From London to Port of Spain, Michael X crossed the 1960s preaching Black emancipation while flirting with controversy. Activist, cultural icon, fugitive, and finally a man sentenced to death, his meteoric path continues to provoke questions. What remains of the radical revolutionary once supported by John Lennon?

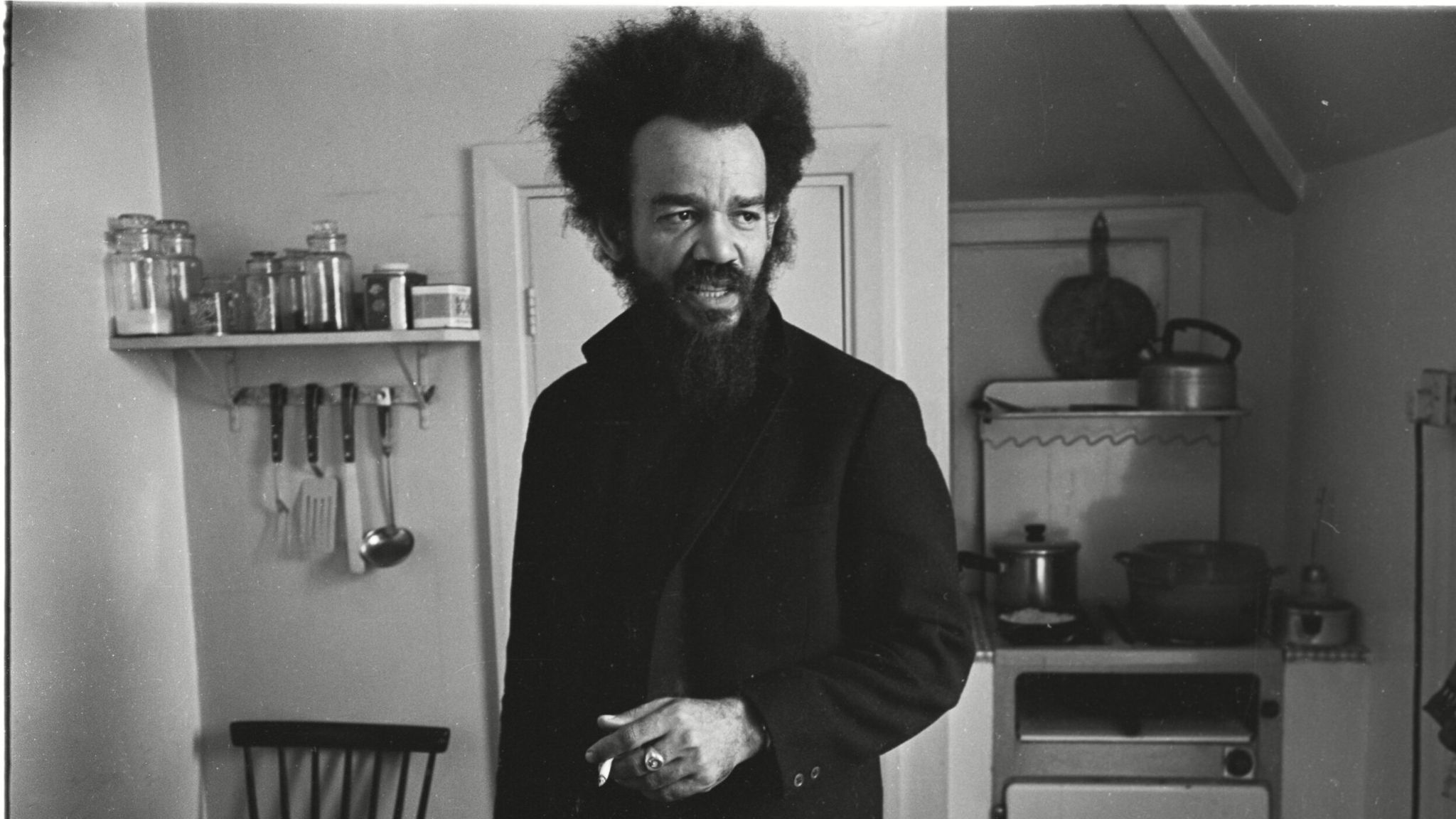

He carried several names, as one carries several lives. Michael X. Michael Abdul Malik. Truthfully, even he seemed unsure which one defined him best.

