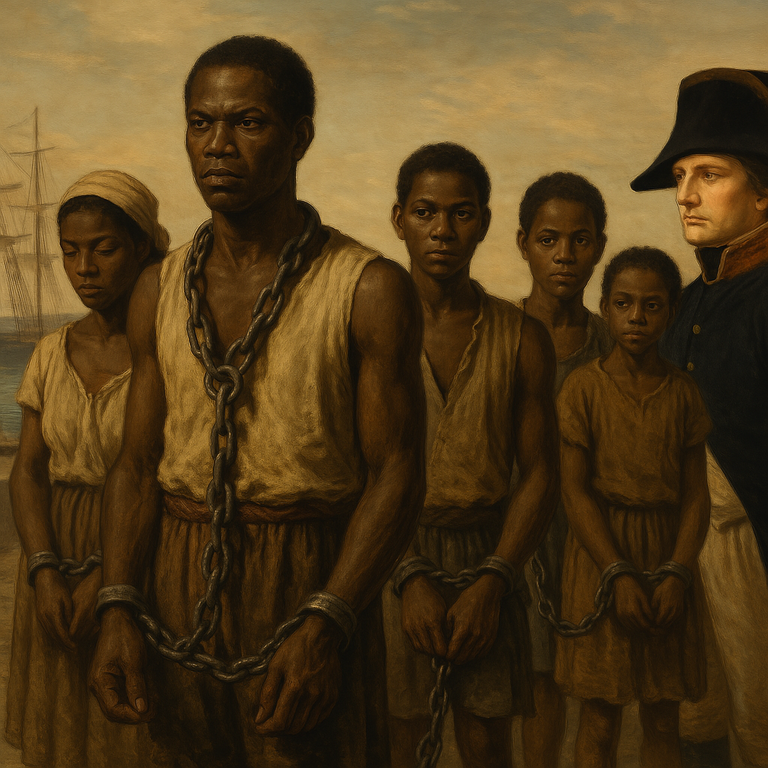

In 1802, under the orders of Napoleon Bonaparte, hundreds of Guadeloupeans and Haitians were torn from their homeland and forcibly sent to Corsica. Their crime? Refusing the return of slavery. Here is the overlooked story of a political and racial deportation that left a deep mark on the history of France, one of silence, suffering, and resilience.

I. The broken wind of freedom

The year 1802 could have consolidated the revolutionary achievements in the colonies. Instead, it marked the betrayal of hope. Eight years after the abolition of slavery proclaimed by the Convention in 1794, Napoleon Bonaparte, then First Consul, decided to reinstate the old order in the French colonies, notably in Guadeloupe and Saint-Domingue (Haiti).

But the former slaves, now citizens, soldiers, and free farmers, refused to once again become movable property. Their resistance was immediate, fierce, and heroic. In Saint-Domingue, Toussaint Louverture was deceitfully arrested and died at Fort de Joux. In Guadeloupe, the revolt led by Louis Delgrès was crushed in blood. And the survivors? For them, Napoleon had a solution as radical as it was cynical: deportation.

II. Deported in the name of freedom

Under the pretext of maintaining order, more than 400 Antillean men, women, and children — Guadeloupeans and Haitians alike — were torn from their native lands, chained, and sent to mainland France. First sorted in the penal colonies of Brest or Toulon, they were eventually sent to Corsica.

