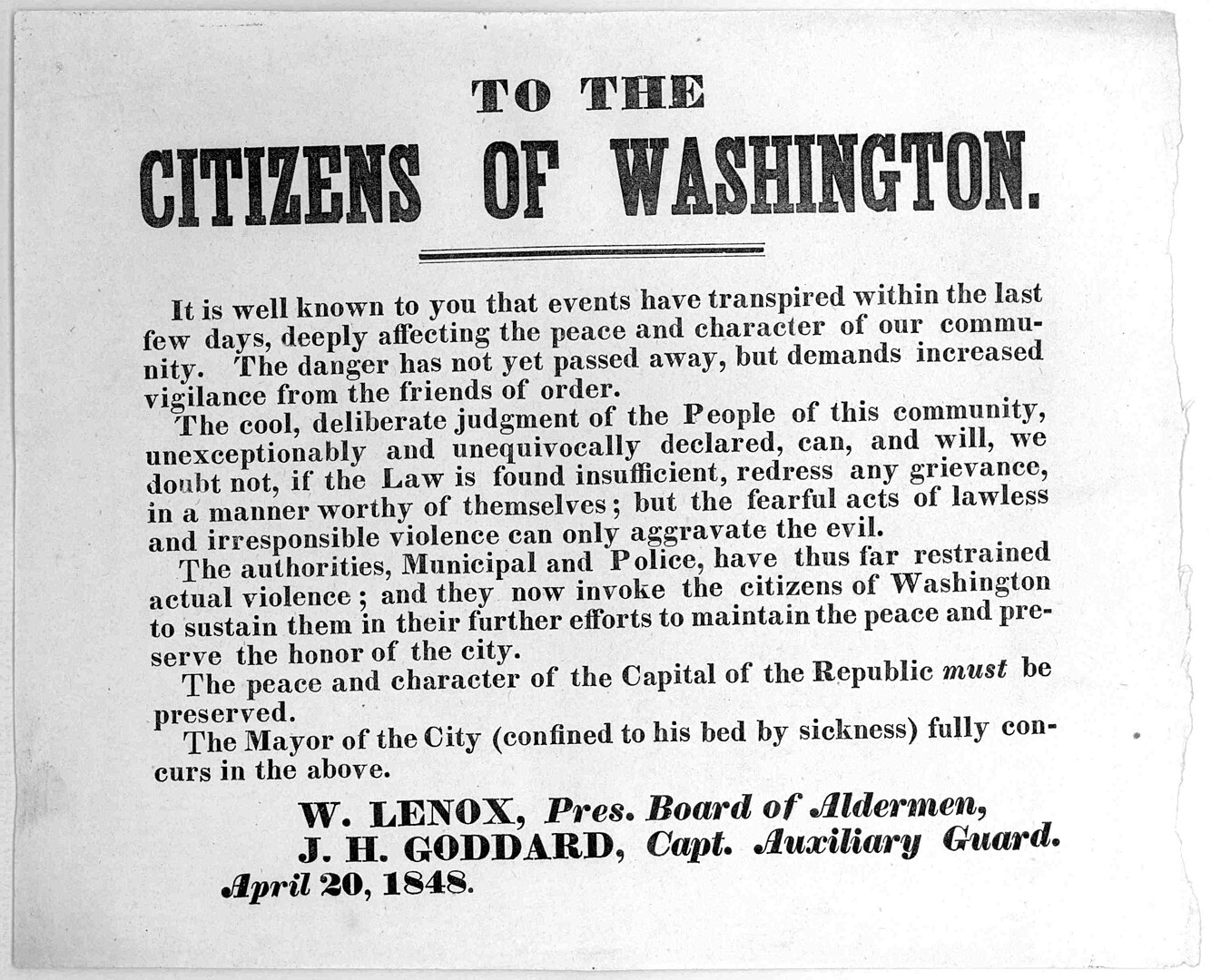

But Washington was not merely a theater of restored order. The arrival of The Pearl sent shockwaves through the city. A riot broke out, fueled by hateful speeches and fear of a Black revolt. The target? Gamaliel Bailey, editor of the abolitionist paper New Era. An armed mob stormed his office, aiming to torch the printing presses. The police—uncharacteristically swift—defended the building. But tension hung heavy. For three days, the streets were patrolled. Order was only a façade.

