First Guadeloupean to enter Polytechnique, an unsung hero of World War I, Camille Mortenol embodies the colonial paradox: loyalty without recognition, excellence without legacy.

A silhouette in history’s shadow

Some names are engraved in gold letters on academy pediments. And then there are others, just as deserving, who slumber in the margins. Camille Mortenol belongs to the latter: a naval officer, born free of a formerly enslaved father, trained at Polytechnique, and strategist of Paris’s anti-aircraft defense during the Great War. For a long time, French history relegated him to a mere footnote. Yet through colonial storms, the detonations of racism, and the complicit silences of the Republic, he held firm.

His name is a beacon. A memory. A quiet act of defiance.

I. From africa uprooted to the conquered sea

In Pointe-à-Pitre, on the morning of November 29, 1859, a child is born—one long ignored by official history, whose life defies erasure. Sosthène Héliodore Camille Mortenol, son of two former slaves, is born into a Guadeloupe still steeped in the ashes of bondage. Slavery had been abolished just twelve years earlier. The island was still nursing the wounds left by centuries of chains and sugarcane.

His father, born in Africa around 1809, had been captured, deported, and reduced to a human commodity. In 1847, at the age of 38, he bought his own freedom for 2,400 francs—a gesture as painful as it was symbolic. To the colonial administration, he is said to have declared:

“You took me from the land of Africa to make me a slave. Give me back my freedom today.”

He then adopted a new name, forged in reclaimed dignity: Mortenol.

His mother, Julienne Toussaint, born in 1834 and a seamstress by trade, had also been enslaved. Together, they had three children: Eugène, Marie-Adèle, and Camille, the youngest. In their modest home, where poverty never silenced dignity, education became a tool for emancipation, and the memory of oppression a lever for ascension.

Camille stood out early on. A brilliant and quiet student, he displayed a precocious gift for mathematics and discipline. He studied at the Brothers of Ploërmel’s day school, then at the seminary in Basse-Terre, before catching the attention of Victor Schœlcher. The former architect of abolition saw his potential and supported him. Thanks to a scholarship, Camille crossed the ocean to the mainland—the land that preaches Liberty, Equality, Fraternity, but struggles to embody them for its overseas children.

