At the crossroads of Sufi mysticism and political strategy, Usman dan Fodio built the largest Islamic state in sub-Saharan Africa during the 19th century. A poet, educator, and revolutionary, he embodied a radical vision of social justice, religious reform, and governance through knowledge. This is the fascinating story of a man whom colonial history tried to erase, but whose name Africa has never ceased to whisper.

The forgotten epic of the great black caliph

On April 20, 1817, in the city of Sokoto, died a man whom colonial history methodically erased from memory: Usman dan Fodio—mystical poet, Islamic reformer, military strategist, and founder of the largest precolonial state in West Africa. He is among those figures that contemporary Africa rediscovers with astonishment, as his journey defies established categories: a radical intellectual and war leader, a defender of knowledge and bearer of the sword, architect of a theocratic state and social visionary.

In the shadow of colonial arrogance, the legend of the Shehu (as his heirs still call him) was passed down in silence. Yet, from Sokoto to N’Djamena, from the Sahel to the Maghreb, his name resonates in Sufi brotherhoods, royal genealogies, and the stories elders whisper by the fire. This is the rarely told story of the man who dared to found an empire under the banner of God and knowledge alone.

The light from Fouta

At the dawn of the 18th century, on the fringes of the Hausa kingdoms between savannah and Sahel, a light rises. It comes not from a palace or a throne, but from a small village named Maratta, lost in the plains of Gobir—one of the most powerful city-states in northern present-day Nigeria. There, in December 1754, Usman is born, son of Muhammad Fodio and Hauwa bint Muhammad.

He bears only his father’s name, but history already designates him with a title: Shehu, the master.

Usman’s family belongs to the Torodbe (sometimes called Toronkawa or Torobe), a group of itinerant Fulani scholars originating from Fouta Toro, on the banks of the Senegal River. Migrating since the 14th century into the heart of Africa, these scholars established centers of knowledge in Hausa lands, integrating the language and customs while preserving science as their heritage.

These scholars formed a non-noble yet influential elite, respected for their erudition, mastery of Islamic law, and ability to transmit knowledge. They were the teachers of kings, judges of markets, and poets of the people. Among the Torodbe, blood held value only when mixed with ink.

Usman is born into a modest home saturated with books. His father is a renowned Maliki jurist, and his mother, Hauwa, reportedly a descendant of the Prophet Muhammad, comes from a lineage of learned women. Her own mother, Ruqayyah bint Alim, was a revered ascetic and author of the mystical work Alkarim Yaqbal, read generations later.

In the Fodio household, women were not relegated to the kitchen: they taught, debated, and wrote.

It is Hauwa, his mother, who teaches him to read the Qur’an, to reason, and to observe. She instills in him moral rigor, religious fervor, and a taste for discipline. Later, he completes his education under regional masters, including the charismatic Jibril ibn Umar, a passionate reformer from the south who profoundly influences his thought, despite later disagreements.

By age seven, Usman has mastered the Qur’an. At fifteen, he begins studying fiqh (Islamic jurisprudence), usul al-din (foundations of faith), Arabic grammar, and logic. By twenty, he is recognized as a mallam, a master, and establishes his school in the village of Degel.