Meanwhile, slaveholders weighed their options. What to do with these now “problematic” fugitives? The response came swiftly: sell them in bulk to the Deep South. Louisiana. Georgia. Hell, in other words. For most, this meant the final rupture of their families and disappearance into massive plantations where life expectancy plummeted.

Yet some voices rose in protest. In Brooklyn, Reverend Henry Ward Beecher launched a fundraising campaign from his pulpit. He spoke of the Edmonson sisters—of their story, their youth, their gaze. White Northern America listened. Donations poured in. By November 1848, Mary and Emily were bought out of slavery. They left Washington as free women. They returned to school. And they chose to fight.

It was not an ending. It was an opening.

Part III: Trials, betrayal, and the weight of law

The capture of the schooner Pearl did not end the affair—rather, it thrust it into an unforgiving light. In the courtrooms and newspaper columns, it wasn’t only the escape of enslaved people being judged. It was also the sedition of the mind. White disobedience. The imagination of revolt.

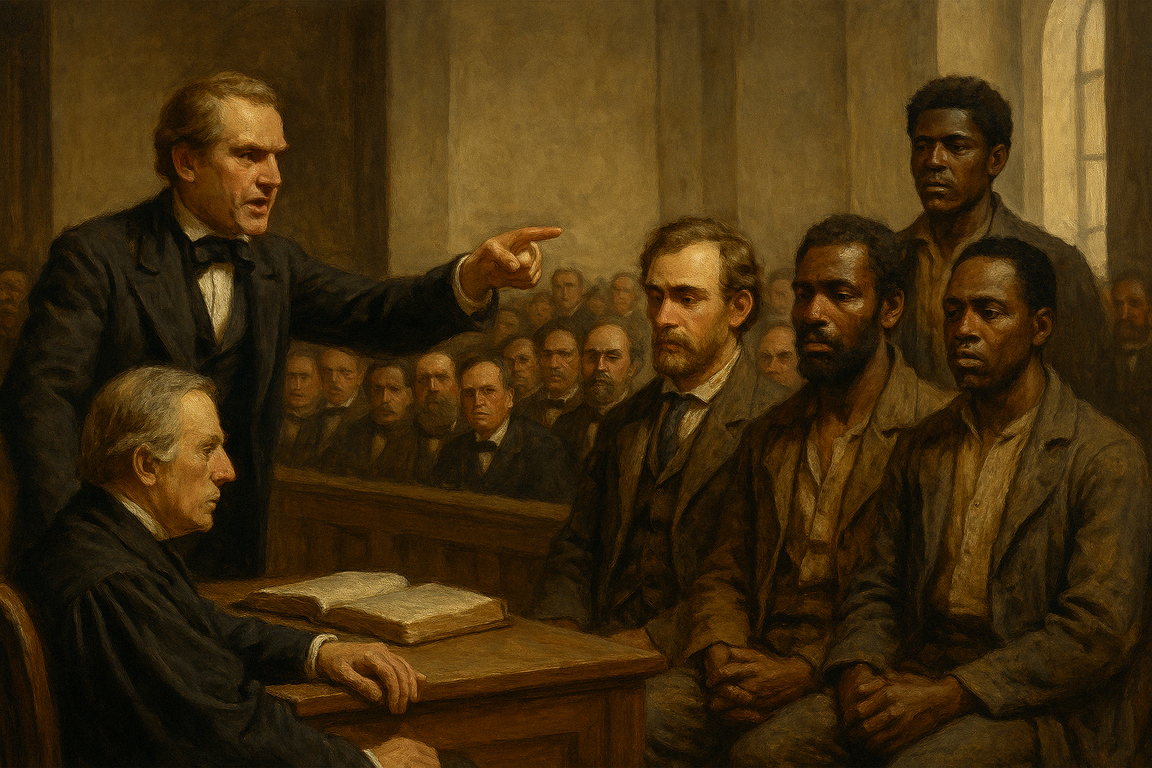

By the end of April 1848, three men were indicted: Daniel Drayton, Edward Sayres, and Chester English. The charges? Numerous. Aiding in the escape of slaves. Transporting human “property” across jurisdictional lines. Violating the tacit pact of white supremacy.