He was born in Trinidad, on the warm soil of an empire no longer spoken of, yet still governed by colonial laws that shaped bodies and minds. He would end up hanged in a Port of Spain prison, accused of murder. In between, he had been a street poet, an activist, a figure in British Black Power, an alleged conman, a self-declared mystic, a ghetto godfather, and a friend of John Lennon.

His journey was anything but linear—full of voids, tensions, and contradictions.

In London during the 1960s, he was both the voice of Black anger and the target of a justice system still steeped in institutional racism.

In Trinidad, he tried to replay the revolution under the palm trees, until the bodies began to pile up and his support crumbled.

Michael X is one of those figures History prefers not to recount. Too provocative to be sanctified. Too complex to be erased. He never settled for protest: he wanted to subvert, to shock, to deconstruct England from within.

And in that effort, he went from symbol to pariah.

In post-colonial London, he briefly embodied Black pride in a white world.

But what remains of this man today? A silhouette in a film. A code name in an archive. A slave collar turned manifesto.

Michael X didn’t merely pass through his time—he shook it, until it broke him.

I. A man of his time: Between exile and the search for identity

A. Caribbean roots and turbulent youth

Trinidad, 1933. The island was still a British colony, and children were not born free—they were born categorized.

Michael de Freitas entered a world marked by racial, social, and linguistic hierarchies.

His father was Barbadian, his mother Portuguese. An unusual mix in the streets of Belmont, and more importantly, an ambiguous blend that placed him on the margins of communal divides. Too Black to be white, too white to be Black.

He grew up with this dissonance tattooed onto his skin.

He understood early on that he would have to invent his own place. He watched the colonizers, the judges, the police—all white. He grasped that the language of authority was Oxford English. So he mimicked it. Mastered it. Turned it against them.

As a teenager, he left. Destination: London.

He left the Caribbean with dreams of grandeur, only to discover—like so many migrants from the Commonwealth—the brutal reality of a racialized metropolis.

London did not welcome him as a subject of the Empire, but as an intruder.

In the 1950s, he survived as a nightclub doorman, bouncer, and chauffeur. But he made a name for himself in the shadowy world of housing rackets. Alongside Peter Rachman, the notorious slum landlord of Notting Hill, he became an enforcer—sharp and intimidating.

Already, his gaze was striking: brilliant, cutting, elusive.

He was not yet Michael X. But he was preparing.

B. The encounter with Malcolm X and the birth of an activist

It was Malcolm X who set him ablaze.

When the African American leader arrived in London in February 1965, Michael was still Michael de Freitas, a shady figure of the West End. But in Malcolm’s words, he heard something no British speech had ever offered him:

Uncompromising Black dignity.

It wasn’t just a meeting. It was a revelation.

A few days later, Malcolm X was assassinated in New York. Michael made it his life vow.

He changed his name. He became Michael Abdul Malik, then Michael X. The X was a tribute—but also an enigma, a provocation. He erased his colonial name, rejected the logic of enslaved lineage. And he embraced the fiery language of American Black Power, adapted to British realities.

But England wasn’t Harlem. It had neither Martin Luther King nor Rosa Parks nor the Nation of Islam. It had the Queen, Scotland Yard, and the BBC.

From now on, Michael X would be a problem.

II. The rise of black activism in the United Kingdom

A. Britain’s racial landscape in the 1960s

London, 1960s. Often imagined as free, modern, vibrant. But for Afro-Caribbeans arriving from the colonies, the British capital was a maze of rejection.

No “Whites Only” signs—but invisible borders in streets, pubs, and schools. No segregation laws—but daily discrimination, normalized and politely accepted.

Jobs, housing, education, policing—every institution a wall.

By the late 1950s, the Notting Hill riots (1958) erupted like thunder: white youths, spurred on by fascist rhetoric, attacked Black immigrants. For several nights, the streets shook with screams and beatings. The state’s response? Minimal. Silent.

It was in this vacuum, between rage and abandonment, that Michael X found his voice.

England gave him no space? He created one.

He didn’t just want to denounce racism—he wanted to make it a radical political fight, a liberation discourse rooted in the British experience.

B. The racial adjustment action society and the black house

In 1965, he founded the Racial Adjustment Action Society (RAAS)—a biting acronym for a serious cause. It was one of the first radical Black movements in Britain, well before the British Black Panther Party. Its aim? To re-educate Black youth, defend their rights, and deracialize society through confrontation.

