On April 17, 1825, France imposed a colossal debt on Haiti in exchange for recognition of its independence. A royal decree signed under military threat, by a king nostalgic for slavery. This ransom, paid for over a century, economically shackled the world’s first Black republic. This is the erased story of a freedom with a price tag—and the burning question of long-awaited reparations.

Haïti : A nation born of fire

Haiti did not simply declare its independence. It earned it—through fire, blood, and a revolutionary war the world had never seen before.

In the final years of the 18th century, the colony of Saint-Domingue was a prosperous anomaly. It produced half of the world’s coffee and 40% of the sugar consumed in Europe. But this wealth rested on one of the most brutal slave regimes in the Atlantic world: about 500,000 enslaved Africans were kept in absolute inhumanity by a white and free minority of barely 40,000 people.

Inspired by the ideals of the French Revolution and stirred by decades of rebellion, the enslaved of the Northern Plain launched, on the night of August 22, 1791, an organized insurrection, preceded by a Vodou ceremony held at Bois Caïman. Long dismissed as superstition by official history, it remains the spiritual and strategic trigger of the revolutionary explosion.

A bloody, chaotic, multipolar war followed. France abolished slavery in 1794, but Bonaparte reinstated it in 1802. In the meantime, one man had risen to prominence: Toussaint Louverture, a former slave turned general, then governor. He ruled the island with rare political skill but was betrayed, captured, and deported to France, where he died in a freezing cell at Fort de Joux.

The torch was passed to Jean-Jacques Dessalines, his military right arm. In 1803, he crushed the French troops at the Battle of Vertières. The following year, he declared Haiti’s independence. This was not just a colonial break—it was the birth of the first modern state founded by formerly enslaved people. And above all, it was a living insult to the global racial order.

But that independence, though declared, stood alone. No Western nation recognized it. The United States, still a slaveholding nation, ignored it. France, humiliated, regarded it as a shameful loss. And already, silently, it prepared its revenge—not through gunpowder, but through contracts.

1825: When independence comes with a price

By 1825, Haiti’s independence was no longer a dream, but a fact. Still, it hung in limbo in the eyes of international diplomacy. Because to exist in international law, liberation was not enough—recognition was required.

Since 1804, Haiti had lived in the shadows. No European state wanted to legitimize a republic founded by rebellious Black people. For slaveholding monarchies, it would set a deadly precedent. Diplomats looked away, cartographers erased its borders. Silence became strategy.

But in France, a decision was brewing. Charles X, brother of Louis XVI and a reactionary king, sought to “resolve the Haitian question.” Not by restoring colonial rule—the imperial army had been broken at Vertières—but by profiting from the victor’s success.

On July 3, 1825, fourteen French warships appeared in the bay of Port-au-Prince. It wasn’t a show of strength—it was a veiled threat. Onboard was Baron de Mackau, the king’s envoy. He didn’t bring a treaty but an ultimatum: France was ready to recognize Haiti’s independence… if it paid.

On April 17, 1825, Charles X signed a royal ordinance marking one of the most cynical episodes in modern history. It stated:

“The current inhabitants of the French part of Saint-Domingue shall pay into the federal treasury […] the sum of 150 million francs, intended to compensate former colonists who demand indemnification.”

This astronomical sum—more than three times Haiti’s annual state budget—was non-negotiable. It was demanded as reparations… for the loss of slaves. The very people who had won their freedom through their own struggle.

Haitian President Jean-Pierre Boyer signed. The cannons of the French ships were aimed at the capital’s outskirts. There was no alternative. To survive as a state, Haiti had to go into debt.

And so began the double punishment. Unable to pay the initial installment, Haiti had to borrow. The first loan, contracted in Paris under predatory conditions, opened a downward spiral. Haiti paid to be free—and paid interest on that freedom.

Independence became a priced service.

The ransom of liberty was no longer just a political act—it became a transaction. The former empire no longer conquered; it invoiced. And this logic, established in 1825, would define North-South relations for the next two centuries.

The double debt: An economic and diplomatic trapque

When Haiti agreed in 1825 to pay 150 million gold francs to France, it wasn’t just purchasing diplomatic recognition. It was entering an economic system structured around the trap of debt. This debt was initially external, but soon developed into an internal, structural burden that undermined the young republic’s sovereignty.

