On May 20, 1802, Napoleon signed a law reinstating slavery in the colonies. A forgotten page of republican history, where liberty receded and chains returned. In stark contrast to the principles of 1794, this decree once again legalized the slave trade, servitude, and racial domination. A rupture that the Republic has never truly accounted for.

The day the republic betrayed its own principles

They had won their freedom at the tip of machetes. Etched it into scorched earth, in sweat and defiance. They hadn’t waited for Paris to liberate them—they had broken free themselves, fists raised, chains shattered, plantations set ablaze.

But on May 20, 1802, a pen dipped in the ink of power redrew the bars.

From the carpeted salons of the Consulate, a thousand leagues from the cane fields and lands of revolt, Napoleon Bonaparte (First Consul of the French Republic) passed a decree. A dry sentence slipped into a legal article:

“In the colonies returned to France, slavery shall be maintained in accordance with the laws and regulations in force before 1789.”

— Article 1 of the Law of 30 Floréal Year X (May 20, 1802)

This administrative formula struck like a death sentence for Black emancipation. It didn’t merely restore slavery. It re-legitimized a system, an economy, an ideology.

It authorized once again the trade of human beings.

It denied, wholesale, the hard-won victories of former slaves.

It reaffirmed the racial order as a foundation of the French colonial project.

And above all: it marked the absolute betrayal of the Republic’s founding principles.