The trial of Drayton and Sayres quickly turned into a moral spectacle. Southern newspapers demanded exemplary punishment. Northern papers, more divided, sometimes responded with cautious silence. But some abolitionists—like Congressman Horace Mann—came to their defense. Mann, already known for his advocacy of public education, became the lead attorney for the two captains. He argued that Drayton had not “abducted” the slaves; he had helped them escape. A crucial distinction. But to the judges, property rights over people remained absolute.

The proceedings dragged on for months. The judicial system of the District of Columbia—already overwhelmed with other slavery cases—treated this attempt as a dangerous precedent. The district’s Attorney General, Samuel C. Busey, filed no fewer than 77 separate indictments. One for each escaped slave. Each carrying a potential fine. The strategy was clear: drown the accused in judicial debt.

Eventually, the verdicts came in: guilty. But there would be no gallows, no chains. Justice chose another punishment: slow ruin. Unable to pay the accumulated $10,000 in fines (equivalent to over $300,000 today), Drayton and Sayres were sent to Washington Jail. They would remain there for four years. Four springs without the sea. Four winters without sky.

As for Chester English, the quiet cook, he was released. Too discreet, too faceless to serve as a useful scapegoat. He slipped back into the shadows.

But that wasn’t the end. As the case unfolded in the press, a troubling question resurfaced: how could such a conspiracy have been organized without being discovered? White America wanted a mole. They found one in a name: Judson Diggs.

Diggs himself was enslaved. A hack driver in Washington, he had apparently transported one or more fugitives to the docks the night of the escape. According to testimony collected much later by John H. Paynter—a descendant of the Edmonsons—Diggs accepted money from an escapee. Then, the next day, he reported the plan to the authorities. The Black Judas of this tragedy.

Within certain Black communities, Diggs’s name became synonymous with betrayal. But his legacy remains murky. Was he complicit? Or coerced? Did he act out of fear—or greed? History, as so often, remains silent in the face of moral ambiguity.

Beyond the courtroom drama, the political impact of the Pearl Incident was immense. For antislavery activists, this mass escape attempt was irrefutable evidence: even in the nation’s capital, under the very nose of Congress, human beings still lived in bondage. The case was brought before the House of Representatives by John I. Slingerland, a New York congressman. He denounced the speed with which the fugitives had been sold and transferred, denying their families any opportunity to redeem them.

This political cry was heard. Two years later, amid extreme tensions between North and South, Congress passed the Compromise of 1850. Among its provisions was a crucial one: the abolition of the slave trade in the District of Columbia. Slavery itself remained legal there—but the image of the capital as a human marketplace had become too disturbing to ignore.

The consequences were mixed. For some, it was a step forward. For others, just another hypocrisy. The reality is that the Pearl incident had torn away a veil. It had forced America to see its capital as it truly was: a center of government, yes—but also a city of chains.

Part IV: Memory, legacy, and cultural echo

After their release, Daniel Drayton and Edward Sayres emerged from prison weakened, but unchanged in their convictions. Drayton, in particular, bore witness. In 1853, he published a memoir with a telling title: Personal Memoir of Daniel Drayton: For Four Years and Four Months a Prisoner (For Charity’s Sake) in Washington Jail. The narrative, austere yet poignant, was among the first to document from within the moral complexity of committing an illegal act in service of a just cause. He laid bare his motivations, doubts, and—above all—the profound contempt he held for the laws that sought to punish compassion.

