Discover how Muhammad al-Mahdi rallied followers and became an influential missionary in nineteenth-century Sudan.

The heroic journey of Muhammad al-Mahdi

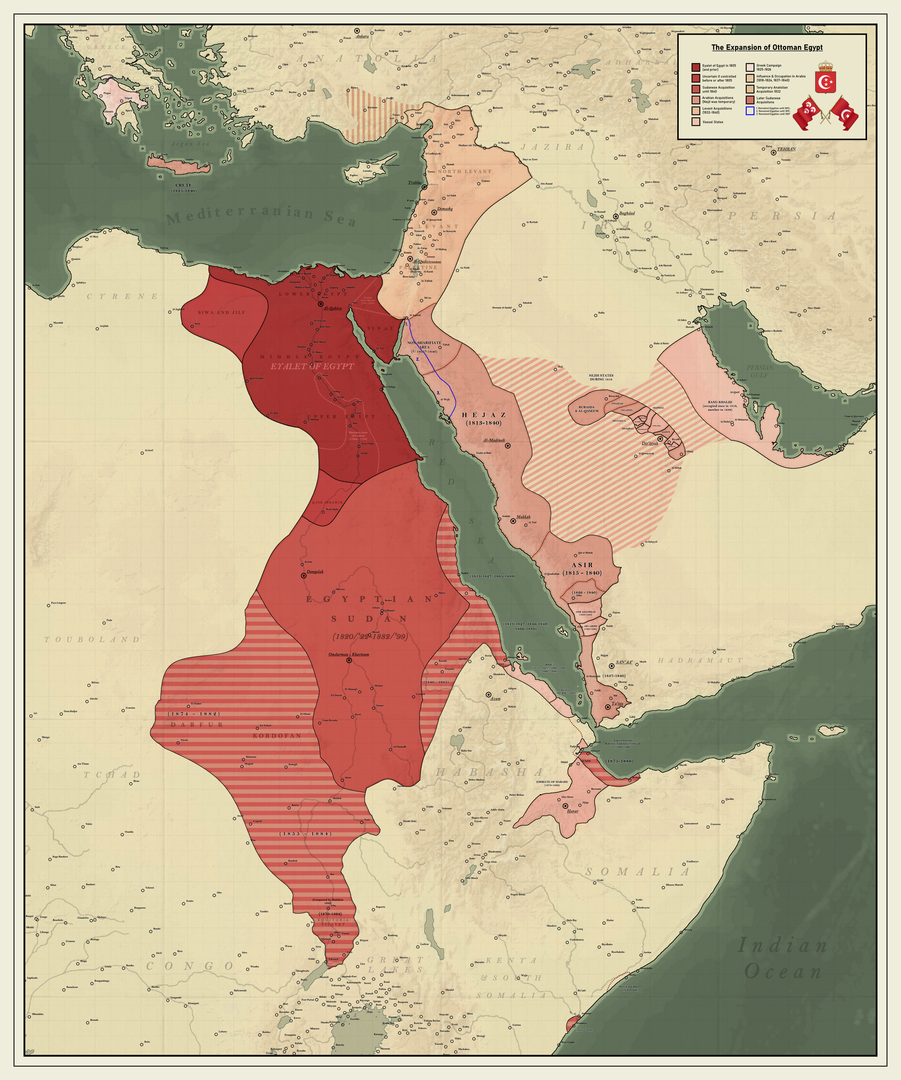

From the first half of the nineteenth century, Sudan was under the domination of a “Turkish” dynasty of Ottoman origin, which also ruled Egypt.

The physical brutality and economic oppression of this colonial rule fostered the rise of Muhammad Ahmad, a Sudanese leader who would proclaim himself the “Mahdi” — the savior of the end times in the Muslim tradition — and would succeed in defeating the Turks and the British, liberating his country and rising to its leadership.