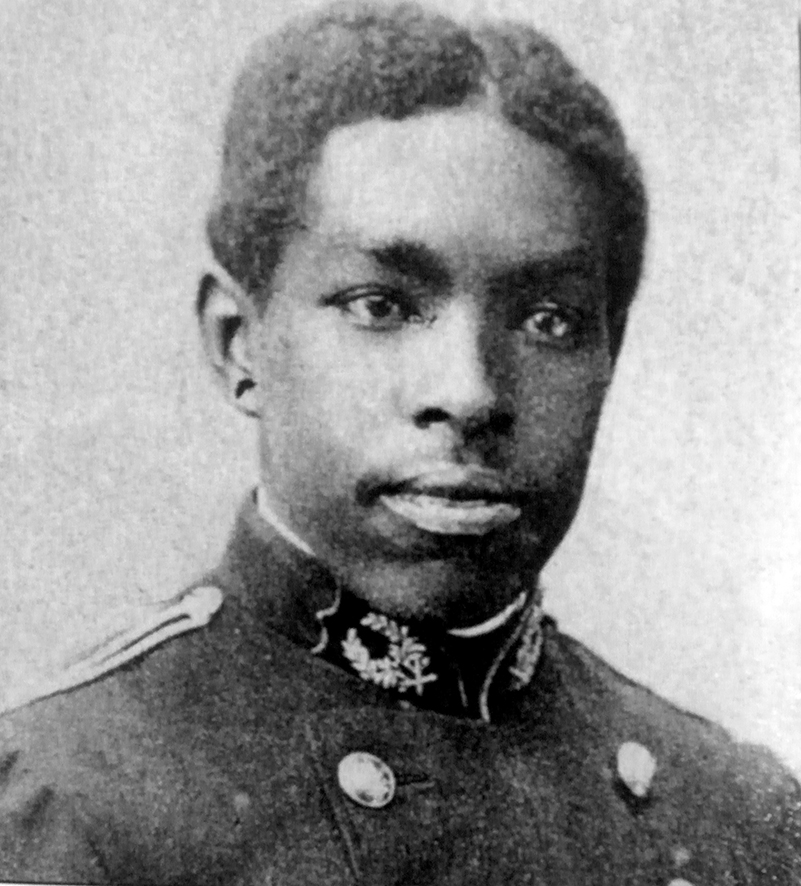

In Bordeaux, he enrolled at Lycée Montaigne to prepare for France’s elite university entrance exams. In 1880, he achieved the near-impossible: ranked 19th out of 209 candidates, he was admitted to the École Polytechnique. He thus became the first Guadeloupean, and only the third Black man, to enter the institution—after Auguste-François Perrinon (X 1832) and Charles Wilkinson (X 1849). On that day, in the history of France, the son of a slave walked through the gates of one of the most selective schools in the country.

But this success did not shield him from latent scorn. At Polytechnique, he was noticed—both for his talent and his skin color. During the hazing ritual known as the “séance des cotes,” he was given the “negro rating.” The humor was military, racist. Yet behind the condescension, his classmates acknowledged his worth. One even said:

“If you are Black, we are white; each has his color, and who can say which is better?”

Mortenol did not seek revenge. He rose above. He learned to walk the halls of the republican elite without bowing his head, to carry his past like an invisible banner. He understood that each success was not merely personal, but the legacy of a people, a memory, a story.

Graduating in 1882, 18th in his class, he chose the French Navy. A strategic decision. The army remained largely closed to officers of color, but the “Royale,” with its more technical hierarchy, left a door ajar. He joined as a midshipman aboard the frigate L’Alceste. A century after his father was torn from Africa by the sea, the son now sailed its waves—not as human cargo, but as an officer of the French Republic.

II. Crossing the color lines

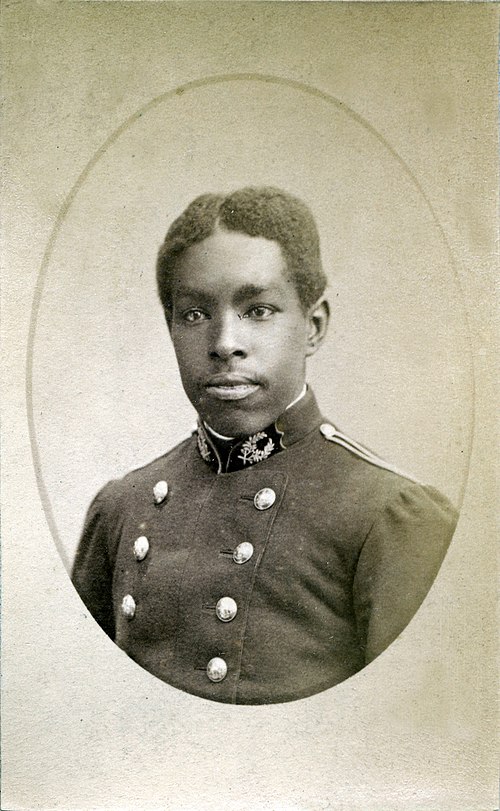

Upon graduating from Polytechnique in 1882, Mortenol made a decision both symbolic and strategic: he joined the French Navy—then known as “la Royale,” a bastion of republican aristocracy, where wearing the uniform came with an unspoken color code: white by default. On the decks of French ships, the Republic flew high, but fraternity remained docked ashore.

He first embarked on the sailing frigate L’Alceste. Soon, his career took off. Madagascar, Indochina, West Africa, the Mediterranean, the Levant—Mortenol sailed wherever the Empire cast its colonial ambitions. He was not just an officer, but a face of French power, commanding units and operating in conflict zones, often on the front line. The absolute paradox: the son of an African slave became an agent of imperial expansion on the very continent from which his father had been torn.

His rise was steady, well-earned, but never easy. He was promoted ensign in 1884, lieutenant in 1889, and frigate captain in 1904. Each step up came from faultless service, grueling campaigns, and successful missions. Yet, behind the medals, internal reports from his superiors hinted at “potential issues due to his race.” On the docks of Toulon, Brest, or Saigon, passersby turned heads. Some sailors—even fellow officers—whispered: “A Black man, a captain?”

He endured. He advanced. He commanded.