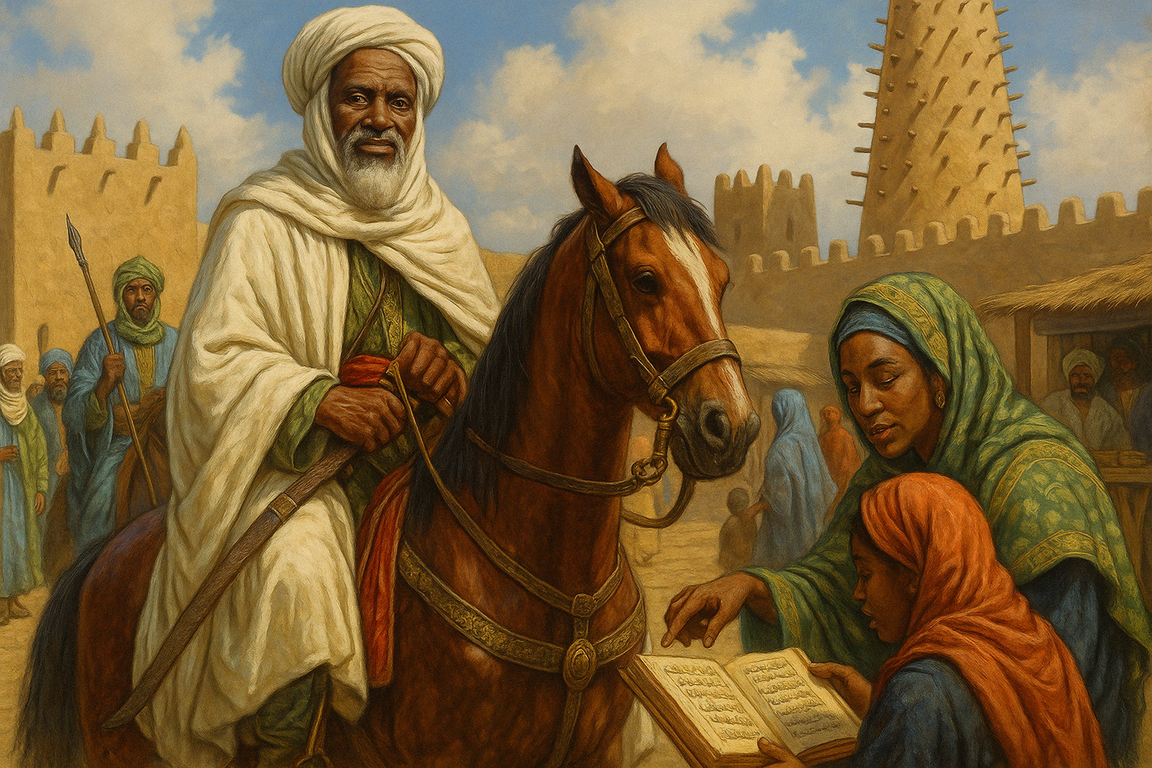

Degel quickly becomes a center of intellectual influence: students, scholars, and simple peasants come to listen to this lean man with a piercing gaze, dressed in coarse wool, preaching a pure, socially engaged, and mystically profound Islam. He already composes Fulfulde poems, writes in Arabic, and debates with court ulama.

In a society dominated by kingdoms where religion often serves as a facade for tyranny, Usman opposes the authority of knowledge to that of the sword, living faith to superficial religion, and spiritual reform to royal opulence.

A poet confronting kings

Before wielding the sword, Usman dan Fodio took up the pen. In a world where monarchs imposed their will through swords and chains, he chose words to challenge the powerful. He was neither a soldier nor a politician. He was a poet. A scholar. A rebel of the spirit.

His voice carried far. He wrote in classical Arabic, the language of scholars; in Hausa, the language of the people; and in Fulfulde, the language of his Fulani ancestors. Each word weighed, each verse inspired, carried an explosive charge against inequality and the hypocrisy of power.

Over a hundred works. Nearly five hundred poems. Treatises on law (fiqh), social manifestos, governance manuals, literary critiques, mystical commentaries. Usman dan Fodio’s work transcends religious frameworks: it is a true encyclopedia of African Islamic reform.

His most famous treatise, Ihyā’ al-sunna wa ikhmād al-bid’a (“The Revival of the Sunna and the Extinction of Blameworthy Innovation”), is a scathing critique of the Hausa religious elite. He denounces the “court scholars” who have sold themselves to kings, those who legitimize oppression with twisted legal arguments, those who turn a blind eye to sacrifices to spirits, unjust taxes, and debauchery masked under the veil of Islam.

He proclaims loudly:

“Religion is not an ornament for the throne. It is the throne itself.”

In his texts and sermons, the Shehu is uncompromising. He condemns:

- The excessive taxation imposed on peasants;

- The confiscation of land by chiefs;

- Unjustified slavery, especially of Muslims;

- Rigged trials, bribes, and the arbitrariness of royal judges.

He criticizes lavish feasts, public dances, and the mingling of men and women at ceremonies—not out of puritanism, but from a desire to align society with a moral, egalitarian, and spiritual ideal.

To him, sharia is not tyranny but a social charter of justice, a bulwark against abuse and moral decay.

What truly sets him apart from other reformers is his ability to link faith and society, to conceive Islam not as a rigid dogma but as a lever for liberating the oppressed.

While his contemporaries assigned women only the roles of wife or mother, Usman dan Fodio opened the doors of knowledge to girls as much as to boys.

“Ignorance is a prison, and a woman has no more place in it than a man,” he wrote.

He educates his daughters as he does his sons. The most famous, Nana Asma’u, becomes a major figure in Islamic feminist thought. She composes in Hausa, Fulfulde, and Arabic. She translates her father’s works, initiates hundreds of women into theology, and creates a network of female educators called the yan taru, who travel the caliphate to instruct village women.