But the most powerful legacy lay not with the rescuers, but with those they tried to free. Mary and Emily Edmonson, once liberated, became icons. They continued their education at Oberlin College—an abolitionist stronghold in Ohio—where, unusually, Black women were admitted. They joined antislavery campaigns, posed for portraits meant to awaken Northern consciousness, and spoke in churches and community halls. Their beauty, often highlighted by the press of the time, was used—sometimes against their will—to illustrate the “respectability” of runaway slaves. An ambivalent but effective image that helped sway hesitant white audiences.

Their activism grew quieter after the war, but they never disappeared completely from view. Emily lived until 1895. Mary died young, at only twenty, of tuberculosis contracted shortly after her liberation—a brutal reminder that freedom was no guarantee of survival.

Their descendants and admirers never forgot. In 1916, John H. Paynter, the Edmonson sisters’ great-grandnephew, published an essay in the Journal of Negro History founded by Carter G. Woodson. Titled The Fugitives of the Pearl, the text crystallized the memory of the incident within African American historical tradition. Blending fact and family stories, it clearly named both traitors and heroes. It was also one of the first to recall the involvement of Paul Jennings, a former slave of James Madison, in the escape’s organization.

Jennings, a discreet man, had already published his own memoir. In A Colored Man’s Reminiscences of James Madison (1865), he painted an intimate portrait of the White House during slavery, while subtly alluding to his abolitionist activities. Long overlooked, his role in the Pearl story was later rediscovered through archival research in the 20th century. Today, scholars consider him a key figure in Washington’s underground history.

The Pearl, as a historical object, entered popular culture as well. Harriet Beecher Stowe, moved by the story of the escape and the Edmonson sisters, drew inspiration from it for her novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Published in 1852, it became an immediate bestseller. Though the characters were not direct representations, the themes of being “sold South” and the despair in the face of legal injustice were clear echoes. Stowe, who had attended a fundraiser for the Edmonsons in Brooklyn, thus paid them a veiled—yet invaluable—tribute.

And yet, for over a century, the Pearl incident was absent from school textbooks. Neither standardized history books nor major museums gave it the place it deserved. Only at the end of the 20th century did the story reemerge, thanks to African American historiography, heritage activism, and the rediscovery of D.C.’s court records.

In the 2000s, several academic works filled the silence. Escape on the Pearl by Mary Kay Ricks, published in 2007, offered a vivid and well-documented account based on court archives, oral testimonies, and family records. Historian Josephine Pacheco of the University of Maryland proposed a more legal and political analysis in The Pearl: A Failed Slave Escape on the Potomac—just as essential.

This rediscovery did not stay confined to academia. In 2017, as part of Washington’s waterfront redevelopment, a street was named Pearl Street. The gesture was not just symbolic—it was political. In a capital still haunted by the ghosts of its past, this street became a daily reminder that freedom had also traveled by water.

In visual arts, the memory of The Pearl resurfaced too. Photography exhibits, documentaries, and community murals emerged. Artist Sonya Clark incorporated references to the Pearl into her weavings on slavery and freedom. Theater pieces were staged in Baltimore, D.C., and Philadelphia—places where the ship had passed or was meant to arrive. Everywhere, the schooner became a symbol. Not of failure—but of daring.

Today, the story of The Pearl is taught in some historically Black universities as a paradigm of collective resistance. It features in educational programs of the National Museum of African American History and Culture. And it continues to resurface in activist speeches about reparations, in Juneteenth commemorations, and in debates over urban memory.

The Pearl may never have reached New Jersey. But its wake still stirs the waters of American history.

Part V: What the pearl still tells us about America

There are stories we discover late. Not because they were lost, but because they were deliberately silenced. The Pearl incident is one of those troubling narratives long pushed to the margins of America’s gilded national story. Not because it was insignificant—quite the opposite—but because it revealed the unacceptable.

What did The Pearl say in 1848, and what does it still say today?

First, it said that enslaved people were not passive. That the official history lied. That beyond the narratives of submission, there existed organized, strategic, and communal forms of resistance. That enslaved people didn’t run away because they “lacked adaptation,” as 19th-century publications sometimes claimed, but because they were sentient beings—conscious, thinking, driven by their own will. The Pearl was the collective manifestation of that will.