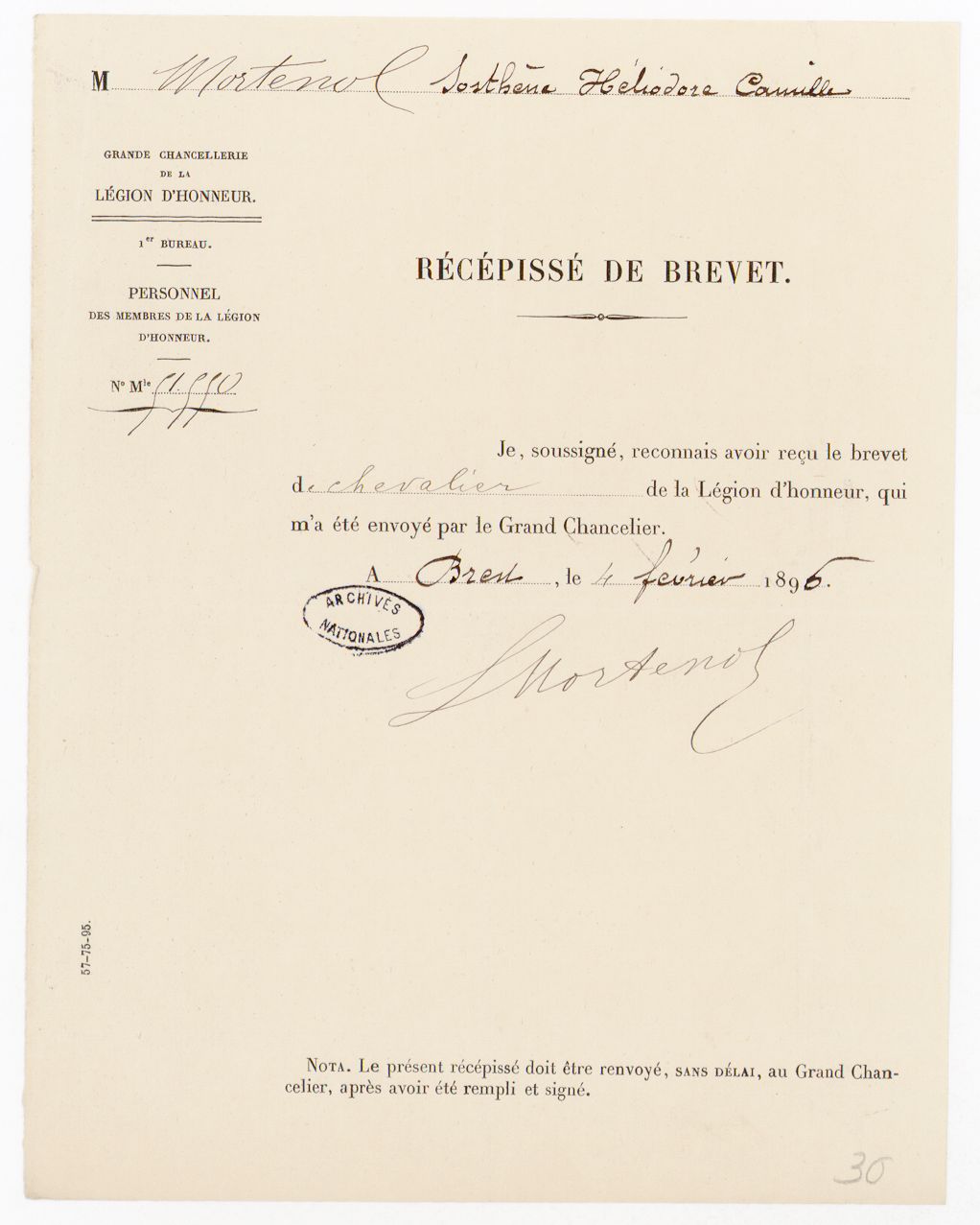

In 1895, he joined the Madagascar campaign under General Gallieni. He led critical military operations in places like Marovoay and Maevatanana, where Malagasy resistance to French domination was fierce. His valor earned him the Legion of Honor, awarded personally by President Félix Faure. A photograph captures the moment: a Black officer decorated for conquering a Black land in France’s name. A dizzying loop.

But medals could not shield him from racism. One commander noted in a report:

“Mortenol is an excellent officer. The only thing that might hinder him is his race, and I fear it is incompatible with high-ranking positions in the Navy.”

In the ink of bureaucracy, color trumped merit. His track record was not enough. He had to be flawless just to be accepted.