Through her, the Shehu makes women’s education not a symbolic gesture but a central reform in his worldview.

In a context where Hausa kings saw women as property and scholars as tools of power, this stance is revolutionary.

Usman dan Fodio never called for war in his early writings. But his words were invisible swords. His sermons galvanized the poor, his writings circulated clandestinely, and his ideas undermined the legitimacy of rulers.

At heart, he proposed a new social contract:

- Power founded not on birth but on virtue.

- Governance oriented toward the common good.

- A society governed by divine justice, not human will.

This was too much for the kings. The Shehu, this wool-clad preacher turned spiritual leader of thousands, represented a danger far greater than a thousand soldiers. They would soon seek to silence him. Permanently.

From words to the sword

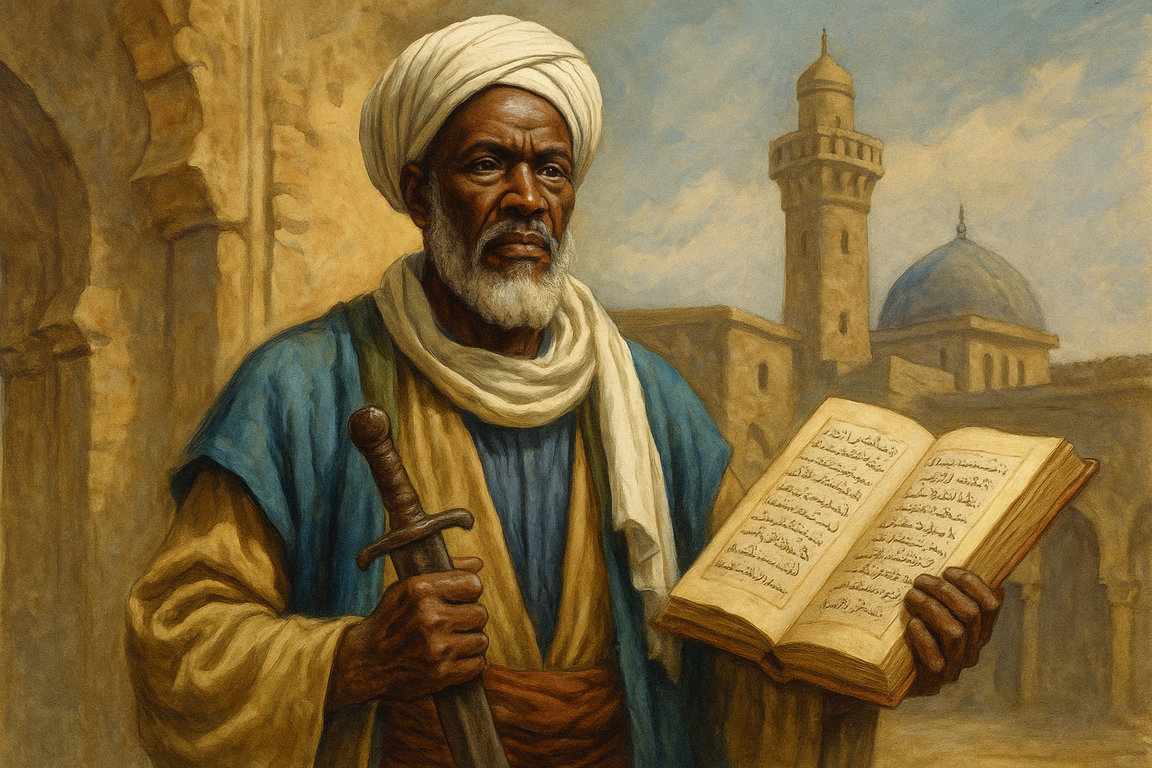

There are moments when words are no longer enough. When faith, to survive, must don leather and steel. For Usman dan Fodio, this moment comes in 1804—the year when the former disciple becomes a traitor, and the peaceful scholar becomes a war leader despite himself.

Yunfa, sultan of Gobir, is a tragic figure. Once a student of Usman dan Fodio, fascinated by his knowledge and captivated by his piety, he grows fearful as the Shehu’s influence expands. He sees in him a threat to the throne—a man who, without an army or wealth, already governs hearts.

As dan Fodio’s social and religious reforms begin to fracture the established order, Yunfa becomes afraid. He tries to silence him, then to break him, and finally attempts to kill him. The failed assassination is the spark. The Shehu realizes that the time for sermons is over. That injustice does not retreat before truth but before force. That tyrants yield only to the sword.