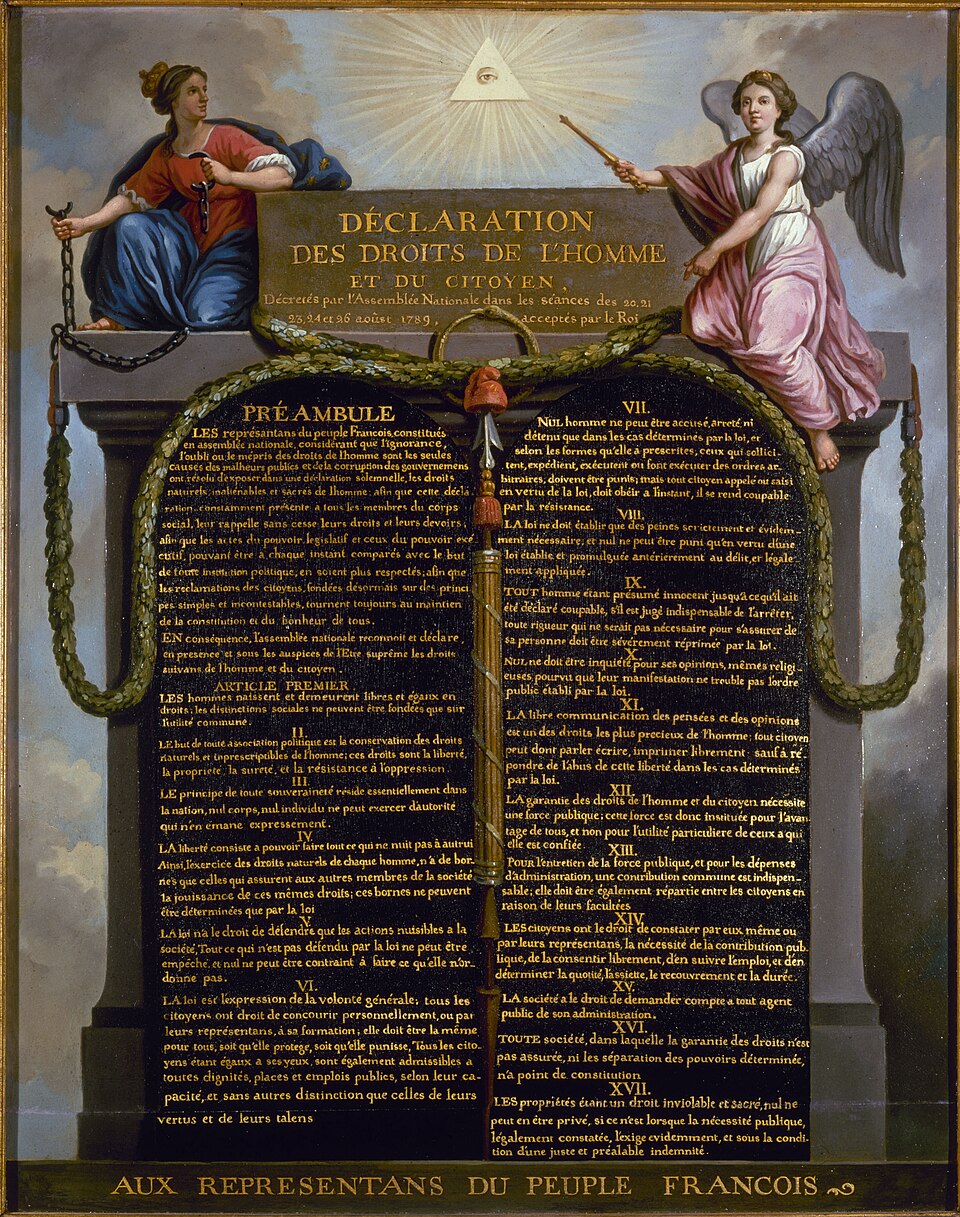

In 1794, the Convention had abolished slavery in the name of liberty,

- proclaiming all inhabitants of the French colonies full citizens,

- acknowledging (at least on paper) racial equality as a revolutionary truth.

But less than a decade later, the fear of Black freedom prevailed. The Republic, anxious about its margins, its uprisings, its “egalitarian excesses,” chose to restore colonial order.

This was not a misstep. Not a simple setback. It was a cold, calculated political decision—with heavy consequences.

A freedom too loud for the halls of power

The abolition of 16 Pluviôse Year II (February 4, 1794) had been a spark in a Revolution that claimed to break all chains. Proclaimed in Paris, it made all men (regardless of color) full French citizens. But in the colonies, freedom did not travel at the same speed as decrees.

- In Martinique, as early as 1793, royalist colonists preferred to hand the island over to the British rather than recognize the legitimacy of an egalitarian Republic. The Treaty of Whitehall even allowed them to preserve slavery under the British flag, with London’s consent.

- In Réunion, resistance was just as fierce: planters refused to enforce the revolutionary law and continued the slave trade as if nothing had changed.

- In Saint-Domingue, only force held sway: it was General Toussaint Louverture, former slave turned strategist, who enforced abolition by the sword—through negotiation, combat, and governance.

In truth, Black freedom had never truly been accepted by the colonial elite. It was tolerated in crisis, feared as soon as it became permanent.

And when Bonaparte returned to power in 1799, he saw this freedom as disorder to be extinguished.

To him, emancipation was neither a revolutionary gain nor a civilizational advance.

It was an obstacle. A threat. An anomaly.

What Napoleon feared was not equality—it was its spread.

- That free Black people might govern territories.

- That former slaves might control sugar production.

- That the principles of 1789 might challenge the Empire’s slave-based economy.

Because at its core, behind the decree of May 20, 1802, lay more than political cynicism. There was a worldview—orderly, hierarchical, colonial, and white. A vision in which the freedom of some disrupted the profits of others.

“I am for the whites because I am white.”

— Napoleon Bonaparte, Council of State, 1802

This statement was no slip—it was a doctrine. In one line, it encapsulated the racial foundation of the imperial project:

- whiteness as a criterion for legitimacy,

- presumed superiority as a political principle,

- and slavery as a tool of economic stability.

Faced with this, Black freedom became an unbearable noise. It disturbed social order, the sugar economy, imperial ambitions. So it was silenced. By decree. By cannon. By decree again.

But what had been won could no longer be unlearned. And in reinstating slavery, Bonaparte did not restore order—he sparked a war.

The law of 30 floréal year X: The text of an assumed regressione

On May 20, 1802, the Republic etched its shame into legal jargon.

The decree appeared in cold, technical form—as is often the case when violence is cloaked in the veneer of administration. Yet each article, read aloud, rang like a funeral bell for the hope born in the colonies eight years earlier.

Nofi presents the full transcription of the Law of 30 Floréal Year X (May 20, 1802), regarding the slave trade and the colonial regime:

IN THE NAME OF THE FRENCH PEOPLE, BONAPARTE, First Consul, PROCLAIMS as law of the Republic the following decree, passed by the Legislative Body on 30 Floréal Year X, in accordance with the proposal submitted by the government on the 27th of said month, and communicated to the Tribunate the same day.