The amount imposed by Charles X was deliberately disconnected from Haiti’s economic reality. In 1825, Haiti’s annual state revenue hovered around 10 million francs. The ordinance demanded the equivalent of fifteen years of revenue. Worse: the first payment of 30 million was due by December of that same year. Haiti was forced to borrow immediately to meet the deadline.

This first loan—known as the “Lafitte Loan,” named after banker Jacques Laffitte—totaled 30 million francs. But after commissions, issuance fees, and interest rates, Haiti only received 24 million. The remaining 6 million enriched financial intermediaries. Thus began the “double debt”: to the French state and to private creditors.

In the following years, successive Haitian governments had to adapt domestic policy to repay the debt. Tax revenues, especially from coffee exports (which made up 70–80% of national income), were almost entirely devoted to debt service.

Debt repayment became the state’s top expenditure.

To maximize tax revenue, a Rural Code was adopted. It imposed harsh rules on farmers, forcing them to reside on plantations and work under contract. This quasi-feudal system reorganized Haitian society around a single goal: maximize production to repay.

The political freedom won in 1804 was thus compromised by economic servitude. Haiti was free on paper, but structurally shackled. The debt acted like an invisible leash—more effective than any army.

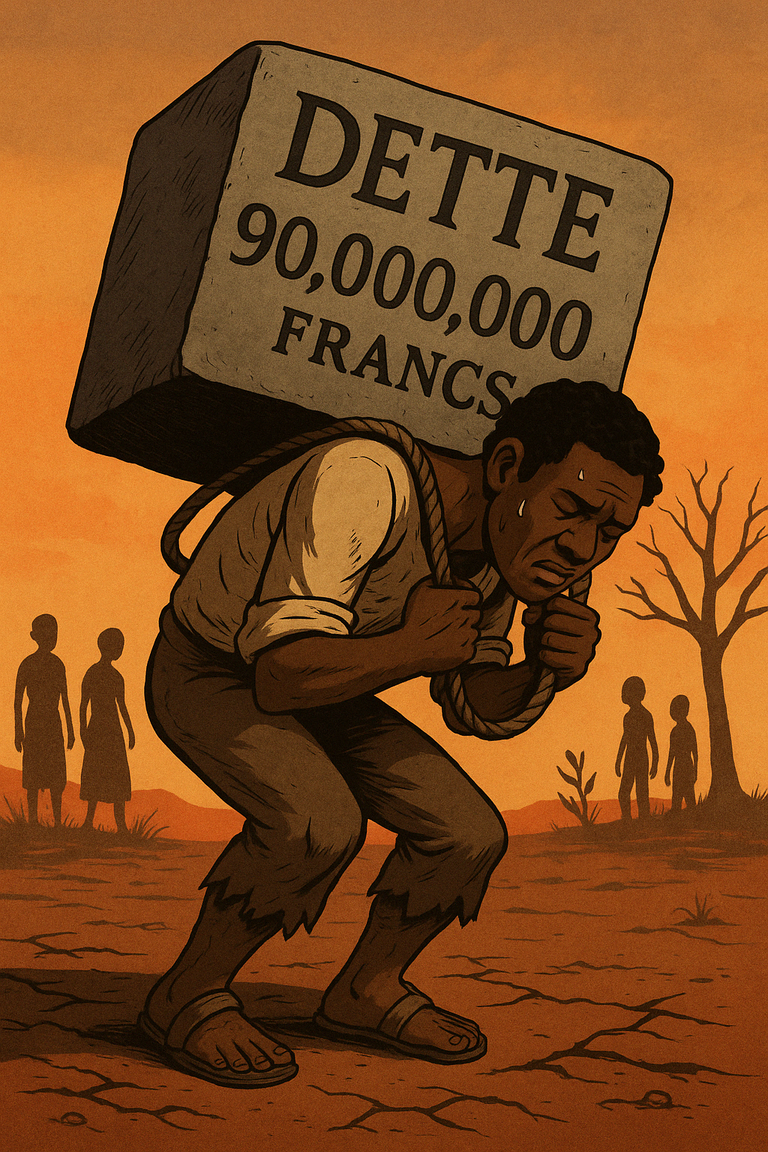

Under pressure from popular uprisings and the state’s inability to pay, a new treaty was signed in 1838. The amount was reduced to 90 million francs—still enormous, but more “presentable.” This adjustment was presented as a French concession, but it maintained the grip: Haiti remained indebted, and its independence remained conditional on timely payments.

