On May 8, 1902, a pyroclastic flow destroyed Saint-Pierre in Martinique, killing 30,000 people. Only one man, a Black prisoner named Louis-Auguste Cyparis, survived. This is his story—caught between colonial erasure, American showmanship, and a searing legacy.

Louis-Auguste Cyparis: From the dungeon of Saint-Pierre to the world stage, story of a forgotten survivor

There are survivors who never return—not because they died, but because the world they knew has vanished. Louis-Auguste Cyparis, a prisoner from Martinique, was one of three survivors of the pyroclastic flow that, on May 8, 1902, annihilated Saint-Pierre and 30,000 souls. This is the story of a man who bore on his body the ashes of a submerged world.

At the turn of the 20th century, Saint-Pierre was the beating heart of Martinique. Nicknamed the “Little Paris of the Antilles,” the city shone with prestige: cathedral, theater, high school, international port. Everything exuded colonial prosperity, built on sugar wealth and the labor of freed slaves’ descendants. But in May 1902, a rumble from deep within Mount Pelée would wipe this capital off the map.

The volcano stirred slowly, almost insidiously. Signs of unrest multiplied, yet authorities dismissed them as just another “natural curiosity.” Maintaining public order and ensuring the second round of legislative elections were their only priorities. It was a historic act of recklessness.

In the shadows of this vibrant city lived Louis-Auguste Cyparis. Born Ludger Sylbaris in Le Prêcheur in 1874, he was a man of the people—a sailor and laborer. A drunken brawl led to his imprisonment. Days before the cataclysm, he was placed in solitary confinement for attempting to escape. A small, thick-walled, damp cell. His grave, so it was thought.

But it would become his concrete coffin—sealed against the wrath of the heavens.

On May 8, 1902, at 7:52 a.m., Mount Pelée unleashed hell. A pyroclastic flow—a searing mix of gas, ash, and rock—raced down the slope at over 500 km/h. Within two minutes, Saint-Pierre was incinerated. Bodies were frozen in postures of panic. Ships exploded in the harbor. Nothing remained. Or nearly nothing.

Three days later, rescue teams heard groans beneath the prison’s rubble. They discovered Cyparis, severely burned, barely clinging to life—but alive. He was saved. He was alone. He was the man death had forgotten.

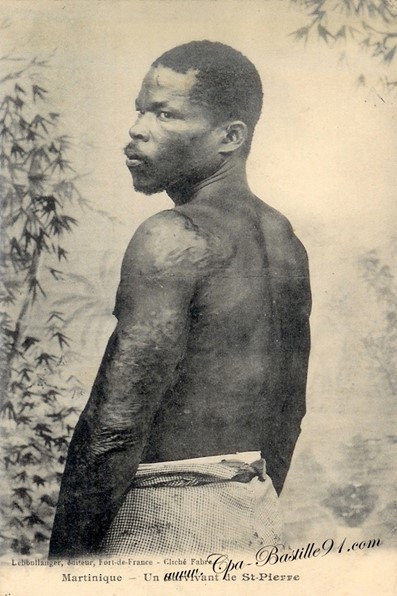

Pardoned, Cyparis soon became the center of attention. The United States quickly seized upon his story. He was recruited by Barnum’s circus, who saw in him a living attraction. “The man who lived through Doomsday,” the posters declared. The man who survived the Apocalypse. His back was laced with scars. His body became an exhibit—proof that hell had once existed.

Cyparis drifted through America like a ghost. He was photographed. Interviewed. Examined. But never truly heard.

Colonial history prefers uplifting tales. Heroes. Martyrs. But what to do with someone like Cyparis? Black, poor, an ex-convict. His survival owed only to a twist of carceral fate. He didn’t fight. He endured. And that was unsettling.

In history books, Mount Pelée is remembered more than those it spared. Death has its myths. Life has its debts.

In 1929, Cyparis died in Panama—alone, forgotten, destitute. He never found a home again. Not in Martinique, where his criminal past haunted him. Not in America, where he was a curiosity but never a citizen.

His name appears only marginally in accounts of the eruption. Yet his body was an archive. His memory, a scorched library.

What Cyparis carried was more than the story of a survivor. It was the story of a silenced people, whose endurance is etched into their flesh. He was a witness to a collapse—the downfall of a colonial world that believed itself invincible.

Through him, an entire era collapsed. Saint-Pierre wasn’t just destroyed by a volcano. It was swallowed by administrative arrogance, political blindness, and a refusal to listen to the voices of the people.

At the time of official commemorations, statues of Cyparis are rare. In Saint-Pierre, his cell has become a tourist site—but how many visitors understand what it represents? It’s not a disaster movie set. It’s a harsh reminder that history isn’t always written with the heroes we choose, but with those we discard.

Louis-Auguste Cyparis leaves us an uncomfortable legacy. Not one of miracles, but of disturbance. He forces us to reconsider the hierarchy of memory. He was not the hero colonial France wanted to celebrate. But he is the one whose existence cracks the dominant narratives.

He is the face of Black survival in a world that sought to erase it. He is a lesson in dignity. A fracture in the silence.

Sources

- Césaire Philémon, La Montagne Pelée et l’effroyable destruction de Saint-Pierre, 1930.

- Jean Hess, La catastrophe de la Martinique : notes d’un reporter, 1902.

- Charles Lambolez, Saint-Pierre – Martinique 1635-1902 : Annales des Antilles françaises, 1905.

- Maurice Krafft, Volcans et éruptions, Hachette, 1985.

- Denis Westercamp and Haroun Tazieff, Martinique – Guadeloupe: Regional Geological Guides, Masson, 1980.

Contents

- Louis-Auguste Cyparis: From the Dungeon of Saint-Pierre to the World Stage, Story of a Forgotten Survivor

- Sources