On February 20, 1804, Usman leaves Degel with his disciples, children, books, and a few belongings. It is a flight, but also a sacred act: the Hijra.

Like the Prophet Muhammad leaving Mecca for Medina, the Shehu emigrates to Gudu, on the kingdom’s edge. He is not alone: hundreds of followers accompany him. Others join along the way. A procession of men, women, children, scribes, and aspiring warriors—a community on the move.

In the sands of Gudu, far from royal power, the people proclaim him Amir al-Mu’minin, Commander of the Faithful. A declaration more political than religious. This title marks a rupture: the Shehu is no longer just a preacher; he is a head of state.

But this “jihad” is nothing like a stereotypical crusade. It is not a war to convert by the sword. It is an uprising of the marginalized, the humiliated, the invisible.

Around the Shehu gather:

- Nomadic Fulani, despoiled by the kings’ unjust taxes;

- Hausa peasants, crushed by taxes and famine;

- Northern Tuaregs, seeking a just order;

- Women, educated by the Shehu, active in resistance;

- Freed slaves, for whom the revolution is deliverance.

It is an army of faith, but also an army of the people. Poorly equipped, but ignited by an ideal: to establish an order based on justice, knowledge, and piety.

On June 21, 1804, the first major battle takes place at Tabkin Kwotto, near the lake of the same name. The caliphate’s troops are few, poorly armed, and possess only a handful of horses. Facing them, Yunfa has assembled a heterogeneous yet better-equipped force composed of Gobirawa cavalry, conscripted Tuaregs, and chiefs still loyal to the crown.

But it is the hills, the marshes, and their faith that give the advantage to the insurgents. Usman himself does not fight—he is too old—but his brother Abdullahi and his son Muhammad Bello lead the charge. The victory is total. The king flees, humiliated.

Then comes Matankari. Then Kebbi. Then Gwandu. The cities fall one after the other—not to brute force, but to the religious and social legitimacy the Shehu embodies. In every city taken, he does not impose domination but restores justice.

Each victory sends a message:

The old order is dead. The time of the just has arrived.

The rupture of 1804 is not just political. It is a rebirth. Islam is redefined as a social force, not a mere ritual. Authority becomes a contract, not an inherited right. Power is entrusted to a scholar, a mystic, a poet.

And Africa, silently, enters one of its greatest precolonial intellectual and political movements.

Sokoto, or the dream of a just state

It is not an empire that the Shehu builds. It is an idea.

A political, social, and spiritual vision: that of a state governed not by the sword, but by principles. A caliphate founded not on conquest, but on reform. A utopia realized: the Sokoto Caliphate.

Barely had the war ended when Usman dan Fodio renounced temporal power. He refused pompous titles, shunned palaces, and declined riches. He settled in Sokoto—not in the city center, but on its outskirts, in a modest adobe house.

He governed from the shadows, through counsel and example.

He appointed his son, Muhammad Bello, administrative Caliph of the East, and his brother, Abdullahi, governor of the West. Power was shared. Authority flowed. Intelligence prevailed over inheritance.

As for the Shehu, he devoted himself to what he considered his ultimate mission: teaching, writing, and shaping minds. Even as caliph, he remained until his death a teacher, a Sufi, and a poet.

The Sokoto Caliphate was not a theocratic state in the authoritarian sense. It was a society governed by sharia—but sharia applied as a tool of social justice, not as a mechanism of control.

- Qadis (judges) were appointed in every province to settle disputes according to Maliki jurisprudence.

- Markets were regulated by public inspectors charged with ensuring fair pricing, weight, and product quality.

- The Bayt al-Mal, or public treasury, was funded by zakat (obligatory alms), commercial taxes, and voluntary donations. These funds were redistributed to:

- orphans,

- the sick,

- travelers,

- teachers,

- students,

- widows,

- and deserving civil servants.

No tax was collected without moral justification. Wealth was not hoarded but redistributed. Usury was forbidden. Manual labor was honored. Idleness was banned.

The Sokoto Caliphate was more than a territory—it was a civilization.

A flourishing of knowledge, poetry, and education.

- Madrassas (schools) were established in both cities and villages.

- Traveling libraries carried the Shehu’s writings and those of his disciples throughout the caliphate.

- Women were educated, informed, empowered.

- Nana Asma’u developed a network of female teachers (Yan Taru) who went from village to village to teach rural women literacy and theology.

Writing was everywhere. In Arabic. In Hausa. In Fulfulde.