But Michael X didn’t just build a movement—he built a place. In Notting Hill, he founded the Black House, a communal, political, spiritual, and artistic space. You’d find militants, boxers, artists, poets. They talked rebellion, held conferences, and lived together—Black, for Black.

The project was compelling. But it also unsettled.

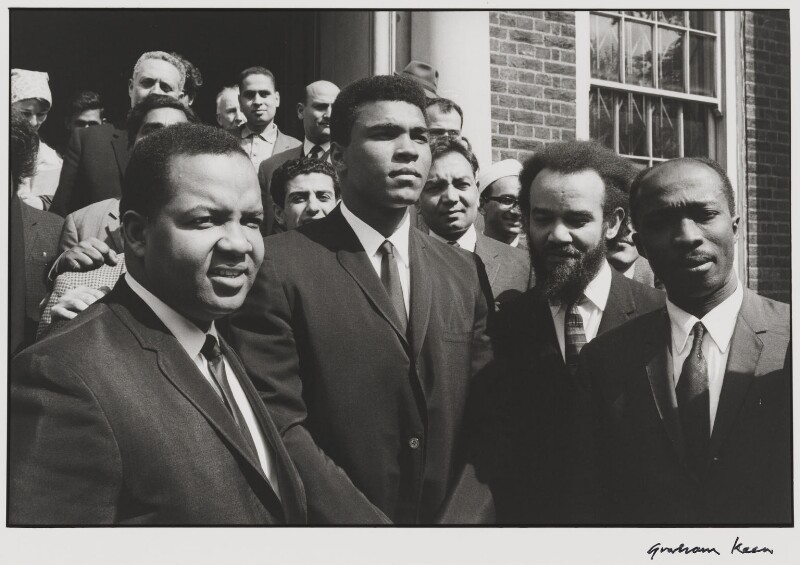

He gained support from international figures: John Lennon and Yoko Ono, Muhammad Ali, Jean-Paul Sartre—each seeing in Michael X a reflection of the global revolutionary moment. But inside the Black House, accusations of abuse began to pile up: authoritarianism, intimidation, financial misconduct.

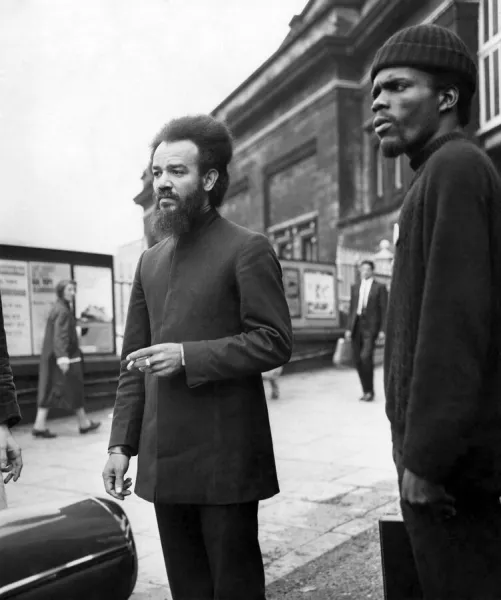

His rhetoric grew sharper. The cameras moved in. Scotland Yard got closer.

The 1967 trial for incitement to racial hatred marked a turning point. Michael X became the first man in Britain prosecuted under the new hate speech law. To his supporters, he was a pioneer of Black free speech. To his critics, a dangerous agitator.

In the press, he was alternately a prophet or a charlatan. In the streets, adored or reviled.

But most importantly, he had become visible. And that, in itself, was revolutionary.

III. The hunted man: Controversies, flight, and fall

A. Trials and scandals

Radical figures attract the spotlight—until it burns them.

By the late 1960s, Michael X was everywhere. He spoke boldly, denounced loudly, provoked constantly.

His public appearances were theatrical, his words razor-sharp. He embodied a new kind of Black British man: proudly African, fiercely anti-colonial, deliberately provocative.

But this visibility came at a cost.

In 1967, he was charged under the freshly passed Race Relations Act. The accusation: claiming that “Black people should kill white people to be free.” Context ignored. Tone omitted. Sentence delivered. To the white press, he became a caricature of a revolutionary. To the police, a textbook case.