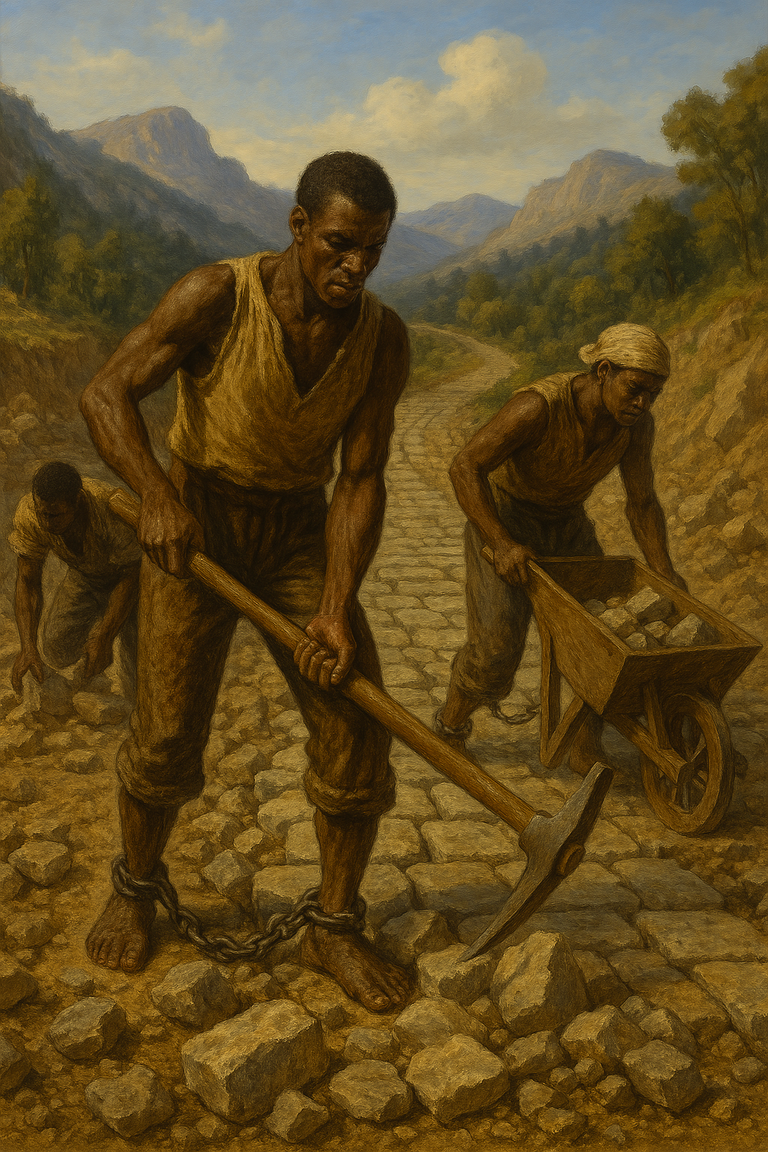

For Napoleon, Corsica was to be “civilized,” integrated into the French territory like any other colony. What better idea, he thought, than to assign these rebellious people from overseas to forced labor? The plan was not only punitive — it was ideological: to humiliate free Black people, to use them as tools of colonial development, and to crush their example.

III. The chains of oblivion

The deportees were interned in the Capuchin convent in Ajaccio, which had been turned into a camp. Stripped of their clothing, shackled, exposed to disease and the harsh climate, they were forced to take part in infrastructure work. Among these was the legendary road between Ajaccio and Bastia, in the heart of the Vizzavona forest. A “royal” road, built on the suffering of those the Republic had once called brothers.

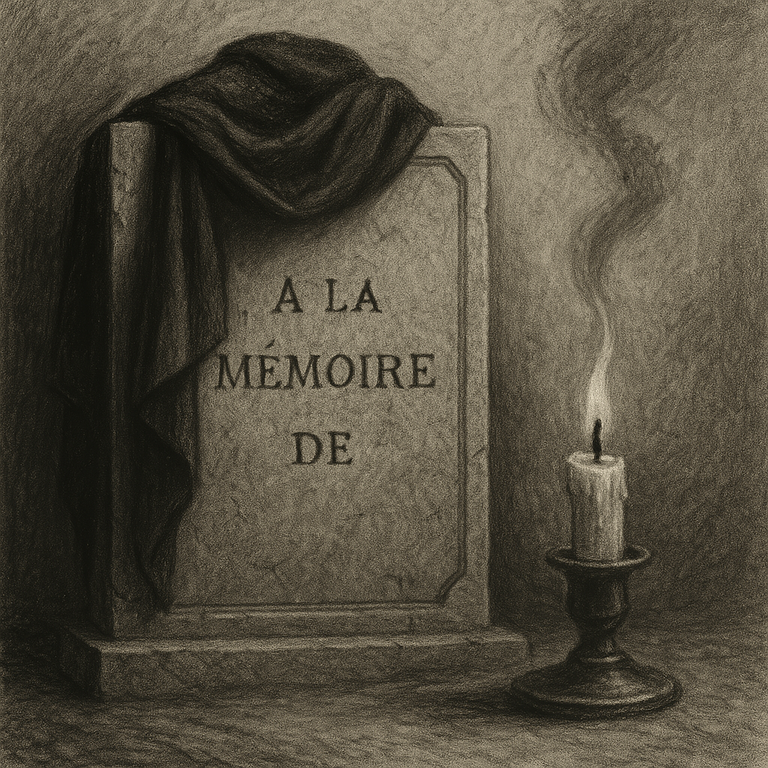

They felled trees, carved the slopes, and transported laricio pines to manufacture masts for the French navy. Many died of exhaustion, cold, and malnutrition. Few survived. Among them, Jean-Baptiste Mills, a mixed-race deputy, and Jean-Louis Annecy, a soldier and political figure, died far from their people, in oblivion.

IV. An erased memory

History has preserved neither their names nor their faces. For a long time, even historians ignored them. It was not until the 1990s, thanks to the work of researchers like Francis Arzalier, Bernard Gainot, and Claude Bonaparte Auguste, that this dark chapter began to surface. And even today, few places in Corsica or mainland France pay tribute to these men and women.

No national monument. No day of remembrance. Nothing but silence — inherited from the Empire and History — against a backdrop of the carefully maintained “Napoleonic legend.”