They wrote, translated, sang, and taught. The caliphate became a pan-African cultural center before its time—where the learned traditions of Al-Andalus, the Maghreb, Fouta, and the Sudan converged.

In less than a decade, the Sokoto Caliphate stretched over more than one million square kilometers:

- To the north: up to the edges of the Niger River and Tuareg desert.

- To the east: reaching present-day northern Cameroon.

- To the south: deep into Hausa and Nupe regions.

- To the west: to the gates of present-day Burkina Faso.

It was the largest precolonial state in West Africa.

But more importantly, it was a model. Other movements drew inspiration from it:

- the Massina of Seku Amadu in Mali,

- the Toucouleur Empire of Omar Tall,

- the reforms of Fouta Djallon and Fouta Toro.

The Shehu’s name spread through Sufi circles, courtrooms, and schools. It became a reference. An authority. A moral compass.

The light beneath the ashes

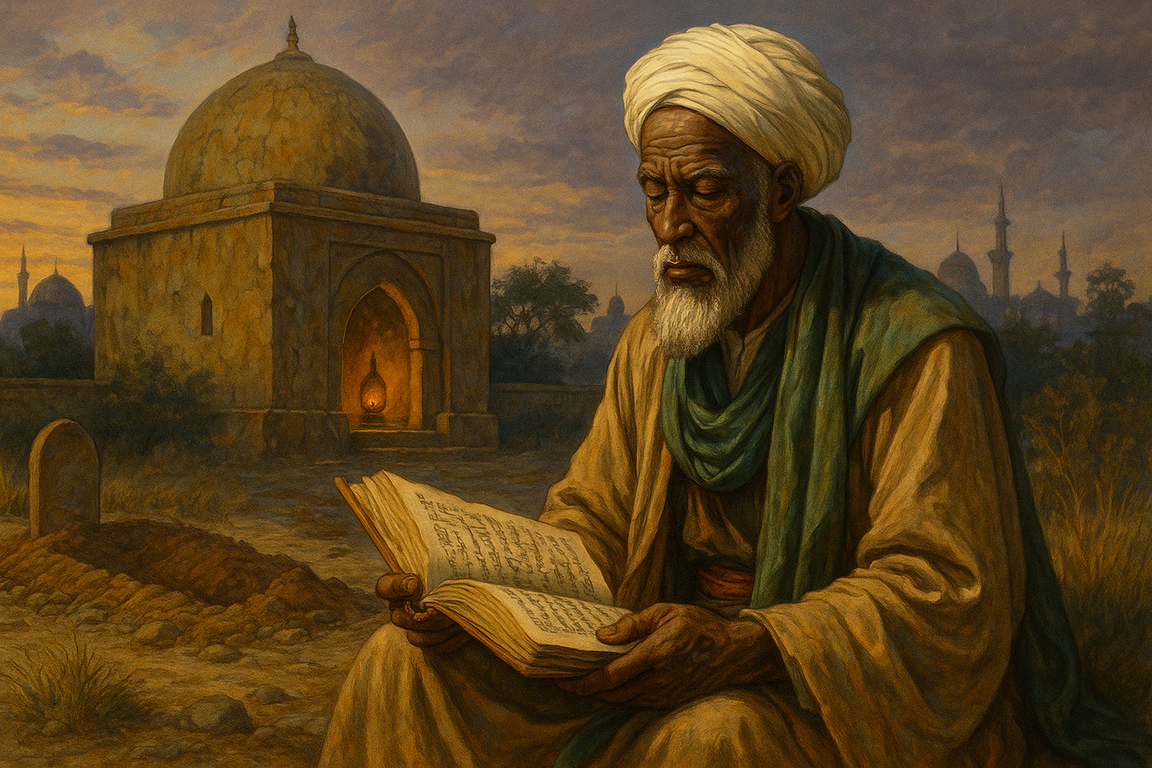

On April 20, 1817, Usman dan Fodio died in Sokoto at the age of 62.

No imperial procession. No golden mausoleum. Just a modest grave in a sanctuary turned pilgrimage site: the Hubbare Shehu—simple and sacred.

He left behind much more than an empire.

He bequeathed a vision, a legacy, an idea:

That Africa could be governed by justice, not by force.

That religion could liberate, not enslave.

That knowledge could structure a state, not serve demagoguery.

Upon his death, the torch passed to his son, Muhammad Bello, and then to his brother, Abdullahi. The intellectual dynasty endured. The Sokoto Caliphate would survive nearly a century, until British forces dismantled it at the dawn of the 20th century.