It also showed that the North and the South—so often depicted as irreconcilable opposites in history textbooks—were far more porous. White men from the North helped orchestrate the escape; Black traitors from the South betrayed it. Nothing was simple. Nothing ever is. And it is in that complexity, that contradictory humanity, that the strength of this story lies.

More than anything, it revealed how the law served injustice. That men could be condemned for helping other human beings reach freedom—this simple fact is enough to overturn the fable of neutral law. The Pearl incident was, too, a battle against the very institutions of the Republic when those institutions became tools of enslavement.

And then, The Pearl spoke of memory. For more than a century, it was ignored, erased. And yet, its waves never stopped returning. In the civil rights movement, in the speeches of Martin Luther King, in the cries of the children of Ferguson, Baltimore, Minneapolis… The Pearl comes back, in new forms. It speaks of migration, of shattered dreams, of broken promises. It speaks of borders, of water, of flight.

In the America of 2025, marked by new social fractures, The Pearl takes on a singular resonance. At a time when African American history is again under attack, censored, or denied in some states, the escape of The Pearl becomes more than a historical fact. It becomes an act of remembrance.

A memory that some still try to bury—under laws, silences, or statues—but that, like the fugitives of that April night, always returns by water.

It returns in the name of a street in D.C., in a forgotten book rediscovered in a library, in a play performed in a neighborhood school, in an urban mural tracing the silhouette of a schooner on a concrete wall.

Above all, it returns as a reminder:

That freedom is not given. It must be claimed. By oar, by sail, by voice.

And that sometimes, even when it fails, it leaves behind a wake so powerful that it changes the course of rivers.

Notes and References

- Mary Kay Ricks, Escape on the Pearl: The Heroic Bid for Freedom on the Underground Railroad, New York, William Morrow, 2007. — A detailed and accessible account of the planning, capture, and legacy of the escape.

- Josephine F. Pacheco, The Pearl: A Failed Slave Escape on the Potomac, Chapel Hill, University of North Carolina Press, 2005. — A legal and political analysis based on the District of Columbia’s archives.

- Daniel Drayton, Personal Memoir of Daniel Drayton: For Four Years and Four Months a Prisoner (For Charity’s Sake) in Washington Jail, Boston, B. Marsh, 1853. — A firsthand account by the Pearl’s captain, written shortly after his release.

- John H. Paynter, “The Fugitives of the Pearl,” The Journal of Negro History, vol. 1, no. 3, July 1916, pp. 1–22. — A historical and familial narrative by a descendant of the Edmonson family.

- Paul Jennings, A Colored Man’s Reminiscences of James Madison, Boston, 1865. — The memoirs of a former White House slave, revealing his involvement in the Pearl incident.

- Harriet Beecher Stowe, Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Boston, John P. Jewett & Co., 1852; reprinted Garden City, Doubleday, 1960. — A novel partially inspired by the fate of the Edmonson sisters.

- Chris Myers Asch & George Derek Musgrove, Chocolate City: A History of Race and Democracy in the Nation’s Capital, Chapel Hill, UNC Press, 2017. — A social and political history of Washington, D.C., including the Pearl’s role.

- David L. Lewis, District of Columbia: A Bicentennial History, New York, W. W. Norton, 1976. — An analysis of the legislative context of the Compromise of 1850 and its local consequences.

- U.S. National Archives (NARA), “Appraisal of the Estate of Robert Armistead, 1832,” Record Group RG21. — An original document listing the Bell family among the enslaved.

- National Museum of African American History and Culture, The Pearl Incident Educational Resource Pack, Washington, D.C., 2019. — A recent and concise educational toolkit on the incident.

Summary

The Flight of the Invisible

- Part I: Turmoil Beneath the Surface

- Part II: The Pursuit

- Part III: Trials, Betrayal, and the Weight of Law

- Part IV: Memory, Legacy, and Cultural Echo

- Part V: What The Pearl Still Tells Us About America

- Notes and References