V. The invisible builders

And yet, without them, modern Corsica would not exist in its current form. The roads, bridges, forts, and trails of Vizzavona bear their mark. They were the first “Black builders” of insular France. They asked for neither gold nor status nor medals. Only to live free.

Their condition was not that of slaves, but of political enemies. Because they had challenged the established order. They had carried the ideal of freedom higher than the interests of the Empire. And for that, they were broken.

VI. Repairing history

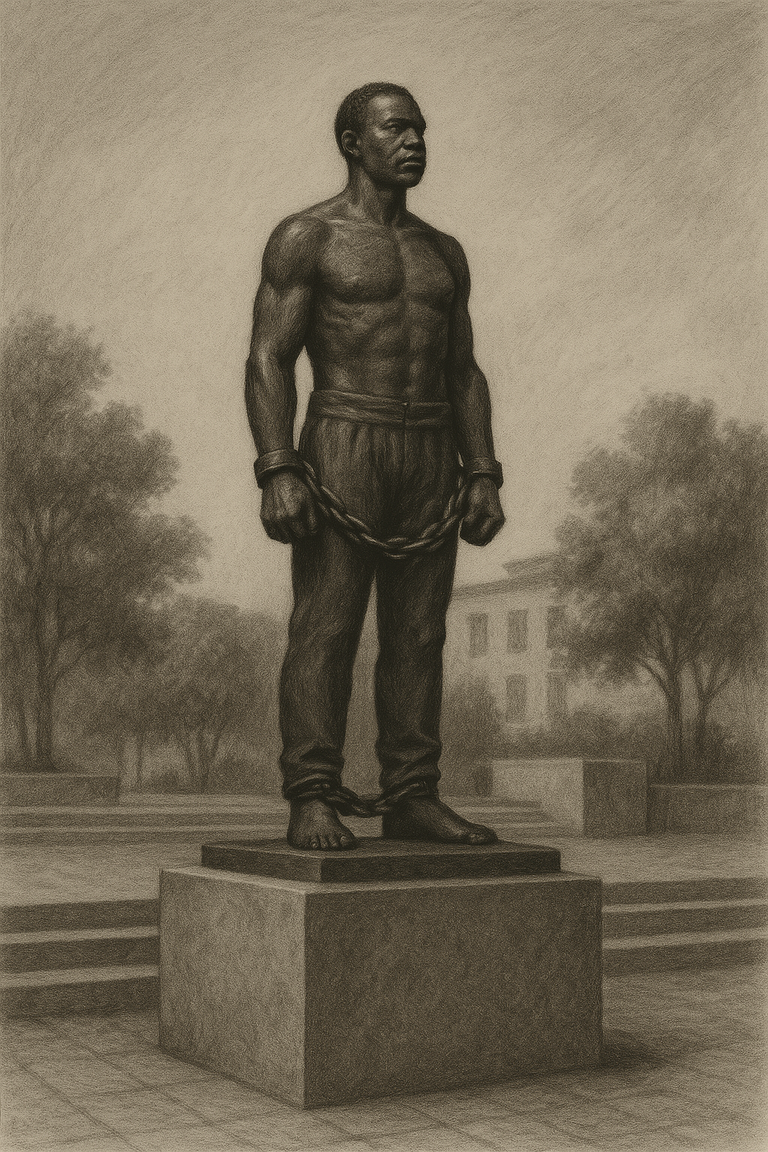

In 2022, historian Jean-Yves Coppolani proposed erecting a monument in Corte, in homage to the Antillean deportees. A welcome initiative — but still an isolated one. France, so quick to commemorate its glories, still struggles to acknowledge its betrayals.

Repairing history is not simply about building a stele. It is about teaching this memory in schools, mentioning it in museums, and engraving it into our collective consciousness. Because what these deportees faced — state racism, erasure, exploitation — still marks our present in other forms.

The Guadeloupeans and Haitians deported to Corsica were not passive victims. They were resisters. Their chains are not only instruments of submission: they are testimonies of dignity, courage, and struggle.

Bibliographic sources

- Francis Arzalier, Déportés haïtiens et guadeloupéens en Corse (1802–1814), Annales historiques de la Révolution française, nos. 293–294, Armand Colin / Société des études robespierristes, 1993, pp. 469–490.

- (ISSN 0003-4436; DOI: 10.3406/AHRF.1993.1586)

- Jean-Yves Coppolani, Des Antillais déportés en Corse à l’époque napoléonienne, Bulletin de la Société des sciences historiques et naturelles de la Corse, no. 656, 1989, pp. 245–254.

- Marcel Grandière, Les réfugiés et les déportés des Antilles à Nantes sous la Révolution, Bulletin de la Société d’histoire de la Guadeloupe, nos. 33–34, 3rd and 4th quarters of 1977.

- (Available at SHG Archives)

Table of contents

I. The Broken Wind of Freedom

II. Deported in the Name of Freedom

III. The Chains of Oblivion

IV. An Erased Memory

V. The Invisible Builders

VI. Repairing History