But colonial swords could not cut down the spark he had ignited.

For an idea, when it is just, does not die. It smolders. It is passed on. It is reborn.

In Sokoto’s alleyways, Qur’anic schools still preserve his teachings.

In the zawiyas of the Sahel, his poems are whispered by oil lamp light.

In the Sufi brotherhoods of Senegal, Guinea, and Niger, people still claim his wisdom, his asceticism, his light.

His manuscripts still circulate by hand.

His treatises are studied in Islamic universities across the continent.

His reflections on economics, governance, and ethics are more relevant than ever.

In this age of endemic injustice, chronic corruption, and moral loss, the Shehu returns like an echo.

He embodies the inner voice Africa has too long suppressed.

In France, his name is unknown.

It does not appear in textbooks.

No documentaries. No history classes. No statues.

And yet, Usman dan Fodio was one of the greatest state-builders of the 19th century—on any continent.

At a time when Napoleon was exporting cannons, he was exporting ideas.

This silence is no accident. It reflects an old strategy of domination: erase yesterday’s heroes to dispossess today’s people.

But in Africa, his memory does not fade.

He is a guide for young ulama,

a memory for underground resistors,

a flame for poets, mystics, and the just.

Dan Fodio did not merely defy kings.

He proposed another way.

A way where order is founded not on fear but on virtue.

Where authority is earned, not imposed.

Where faith is not a tool of power, but a moral demand.

“A state can survive impiety, but never injustice.”

— Usman dan Fodio

In a world where Africa is searching for its models, its beacons, its escape lines, the Shehu appears as an ancient star—yet never extinguished.

This is not about returning to the past.

It is about drawing inspiration from it to rethink the future.

With lucidity. With dignity. With fire.

Giving voice back to the giants in the shadows

The story of Usman dan Fodio is that of a man who, through faith, speech, and the pen, changed the destiny of an entire continent. He proved that an African could build an empire upon justice and intellect—without waiting for Europe’s approval.

To rediscover the Shehu is to do justice to an African history that is not defined solely by slave empires or colonization. It is to affirm that Africa produced its own thinkers, its own heroes, its own prophets.

Bibliography

(As listed in the original article; retained unchanged)

Asma’u, Nana. Collected Works of Nana Asma’u, Daughter of Usman dan Fodio (1793–1864). Ed. Jean Boyd & Beverly B. Mack. Michigan State University Press, 1997.

Boyd, Jean & Mack, Beverly B. One Woman’s Jihad: Nana Asma’u, Scholar and Scribe. Indiana University Press, 2000.

Gusau, Sule Ahmed. “Economic Ideas of Shehu Usman Dan Fodio.” Journal of Islamic and Middle Eastern Finance and Management, vol. 10, no. 1, 1989.

Hiskett, Mervyn. The Sword of Truth: The Life and Times of the Shehu Usuman dan Fodio. Northwestern University Press, 1994.

Hunwick, John O. “Islamic Reform in West Africa.” Sudanic Africa: A Journal of Historical Sources, no. 6, 1995.

Islahi, Abdul Azim. “Shehu Usman Dan Fodio and His Economic Ideas.” MPRA Paper No. 40916, 2008.

Last, Murray. The Sokoto Caliphate. Longman, 1967.

Lovejoy, Paul E., & J. S. Hogendorn. Slow Death for Slavery. Cambridge University Press, 1993.

Martin, B. G. Muslim Brotherhoods in Nineteenth-Century Africa. Cambridge University Press, 1976.

Ogunnaike, Oludamini. “A Treatise on Practical and Theoretical Sufism in the Sokoto Caliphate.” Journal of Sufi Studies, vol. 10, 2021.

Robinson, David. Muslim Societies in African History. Cambridge University Press, 2004.

Sulaiman, Ibraheem. The Islamic State and the Challenge of History. Mansell, 1987.

Sulaiman, Ibraheem. A Revolution in History: The Jihad of Usman dan Fodio. Islamic Publications Bureau, 1986.

Triaud, Jean-Louis. La Tijaniyya. Karthala, 2000.

Westerlund, David & Ingvar Svanberg (eds.). Islam Outside the Arab World. Palgrave Macmillan, 1999.

Table of Contents

- The Forgotten Epic of the Great Black Caliph

- The Light from Fouta

- A Poet Confronting Kings

- From Words to the Sword

- Sokoto, or the Dream of a Just State

- The Light Beneath the Ashes

- Giving Voice Back to the Giants in the Shadows

- Bibliography