In 1902, he married Marie-Louise Vitalo, a widow from Cayenne, whom he met in Paris. They had no children, but shared a quiet home. She died ten years later in Brest, where Mortenol was stationed. He never remarried. His life was that of a solitary man, devoted to service.

For two decades, Mortenol commanded torpedo boats, led warships, and suppressed uprisings in Central Africa. In every port he set foot in, he was the Black exception in a world of white conformity. He represented the Republic, yet remained a foreign body within its system.

Still, he endured. Out of rigor. Out of honor. Driven by a deep intuition that his success was not his alone: it was a crack in the wall of exclusion—one others might later widen..

III. A colonized man commanding a capital at war

When World War I broke out in 1914, Mortenol was 55. To the military high command, he was too old to command a major battleship. Too seasoned to be idle. But perhaps above all (though no one dared say it), too Black for wartime naval command.

He was not one to fade into the background. He asked to serve—again. With support from General Gallieni, whom he had served with in Madagascar, he was assigned a crucial role: to head the Aerial Defense (DCA) of the entrenched camp of Paris. This role—essential, but still in its infancy—involved protecting the capital from aerial bombardment, a new threat at the time, posed by Zeppelins and early German aircraft.

The challenge was massive. When he arrived, Paris’s air defenses were rudimentary, almost non-existent. Anti-aircraft guns were rare, outdated, unable to aim vertically. The searchlights were weak, the communications unreliable. The City of Light was about to face the dark night of enemy raids—with little more than candles.

But Mortenol was no showman. He was a strategist. A silent builder. He inspected, calculated, reformed.

In just a few months, he transformed Paris’s DCA into an aerial fortress. The guns were modernized, the searchlights multiplied, communication lines reinforced. He set up a watch network, organized rotations, optimized logistics. All without boast or spectacle. He built an invisible shield between bombs and civilians.

On March 21, 1915, Zeppelins flew over Paris. Mortenol was already at his post. The batteries he had installed opened fire. That day, bullets sliced through the sky with the determination of a man once deemed illegitimate.

By 1918, when the armistice was signed, Mortenol commanded 10,000 men, nearly 200 anti-aircraft guns, and 65 high-powered searchlights. In four years, he had turned a minor role into a central pillar of national defense. He held Paris—literally—beneath a protective dome of his own design.