DECREEArt. I In the colonies returned to France under the Treaty of Amiens¹, dated 6 Germinal Year X, slavery shall be maintained in accordance with the laws and regulations in force before 1789.

II. The same shall apply in other French colonies beyond the Cape of Good Hope.

III. The trade and importation of Black people into said colonies shall proceed in accordance with the laws and regulations in effect before 1789.

IV. Notwithstanding all prior laws, the regime of the colonies shall, for ten years, be subject to regulations issued by the Government.

Certified to be a true copy, by us, the President and Secretaries of the Legislative Body.

In Paris, 30 Floréal, Year X of the French Republic.

Signed Rabaut le jeune, President; Thiry, Bergier, Tupinier, Rigal, Secretaries.

LET this law be affixed with the seal of the State, published in the Bulletin of Laws, entered in the records of judicial and administrative authorities, and the Minister of Justice is charged with overseeing its publication.

In Paris, 10 Prairial, Year X of the Republic.

Signed BONAPARTE, First Consul.

Countersigned, Secretary of State, Hugues B. Maret.

Sealed with the seal of the State.

Approved by the Minister of Justice, signed Abrial.

Approved by the Minister of the Navy and Colonies for enforcement in the colonies.

No ambiguity. No transitional period. No exceptions.

This text brutally erased the law of February 4, 1794—the one that abolished slavery throughout French territory, including the colonies. It reversed not just a political gain but a universal principle: that no person can be property of another.

This law did not seek to restore peace. It aimed to reclaim control through legalized terror.

By granting the government ten years of unchecked colonial power, Bonaparte created a regime of exception—a state within the state—where colonists would have free rein to restore authority by any means:

- re-shackling the enslaved,

- reviving the trade,

- punishing those who had dared to believe in equality.

This was not just a moral betrayal. It was an economic and strategic project, reviving the idea that France’s wealth depended on sugar, coffee, cotton—and thus on Black blood.

It might seem like an opportunistic maneuver, a circumstantial decision in the post-revolutionary context. But that would downplay the ideological weight of this law.

It was deliberate: proposed by the government, passed by the legislature, sealed by Bonaparte himself.

It was designed to last: Article IV granted the executive ten years of absolute power over the colonies.

It was enforced with rigor: French armies were dispatched to the Antilles, Saint-Domingue, and Guyana to ensure its implementation—even if it meant killing, burning, and re-enslaving.

In 1791, it was said that the soil of France freed anyone who set foot on it. But in 1802, colonial soil was no longer France. The Republic had split into two regimes:

- one for the whites of the metropole, governed by the Rights of Man,

- the other for the Blacks of the colonies, ruled by laws of exploitation.

This racial, territorial, and legal divide set a historic precedent of the utmost gravity:

For the first (and only) time in its history, the French Republic legally reinstated slavery.

This was no anomaly. It was the logical outcome of an imperial power sacrificing universalism whenever colonial interests were threatened..

Saint-Domingue: The failure of a colonial restoration

In believing it could restore colonial order, France triggered the irreversible. The decree of May 20, 1802—meant to reinstate slavery and white domination in all colonies—collided with an unbreakable wall: the living memory of freedom.

In Saint-Domingue, that memory had a name: Toussaint Louverture. A self-taught general, former slave, and governor of the island. Since 1794, he had enforced the abolition of slavery—not through decrees, but through organization, discipline, and authority. The Republic had promised liberty? He had made it real.

- He distributed land.

- Restarted plantations without slavery.

- Negotiated as an equal with the metropole.

But for Bonaparte, Black authority had become intolerable. Saint-Domingue was no longer a colony—it was a counter-model. As early as 1801, Bonaparte sent an expedition of 40,000 men, commanded by General Leclerc, his own brother-in-law.

Official goal: restore republican order.

Real goal: crush Black autonomy.

Leclerc began by negotiating, promising continued freedom. But in the shadows, orders circulated: disarm the Blacks, imprison Louverture, reinstate the old regime.

The response was immediate, massive, inexorable. The population rose up. The Indigenous Army, composed of former slaves, went to war against the Republic.

