Nicknamed “Amazons” by European travelers in comparison with characters from ancient Greece, the female warriors of Dahomey—known in the Fon language as Mino (“our mothers”), Ahosi (“king’s women”), Nyonu Agbo (“buffalo women”), or simply Nyonu ahwanyito (“women going to war”)—were an army of women from the Fon kingdom of Dahomey active during the 18th and 19th centuries CE. Renowned for their bravery, ferocity, and devotion to their cause, they are also known for being the only exclusively female professional army documented in modern history.

1. Historical origins

The historical development of the women’s regiment in the kingdom of Dahomey is uncertain. Their origins have sometimes been traced to a group of female elephant hunters, the Gbéto, to royal bodyguards, or to a kind of police force. Other accounts link their origins to the famous Queen Hangbe, twin sister of King Akaba (1680–1708), who is said to have established a female parallel to all the kingdom’s institutions, including the military. According to an old Mino song about a Fon campaign under King Akaba—here called Yèwunme—against the Ouéménou, allegedly led by Yahazé, their first intervention is said to have occurred then.

The first documented activities of Dahomey’s female warriors in writing date back to 1727 during the war between Dahomey and the rival kingdom of Ouidah. A foreign tradition, that of the Ashanti kingdom (modern Ghana), also mentions a women’s army in Dahomey’s forces that defeated them in 1764. However, it was not until the 19th century, under King Ghezo (1818–1858), that their use appears to have been systematized. After taking power, he freed himself from the tutelage of the Yoruba Oyo empire, to which Dahomey had been paying tribute for a century. He then attacked the Mahi populations of Hounjroto in northern Dahomey. After a heavy defeat in his first attack, he reportedly began to regularly employ a regiment of women in his future campaigns, an institution that lasted until the kingdom’s fall.

—Between 1850 and 1856

2. Becoming a Mino

Mino recruits were selected according to three criteria: criminal repression, lottery, or voluntary enlistment if the candidates had significant physical ability. While initially joining the Mino corps was seen as a punishment, the prestige gained by members over several campaigns transformed it into a kind of social advancement. They could certainly die in combat, but through their military exploits, they could achieve a heroine status that reflected honor upon their families.

Official integration into the Mino regiment occurred through a ritual common to all Gbe-speaking peoples: the “blood pact.” Also at the origin of the Bois Caiman ceremony in Haiti, this practice—revealed to men by the spirit Aziza—involved drinking a brew into which participants poured a few drops of their blood, after which they swore loyalty to one another until death under penalty of divine punishment. In the case of the Mino, new recruits gathered naked before the jexo, the tomb of the kings of Abomey, and swore before the dead and the kingdom’s protective gods to dedicate themselves entirely to the expansion and defense of Dahomey, and never to betray one another. A priest would cut their left arm, letting their blood flow into a skull filled with alcohol and powder, which they then drank. After another drink, they became members of a new community with an almost sacred status.

Integration of new Mino also included less ritualized aspects: recruits practiced wrestling, strength trials, and forest courses lasting five to nine days, where they had to survive together and adapt to the conditions of war. They endured hunger, fear, wild animals, and traps deliberately set by their leaders. Amulets and sacrifices instilled confidence in their survival abilities. During this “training,” they also learned a communication code known only to the Mino, based on imitating bird calls, which allowed them to communicate over long distances during military operations. The kingdom’s best physicians, the Kpamegan, were assigned to support them during these stages.

3. Daily life

Most Mino lived around Singbodji Square within the royal city of Abomey. A very small number were married to the king or some of his favorites. In peacetime, they engaged in palace activities, mainly related to crafts and cooking, but were fed and housed by the king. They continued systematic military training through rigorous physical and martial exercises, often accompanied by war songs and rhythms, which enabled them to master melee combat and the use of bladed weapons, though they also reportedly used firearms with less success.

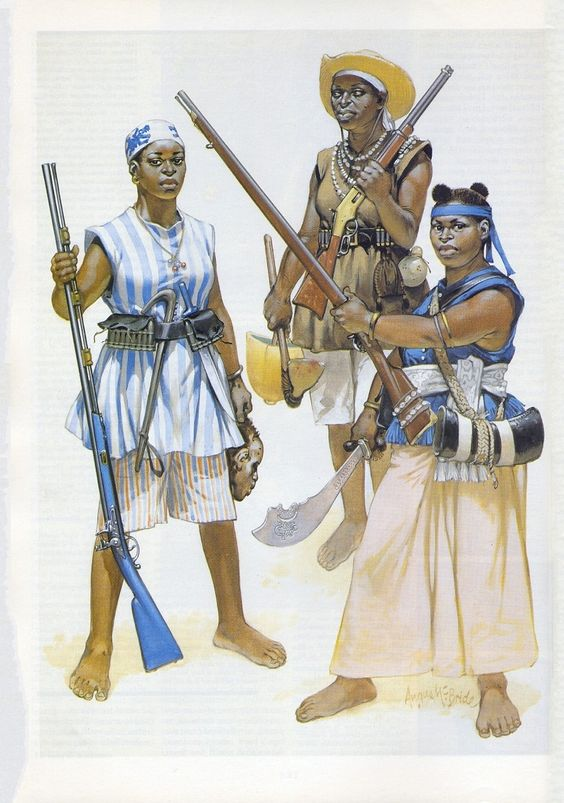

During wartime, at least annually in Dahomey, the Mino wore a uniform often consisting of a sleeveless top called Akon Awu, covering a loincloth that flattened their breasts, shorts called chokoto, and a headdress or band covering their earlobes. These garments were intended to conceal the warriors’ femininity in battle. Uniforms were sometimes accompanied by amulets, often given by the king as honors for their heroic deeds. The Mino were divided into four main units, each led by women: the Gbéto, descended from the famous female elephant hunters; the Gulonento; the Agbarya; and the Gohento, each with distinctive uniform colors.

4. Values

Key values of the Mino included devotion to the kingdom and solidarity, embodied in the Fon blood pact, the Vodunnunu (the act of “drinking the divinity”). Numerous songs and stories illustrate this spirit. For example, a Mino from the kingdom of Kétou, captured as a child by Dahomey, was freed and returned to her parents after their defeat against the city of Abéokuta. She refused to stay with them, expressing her wish to return to Dahomey to serve her king.

Another Mino value was presenting themselves as equals to men. Many songs and Fon tapestries depict them in red, the color of virility and danger par excellence.

5. In war

Beyond the 1708 battle against the Ouéménou, the Mino distinguished themselves in several battles, often outperforming their male counterparts. This includes conflicts with the Yoruba kingdoms of Savé, Abéokuta, and Kétou in 1825, 1851, 1864, and 1885, respectively. The wars against the French in 1890 and 1892, which led to Dahomey’s fall, again highlighted the courage and martial values of the Mino in foreign accounts and in Fon tradition. Today, this legacy remains widely recognized in modern Beninese culture, serving as a symbol of bravery, unity, and transcending social status for young Black people seeking to reclaim and reconstruct their historical heritage.

Bibliography