Between 1825 and 1888, Haiti repaid the full principal. But the interest from the loans continued to accrue. The final installment wasn’t paid until 1947. That date is no accident. It was 43 years after France’s liberation by the Allied Forces that Haiti finally settled the debt of its independence.

A Black nation thus took 122 years to pay for its freedom.

From the 1840s onward, Haitian loan securities became freely traded on financial markets. Parisian, London, and New York speculators bought Haitian debt at low prices and demanded repayment at inflated values. Bourgeois fortunes were built on the back of the young Black state.

Haiti no longer controlled its monetary flows. In 1880, the National Bank of Haiti was founded… in Paris. It became the key instrument for fund transfers to creditors. From then on, the Haitian state was stripped of its economic sovereignty.

Consequences: A bled-dry people, a crippled republic

The debt of independence imposed on Haiti was not merely an economic constraint—it became a breeding ground of vulnerabilities. Far from just a financial burden, it redrew the contours of Haitian society, stifled its state, and fractured its development paths. From the Republic’s birth, it instituted an economy of survival, centered not on national interest, but on repaying a morally illegitimate debt.

Every Haitian generation from 1825 to 1947 was born under the weight of this debt. The youth—peasants, artisans, merchants—worked to export coffee, cocoa, and rum, but the revenue left the country. It did not return as schools, hospitals, or roads. It fueled Parisian vaults and absentee shareholders’ dividends.

Investments in infrastructure were rare, if not nonexistent. Roads between the countryside and ports remained in disrepair, education was underfunded, and urban planning chaotic. The state did not govern—it collected. It did not develop—it repaid.

To guarantee these repayments, the state apparatus implemented quasi-colonial control systems. The 1826 Rural Code turned agricultural workers into cogs in a fiscal machine. It banned vagrancy, required Haitians to be permanently employed on a plantation, and allowed the arrest of non-compliant individuals.

Officially abolished, slavery was reborn in new forms. The economy became a machine to produce for the outside, without redistribution. Pressured by French demands, the state enforced strict social discipline. Freedom no longer tasted like emancipation, but like forced labor.

Economic pressure on the government weakened its legitimacy. Presidents came and went, often through coups, unable to propose a true national project, as their priorities were dictated from abroad.

This chronic fragility led to peasant revolts, violent repression, and constant instability. Haiti never found a solid foundation to build lasting institutions. The military became the only structured body—not to defend the people, but to maintain the order required for economic extraction.

The country’s political life revolved around debt management, not the general will. The people were often excluded—or used as an adjustment variable.

The effects were not only economic or political—they were psychological. A nation born indebted grows up with a self-image scarred by debt. This memory of submission through money, this story of a coerced independence, seeps into collective consciousness.

Haiti’s poverty is often blamed on internal “flaws,” a “curse,” or racial or cultural clichés. But it is forgotten that, before it could build a national economy, Haiti was forced to sacrifice its foundational resources. Accusations of inefficiency often erase a history of planned impoverishment.

Notes & References

- Laurent Dubois, Avengers of the New World: The Story of the Haitian Revolution, Harvard University Press, 2004.

- C.L.R. James, The Black Jacobins: Toussaint Louverture and the San Domingo Revolution, Vintage, 1989.

- Michel-Rolph Trouillot, Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History, Beacon Press, 1995.

- Fondation pour la Mémoire de l’Esclavage, La double dette d’Haïti (1825–2025), Note No. 4, March 2025.

- Jean-Claude Bruffaerts & Marcel Dorigny, Après Vertières: Haïti, épopée d’une nation, Hémisphères, 2023.

- Jean-Bertrand Aristide, The Eyes of the Heart: Seeking a Path for the Poor in the Age of Globalization, Common Courage Press, 2000.

Contents

- Haiti: A Nation Born of Fire

- 1825: When Independence Comes with a Price

- The Double Debt: An Economic and Diplomatic Trap

- Consequences: A Bled-Dry People, A Crippled Republic

- Notes & References