The trial, heavily publicized, made him the first Briton convicted for inciting racial hatred. A historical irony: a law designed to protect minorities from racism was used to silence one of the few Black men publicly challenging colonial order.

The Black House, once a sanctuary, became a trap. Intelligence services watched. Internal divisions erupted. Some spoke of intimidation. Others of manipulation. One day, Michael placed a slave collar on a young white man’s neck—to symbolize role reversal. The media had a field day. Public opinion turned.

Cornered, Michael X fled.

B. Exile to trinidad and a deadly spiral

In 1970, he returned to Trinidad—back to where it all began. But he was no longer de Freitas the youth. He was a fugitive. A prophet in exile. There, he aimed to start over. He founded a new “Black House,” more mystical, more rural, nearly cult-like. He spoke of roots, self-sufficiency, elevation.

But the community grew insular. Tensions escalated. Paranoia set in.

In 1972, two bodies were found:

Gale Benson, a white British activist and partner of one of Michael’s close aides, buried alive.

Joseph Skerritt, a former associate, shot under unclear circumstances.

Michael X was arrested. The myth collapsed.

The trial was held in Port of Spain, capital of Trinidad and Tobago. This time, the headlines spoke not of activism but of cults, madness, blood. The revolutionary had become a criminal. In 1975, he was sentenced to death and hanged. Until the end, he denied ordering the murders.

But no one was listening anymore.

IV. Legacy, rumors, and fragmented memory

A. Activist or impostor?

Even today, Michael X’s name divides opinion.

To some, he was a charismatic opportunist riding the Black Power wave to gain personal influence. To others, a forgotten forerunner crushed by a system unwilling to see a Black man hold so much political and media power in Britain.

Figures like Darcus Howe and Stokely Carmichael recognized him as a brother in struggle—even if his journey was neither flawless nor linear. In his own way, he channeled the anger of a generation unwilling to remain silent, to blend in, or to politely ask for a seat at the table.

His former supporters—Lennon, Yoko Ono, Muhammad Ali—fell silent after his fall. The press relegated him to the margins. Yet some voices still defend the necessity of his words, if not his actions.

Because Michael X was never pure. He was a man of flesh and contradiction.

But in his chaos, he forced England to confront its colonial mirror.

B. A fictional character?

Michael X’s life is so dramatic it still haunts screens and pages.

In the film The Bank Job (2008), he’s portrayed as a dangerous man at the center of a conspiracy involving gangsters and secret services. Some claim he was used by MI6, others that he was closely watched by the CIA due to ties with radical Pan-Africanists.

But official archives remain classified until 2054.

Until then, we’re left navigating conflicting testimonies, revolutionary fantasies, and fragmented narratives. Michael X drifts between fallen activist and corrupted guru.

In books, he’s a chapter.

In Black British memory, a ghost.

In official history, an omission.

What do we do with a man like Michael X?

He fits no mold. Too unorthodox to be celebrated. Too significant to be erased. His destiny reveals the limits of our narratives, the fragility of our myths, the violence of postcolonial exiles.

Through him, a question arises:

How are Black heroes made? Under what conditions are they celebrated? And for which sins are they condemned to oblivion?

Michael X was neither angel nor monster. He was a man of his time—a time of fire and fracture.

His story—between Black revolution and Caribbean tragedy—deserves to be reread, not to absolve him, but to understand what it still means to be free, Black, and unacceptable.

Sources

- Michael X: Hustler, Revolutionary, Outlaw, The Floor Magazine, 2022

- Michael X and the Black House, BBC Archive

- Michael X, Wikipedia article

- Contemporary testimonies found in:

- Black Britain: A Photographic History, Paul Gilroy, 2007

- Voices of the Windrush Generation, David Matthews, 2018

Summary

- I. A Man of His Time: Between Exile and the Search for Identity

- A. Caribbean Roots and Turbulent Youth

- B. The Encounter with Malcolm X and the Birth of an Activist

- II. The Rise of Black Activism in the United Kingdom

- A. Britain’s Racial Landscape in the 1960s

- B. The Racial Adjustment Action Society and the Black House

- III. The Hunted Man: Controversies, Flight, and Fall

- A. Trials and Scandals

- B. Exile to Trinidad and a Deadly Spiral

- IV. Legacy, Rumors, and Fragmented Memory

- A. Activist or Impostor?

- B. A Fictional Character?

- Sources