Redrawing our roots

At the heart of human history, long before civilizations arose and continents bore borders, lived a woman: Mitochondrial Eve. Not the first woman in the biblical sense, but the one whose matrilineal genetic heritage connects us all, without exception. Discovered deep within the genome, she reminds us that our common cradle is African; that the dawn of humanity first broke over this motherland.

Who is Mitochondrial Eve?

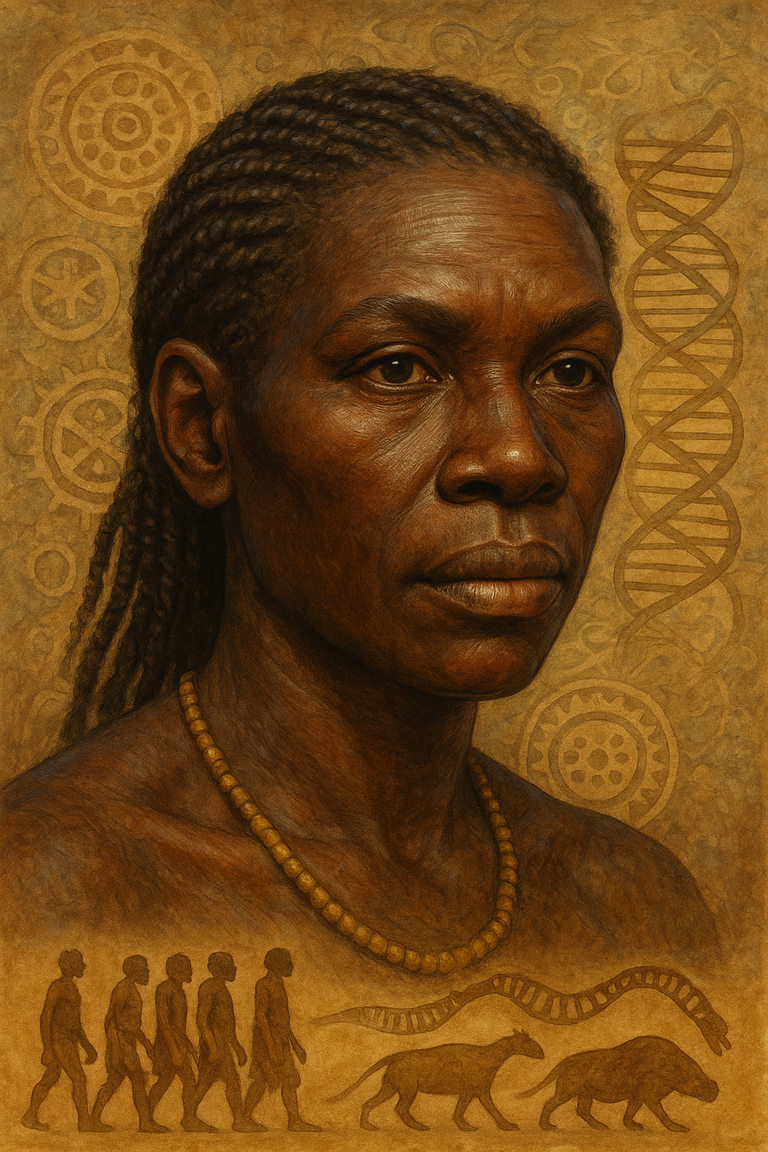

Some scientific discoveries silently shatter our oldest certainties. In the 1980s, at the crossroads of molecular genetics and anthropology, a trio of researchers (Allan Wilson, Rebecca Cann, and Mark Stoneking¹) unveiled a troubling revelation: by analyzing mitochondrial DNA²—those tiny organelles in each of our cells, passed down exclusively from mothers—it is possible to trace the thread of time back to a single female ancestor common to all present-day humans.

This woman, whom science poetically, if inadvertently, named Mitochondrial Eve³, is neither a religious figure nor a mythological being. She is a statistical reality, a point of genetic convergence. According to the latest estimates, she lived somewhere in East Africa around 150,000 to 200,000 years ago. All human maternal lineages alive today (from the Andes to the Himalayas, from the Nile Delta to the Norwegian fjords) descend from her, and her alone—through a network of mothers, daughters, grandmothers, and generations woven together across time.

But we must clarify what this ancestral motherhood does and does not mean. Mitochondrial Eve was not the first woman. Nor was she the only woman of her time. She did not live in a world devoid of other humans, nor in genealogical solitude. She was simply the only one whose female line was never broken. While other lineages—carried by real women—disappeared over centuries (due to the absence of daughters, or through random or tragic events), hers persisted, passed from mother to daughter without interruption down to us.