The climate, tropical diseases, mass desertions—and most of all, the Haitian people’s determination—overcame the imperial machine. Even Leclerc eventually admitted in a letter to the Minister of the Navy:

“We must give up the idea of restoring slavery in Saint-Domingue.”

But it was too late. Louverture had been betrayed, captured, and deported to France, where he died in a freezing Jura prison. Yet his legacy endured. The struggle continued. After Leclerc’s death and the failure of repression, a new general, Jean-Jacques Dessalines, took up the torch.

- He unified the forces.

- He expelled the French permanently.

- And on January 1, 1804, in Gonaïves, he proclaimed: “Haiti is independent.”

The French Republic had tried to restore colonial order.

Instead, it provoked the birth of the first free Black republic in modern history.

The law of May 20, 1802, intended to restore bondage, became the birth certificate of Black sovereignty.

Not granted, but seized—forged, owned.

This sequence (decree, expedition, resistance, independence) remains one of the blind spots of French history.

- Never studied as a military failure.

- Never acknowledged as a post-colonial rupture.

- Rarely taught as a lesson in sovereignty.

And yet, it reversed the world order.

It proved that an enslaved people could not only free themselves but build a nation from the ruins of empire.

What France had tried to break, Haiti had proclaimed.

What the law tried to deny, the Haitian revolutionary fire etched into History.

A betrayal still too unknown

Some laws are remembered. Others are erased. The law of May 20, 1802—rarely mentioned, never commemorated—is one the official memory prefers to bury. Not out of forgetfulness. But because it disrupts the polished narrative of the French Republic, the one that claims to have always marched toward more liberty, equality, fraternity.

And yet, the text of 30 Floréal Year X marks an irrefutable fracture in republican history.

- It is the only time since 1789 that the French state legally reestablished a system of human bondage.

- It is the admission that proclaimed universalism applied only to those who fit within the white, metropolitan, dominant framework.

This law was no accident.

It was the product of a clear political choice: to preserve colonial economic order, at the cost of a moral regression of abyssal scale.

It revealed, at the heart of the imperial project, a fully assumed racial hierarchy—where Black freedom was only a variable to be adjusted.

History is not a linear tale of progress

We like to believe that History moves forward, corrects its wrongs, follows an irresistible path toward justice.

But May 20, 1802, stands to shatter that illusion.

That day, the Republic didn’t stumble—it stepped backward.

Deliberately.

It renounced its ideals.

It betrayed its principles.

It trampled its revolutionary promise—not in secret, but in the name of law.

And that’s what makes this date so disturbing:

- It reminds us that equality can be repealed by decree.

- That freedom can be conditional.

- That the Rights of Man have sometimes been privileges of empire.

Every May 10, we celebrate abolition.

But every May 20 should make us reflect:

- On how easily power can sacrifice Black lives for profit.

- On the State’s capacity to regress when colonial interests are at stake.

- On our collective refusal to confront the darker sides of our heritage.

History is not written only with dates.

It is written with silences, laws, and scars.

And as long as May 20, 1802, remains ignored—

it continues to bleed.

Table of contents

- The Day the Republic Betrayed Its Own Principles

- A Freedom Too Loud for the Halls of Power

- The Law of 30 Floréal Year X: The Text of an Assumed Regression

- Saint-Domingue: The Failure of a Colonial Restoration

- A Betrayal Still Too Unknown

- History Is Not a Linear Tale of Progress

Further reading

Founding texts

- Decree of 30 Floréal Year X (May 20, 1802)

- Decree of 16 Pluviôse Year II (February 4, 1794)

- Napoleon Bonaparte’s remarks at the Council of State (1802)

Major Historical Studies

- Yves Bénot, The French Revolution and the End of the Colonies, La Découverte, 1987

- Laurent Dubois, Avengers of the New World, Harvard University Press, 2004

- Florence Gauthier, Triumph and Death of Natural Rights in Revolution, PUF, 1992

- Marcel Dorigny (ed.), Slavery, Resistance, and Abolitions, CNMHE / Somogy, 2008

Footnote

¹ Treaty of Amiens (1802): A peace agreement signed between France and the United Kingdom after the Revolutionary Wars. It allowed France to recover certain colonies, including Martinique, which had remained under British rule since 1794. ↩︎