The modest beginnings of a future leader

Muhammad Ahmad ibn Abd Allah was born in 1844 on the island of Labab, near the present-day city of Dunqulā (Dongola) in northern Sudan. His family, of modest origin, was deeply rooted in Islamic tradition. His father, Abd Allah, was a renowned boat builder who claimed descent from the Prophet Muhammad, which gave the family a certain prestige within the local community. Shortly after Muhammad’s birth, the family migrated south within Sudan, before settling north of the city of Omdurman.

From a young age, Muhammad showed a marked interest in religious life, distinguishing him from other children his age. This inclination toward spirituality was encouraged by his family, who supported his religious aspirations. However, the premature death of his father forced the family to move to Khartoum. This move marked an important turning point in Muhammad’s life, as he began attending Quranic schools in the city, immersing himself in the study of Islam and religious sciences.

His brothers, eager to maintain the family tradition, wanted Muhammad to follow in their father’s footsteps by working in boat building. Muhammad, however, was determined to devote his life to the study and teaching of Quranic sciences. A compromise was reached: he would be allowed to pursue his religious studies before joining his brothers in the family business. This period of Quranic training proved crucial, allowing him to develop a deep knowledge of religious texts and Islamic jurisprudence while strengthening his faith and spiritual devotion.

During his studies, Muhammad Ahmad was particularly influenced by the teachings of local sheikhs and by the theological debates that animated Khartoum’s religious circles. He stood out for his devotion and religious zeal, attracting the attention of his teachers and peers. His thirst for knowledge and natural charisma began to draw followers, marking the beginning of his rise as a religious leader.

Muhammad’s determination to pursue religious studies despite family pressure and economic challenges already revealed the traits of a resolute and visionary leader. This formative period forged his character and laid the groundwork for his future achievements as a religious and political leader.

The spiritual and intellectual formation of Muhammad Ahmad

Muhammad Ahmad initially considered pursuing his religious studies at the prestigious Islamic learning center of al-Azhar University in Cairo, Egypt. However, for reasons that remain partly unclear, he chose to stay closer to home and went to Berber to study under the respected Sheikh Muhammad al-Dikayr. This strategic choice allowed him to immerse himself in a more familiar environment while benefiting from the instruction of a renowned scholar.

Under the guidance of Sheikh al-Dikayr, Muhammad Ahmad distinguished himself not only through intense religious devotion but also through his social and political engagement. Very early on, he showed signs of rebellion against Turco-Egyptian rule, vehemently denouncing the economic oppression imposed on local populations. As an act of protest, he adopted symbolic gestures such as refusing to consume food provided by the Turco-Egyptian authorities. This act of defiance attracted the attention and respect of his peers and of his teacher, Muhammad al-Dikayr, who began to see in him a future leader.

Muhammad Ahmad’s influence grew rapidly, and he attracted a circle of devoted supporters. His natural charisma and his critical discourse against economic injustice resonated deeply among students and the local population. At the end of his studies, around the age of eighteen, he developed a strong interest in Sufism, a mystical branch of Islam that advocates spiritual closeness to God during earthly life. Sufism emphasizes asceticism, meditation, and the pursuit of spiritual union with the divine — concepts that fascinated Muhammad Ahmad and aligned with his desire for religious and social reform.

He joined the Sufi brotherhood led by Sheikh Muhammad Sharif Nur al Da’im, an influential order in the region. Impressed by the devotion and intellectual abilities of his new student, Sheikh Nur al Da’im granted him exceptional freedom of movement and thought. After seven years of intensive learning and religious practice under his guidance, Muhammad Ahmad reached a level of mastery that allowed him to leave his teacher’s school with his blessing.

Muhammad Ahmad was then invested with the title of Sufi sheikh, recognizing his expertise and spiritual authority. This title allowed him to transmit his own knowledge and teach new disciples, consolidating his position as a religious leader. During this period, he continued to develop his reformist ideas, advocating a return to the fundamental values of Islam and openly criticizing the corruption and injustice of the Turco-Egyptian authorities.

The years spent under the guidance of Sheikh al-Dikayr and Sheikh Nur al Da’im were crucial for Muhammad Ahmad’s intellectual and spiritual formation. They enabled him to forge his vision of a just and equitable Islamic society, thus preparing the ground for his future proclamation as the Mahdi and his role in the struggle against colonial powers.