Here lies the fruitful paradox of this scientific figure: her universality stems from contingency. She was not the strongest, the wisest, or the most beautiful, but the most enduring. Her lineage survived. It is this survival, this invisible continuity, that grants her a symbolic stature. She is, in a way, the forgotten matrix of our shared humanity.

Of this nameless woman—whose features, language, faith, and fate are irretrievably lost—there is no tomb, no ritual memory. Yet she exists in each of us. In the breath of a young Creole girl, in the eyes of an elderly Inuit man, in the smile of a Maasai child, something of her remains: a fragment of molecular heritage, a distant note in the great biological score of humankind.

Understanding who Mitochondrial Eve is means tracing the path of our common origin. It means accepting that, despite geographic dispersions, cultural differences, and historical fractures, we belong to a single story rooted in the African depth of the world.

An african origin story

The discovery of Mitochondrial Eve is not just a scientific milestone: it is a narrative rupture. It doesn’t merely tell us where humanity begins—it shifts the center of the world. What genetics reveals is that all modern humans—from Tuareg shepherds to the banks of the Nile, from Mongolian steppes to Lima’s slums, from Asian temples to Manhattan towers—share a common origin: Africa.

This is not myth, nor a romantic origin tale. It is grounded in the rigor of molecular biology, in the meticulous analysis of mitochondrial DNA, and in cross-dated findings from paleoenvironmental and paleogenetic studies. These tools, born in the laboratories of major universities, have only confirmed what griots whispered long ago: all of humanity has an African cradle.

This is not a poetic suggestion, but a raw fact, unsettling to dominant narratives. The first human face was Black, and the first breath uttered by our species rose from the plains of East Africa. In a world yet untouched by borders, nations, or exclusions, our ancestors—with dark skin and African features—looked to the sky and began the great journey of global settlement.

This truth, long denied or marginalized in Western timelines, is now undeniable. Yet it still struggles to be fully absorbed into collective consciousness. It is more comfortable, for Europe and its descendants, to imagine history as an ascent from Greece to modernity, forgetting that Greek wisdom itself was nourished by pharaonic Egypt, trans-Saharan trade, and the knowledge of Kemet.

What Mitochondrial Eve tells us is that humanity’s memory is Black. Not symbolically Black—but literally, biologically African. And in an era when identity-based fears build walls and borders, when the Other is mistrusted for coming “from elsewhere,” this reminder is vital: “Elsewhere” is where we all began.

Every human being, regardless of skin color or birthplace, carries within a spark of Africa. It is a silent memory, nestled in our cells’ mitochondria, whispering that our differences are surface-level, our lineages entangled, and our humanity indivisible.

Restoring Africa to its place in the origin story is not a moral correction. It is a historical necessity. It is facing science and understanding that humanity’s center of gravity lies far further south than long taught.

Africa, the matrix of humanity

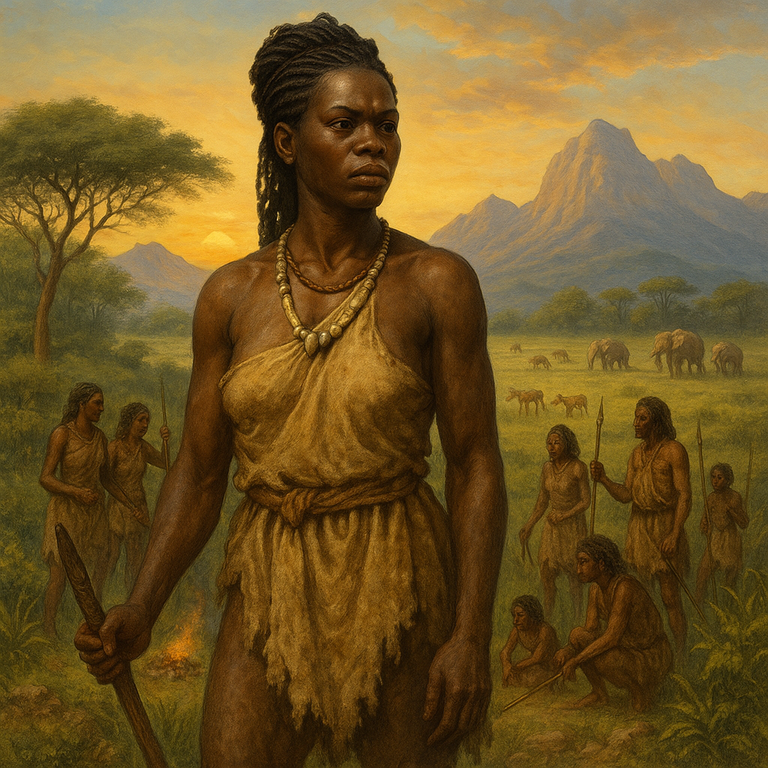

We must imagine Africa, 150,000 to 200,000 years ago, not as a land frozen in primitivism, but as a continent pulsing with biological, cultural, and social innovation. It was there—in the nourishing savannahs, the shade of equatorial forests, and the arid slopes of the Rift Valley—that humanity learned to be human.