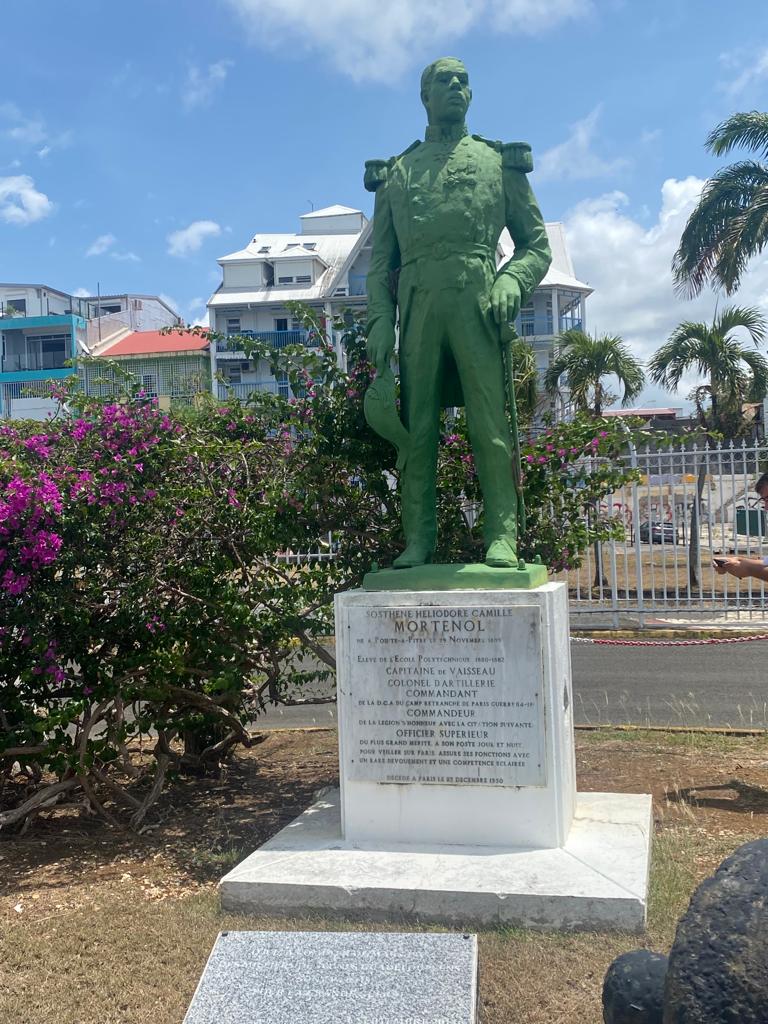

Yet his face never graced a poster. His name wasn’t etched into any monument. No statue at the Invalides. No street in a posh arrondissement. Barely a line in military textbooks.

He was thanked. Then erased.

Appointed colonel in the army reserves, he was made Commander of the Legion of Honor in 1920—without ceremony, without speech. The honors were discreet, almost whispered. The official story remained silent.

And yet, in the newspapers of the time, in soldiers’ memoirs, in letters from his men, Mortenol’s name recurs. Always with the same adjectives: methodical, effective, dignified, unyielding.

Camille Mortenol held Paris. But Paris did not hold onto him.

IV. An ungrateful France faces Its own heroes

In 1920, Camille Mortenol was made Commander of the Legion of Honor. A belated recognition—as if the Republic had waited for the war’s end to quietly acknowledge the man who, in the shadows, had protected Paris. He was never promoted to admiral. Not even general. He gave everything to France, but the Republic never gave him his full due.

No street bore his name in Paris during his lifetime. No plaque marks the places he guarded, planned, protected. No textbook mentions his pivotal role in the capital’s aerial defense. No national commemoration lists him among the heroes of the Great War. Camille Mortenol remains the forgotten author of a history written in bold ink.

And yet, in his private letters, in the modesty of his silences, one senses a wounded pride, a bruised dignity—but never submission. He never protested. Never shouted. He acted. He could have denounced, demanded, exposed the hypocrisy of a system that used him but never embraced him. He did not. Perhaps out of loyalty. Perhaps strategy. Perhaps because, to him, truth lay in deeds, not cries.

Mortenol belonged to a sacrificed generation of the Empire—Black, mixed-race, Indian, Malagasy, Indochinese men who wore the French uniform with honor, but never gained its full equality. They defended a country that never fully accepted them. They are the forgotten backbone of colonial France.

In 1930, Mortenol died in Paris’s 15th arrondissement, aged 71. He lies in Vaugirard Cemetery—far from the Invalides, far from the Panthéon, in a silence akin to erasure.

His wife, Marie-Louise Vitalo, born in Cayenne, preceded him in death in 1912. They had no children. No heir to carry his name. But his legacy endures. In military archives, in the defense maps he drew around Paris, in the too-muted memory of the Antilles, in the belated and sometimes uneasy tributes from a Republic still unsure how to honor all its sons equally.

Camille Mortenol died twice. Once in 1930. Again in the oblivion of national memory.

What Mortenol says about France

Mortenol is a history lesson. A fracture. A mirror. He is the story of a Black man in a country that champions universalism but struggles to recognize its own children when they fall outside expected lines.

He is also proof that Black excellence has always existed—even when denied. The goal is not to essentialize Mortenol, nor turn him into a mere “role model.” It is to understand what he reveals about French social order, its hypocrisies, and its chosen silences.

Should he be enshrined in the Panthéon? Perhaps. But first, his name must be taught in classrooms, included in official narratives, shelved in Republic libraries.

Mortenol is us.

Camille Mortenol is not merely a Black officer of the Third Republic. He is a page of France that someone tried to fold over. A reminder that History—the one we teach children—must be written in many voices.

In every Antillean child, every African or Afro-descendant student who questions their place, there echoes Mortenol. An invitation to hold firm. Not to settle for tolerance. But to claim one’s place through knowledge, discipline, and courage.

Yes, France was defended by the son of a slave.

And it is time for France to remember.

Table of contents

- A Silhouette in History’s Shadow

- I. From Africa Uprooted to the Conquered Sea

- II. Crossing the Color Lines

- III. A Colonized Man Commanding a Capital at War

- IV. An Ungrateful France Faces Its Own Heroes

- What Mortenol Says About France