The first steps of Muhammad Ahmad as a religious leader

Shortly after leaving the brotherhood of Sheikh Muhammad Sharif Nur al Da’im, Muhammad Ahmad undertook a series of journeys across Sudan, seeking to spread his religious teachings and gather followers. These travels were motivated by his desire to reform Sudanese society and to fight the injustices perpetrated by the Turco-Egyptian authorities. He preached a return to the fundamental values of Islam and openly criticized cultural practices he deemed contrary to religious precepts.

During one of his journeys to Khartoum, he married Fatima, one of his cousins, thereby consolidating his social status and strengthening family ties. On this occasion, he banned traditional Sudanese dances, which he judged contrary to religious morals, thus demonstrating his commitment to purifying local cultural practices. This ban reflected his desire to return to a strict and pure interpretation of Islam, rejecting cultural elements he perceived as corrupt.

Around 1878, Muhammad Ahmad began to openly criticize his former teacher, Sheikh Muhammad Sharif Nur al Da’im, notably for organizing dances during a family celebration. This public criticism was not only a personal affront but also a declaration of his commitment to rigorous religious reform. Accused of betraying Islam and seeing his student’s popularity grow dangerously, Muhammad Sharif Nur al Da’im decided to expel Muhammad Ahmad from the brotherhood. This expulsion marked a turning point in Muhammad Ahmad’s life, leaving him in search of a new spiritual home.

Despite the protests of his former teacher, Muhammad Ahmad succeeded in joining the Sufi brotherhood of the Sammaniya in Khartoum. His charisma and reputation as a fervent religious reformer quickly earned him the trust of the brotherhood’s members. In 1881, upon the death of Sheikh al-Qurashi wad al-Zayn, Muhammad Ahmad was appointed as the new leader of the Sammaniya, further strengthening his authority and influence. This strategic position allowed him to consolidate his base of followers and extend his reformist message to a wider audience.

During his travels, Muhammad Ahmad noticed a messianic expectation among the Sudanese people, who hoped for the coming of the Mahdi — a divine savior announced by Muslim tradition. Observing this expectation and strengthened by his own religious convictions, he began to envision the possibility of presenting himself as the incarnation of this messianic figure. His visions and spiritual experiences reinforced this conviction, and he began to preach this idea to his disciples, preparing the ground for his future proclamation as the Mahdi.

This period of his life was marked by intense missionary activity, during which Muhammad Ahmad did not merely preach but actively sought to transform Sudanese society. He criticized deviant practices, promoted strict observance of Islamic precepts, and mobilized his followers for a cause that went beyond the purely spiritual sphere. By presenting himself as the Mahdi, he offered a vision of hope and liberation to oppressed Sudanese people, laying the foundations of his future politico-religious movement.

This strategy of religious reform combined with a skillful exploitation of the people’s messianic expectations enabled Muhammad Ahmad to build a powerful and devoted movement, ready to challenge the Turco-Egyptian and, eventually, British colonial authorities.