It was in Africa that our ancestors—carrying Mitochondrial Eve’s imprint—mastered fire, crafted the first bifacial tools, began to speak, to transmit, to dream. Fire wasn’t just a survival tool: it was the first hearth, the beginning of the human circle. Shaped stones weren’t just weapons or utensils: they were the dawn of technical thought, the embryo of future civilizations.

Across ice ages and warming periods, Africa was the lab of our species, a vast theater of evolutionary learning. There, early humans adapted to climate cycles, migrating herds, and shifting vegetation. Each challenge sparked adaptation; each favorable mutation, a promise of survival.

Then, around 60,000 years ago, in a movement as discreet as it was decisive, a small group of Homo sapiens crossed Africa’s natural borders. They likely followed two main routes: the Sinai Corridor⁴, a narrow land bridge connecting Africa to the Middle East, and the Red Sea coastal route, skirting the Indian Ocean to South Asia.

These migrants weren’t conquerors, but seekers of balance: they followed rivers, tracked game, explored coasts—driven by resource needs, demographic pressure, or curiosity. They were families, clans, survivors. They carried fire, language, tools—and above all, Mitochondrial Eve’s genetic legacy.

This Out of Africa migration (known as Out of Africa II) is one of the foundational moments of our global history. From that handful of women and men—perhaps only a few hundred—descend all non-African populations alive today. Chinese, Scandinavians, Brazilians, Aborigines, Arabs, Inuit: all are, in a sense, Africans in exile.

This human dispersion did not happen overnight. It stretched over millennia, shaped by ice ages, rising seas, and unknown perils. But wherever they went, these children of Africa carried the memory of their motherland—engraved in their DNA, in their gestures, in their social structures.

And even today, despite racist ideologies, despite hierarchies built on skin color or supposed origin, science tirelessly brings us back to one fundamental truth: we are a human family born of a single matrix—Africa.

Saying this is not romanticism. It is restoring a historical, biological, and philosophical truth. It is a reminder that Africa is not the “forgotten continent,” but the founding one. It didn’t come “after”—it was the beginning.

Knowing where We come from

At first glance, Mitochondrial Eve is just a dot on a genetic map. An abstract figure buried deep in time. But looked at more closely, she is far more than a scientific artifact. She is an act of rupture. A resistance. A dismantling of the modern myth of racial division.

Her rediscovery in the 1980s—in a world still deeply scarred by racial ideologies—was a quiet but decisive earthquake. She says no to the biological borders that empires tried to impose. She says no to the idea that some are closer to “progress” than others, simply for being further from Africa.

And she says it with a formidable weapon: genetic proof. Not theory. Not slogans. But irrefutable traces, embedded in the cells of every living human. Marks left by a single maternal lineage that connects us all.

In today’s clamor of identity withdrawal—amid old chants about “blood,” “soil,” “origins”—Mitochondrial Eve asserts a powerful counter-narrative. A story of reconciliation. Of return to reality. She whispers, stubbornly, that humanity was never plural by essence, but one—in its forms, in its flaws, in its fusions.

She reminds us that racial borders are recent constructions, and that the visible differences between us are adaptive variations—shaped by climates, altitudes, UV rays. They are evolution’s garments, not signs of superiority or inferiority.

Mitochondrial Eve’s story compels us to redefine what we mean by “kinship.” For if we all carry her imprint in our cells, then the migrant we reject, the stranger we fear, the neighbor we ignore—are merely cousins, separated by a few millennia. And perhaps that is the most scandalous truth of all: she forces us to see a brother in the one we were taught to cast aside.

Summary

- Redrawing Our Roots

- Who is Mitochondrial Eve?

- An African Origin Story

- Africa, the Matrix of Humanity

- Knowing Where We Come From

Notes

- Allan Wilson, Rebecca Cann, Mark Stoneking: Molecular biology researchers who conducted pioneering work in the 1980s that led to the Mitochondrial Eve hypothesis.

- Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA): A small portion of DNA found in the mitochondria of cells (not in the nucleus), passed exclusively from mother to offspring, allowing maternal lineage to be traced over tens of thousands of years.

- Mitochondrial Eve: The name given to the most recent matrilineal common ancestor of all humans alive today, identified through mtDNA analysis. She is believed to have lived in Africa around 150,000 to 200,000 years ago.

- Sinai Corridor: A narrow land bridge linking Africa to the Middle East (modern Egypt/Israel), through which early humans are believed to have migrated to Eurasia.