From Muhammad Ahmad to Muhammad al-Mahdi, the awaited savior

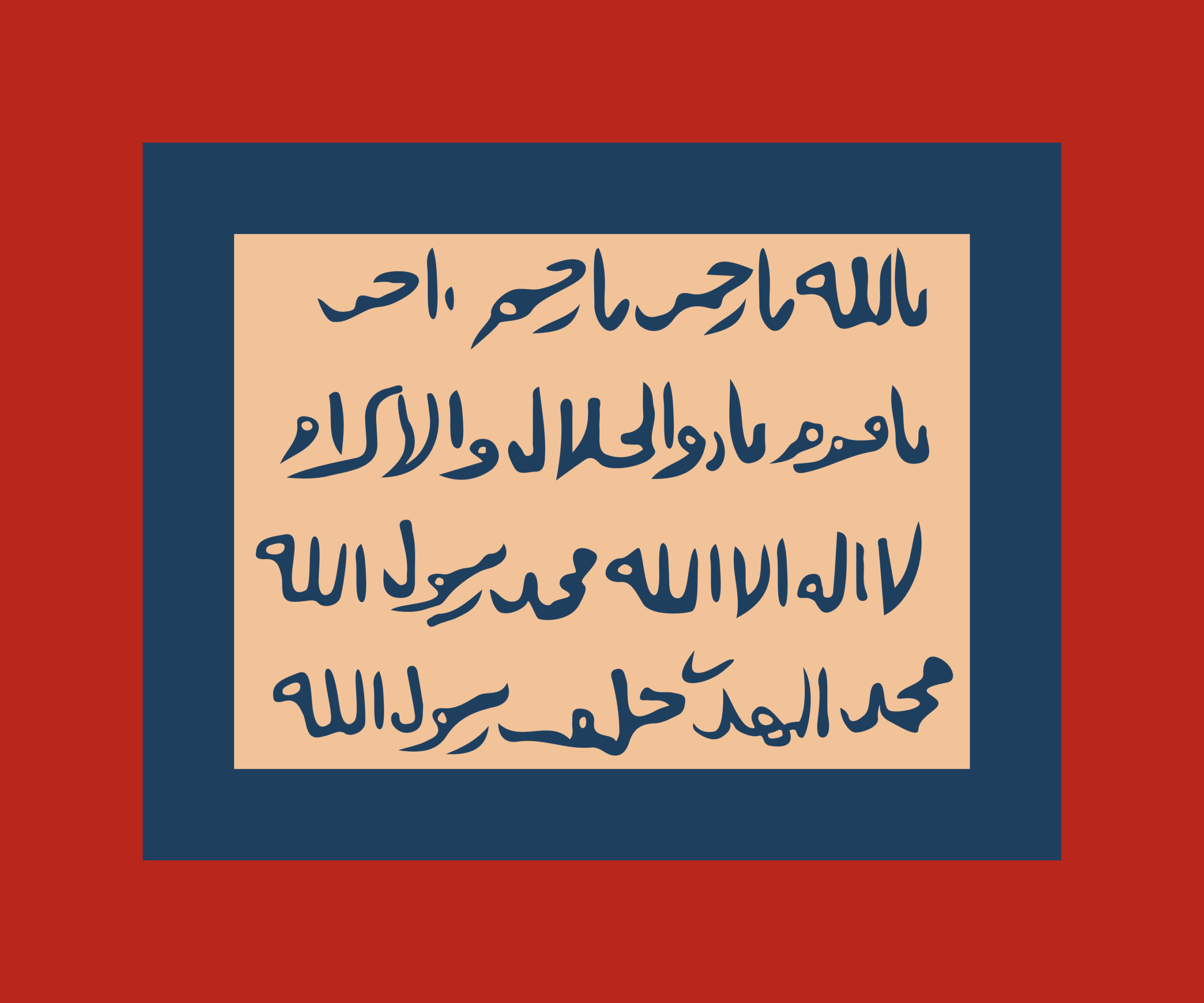

The figure of the Mahdi, though not mentioned in the Qur’an, occupies an important place in later Muslim tradition. He is seen as a messenger of God whose coming is expected to precede the end of times. The Mahdi is destined to reunify divided Muslims and to prepare the return of Jesus (ʿĪsā ibn Maryam), who will defeat al-Dajjāl (“the Deceiver” or “the Impostor”), also known as al-Masīḥ al-Dajjāl (“the False Messiah”). The expected characteristics of the Mahdi include bearing the name Muhammad, like the Prophet Muhammad, and being a descendant of him.

In 1880, Muhammad Ahmad began to be recognized by several of his disciples and supporters as the Mahdi. He reported having divine visions that revealed his mission and messianic role. These visions reinforced his conviction that he was destined to save Sudan from Turco-Egyptian oppression and to establish a just Islamic society.

In 1881, Muhammad Ahmad decided to make his mission public. He officially announced that he was the Mahdi and invited all believers to join him in fighting oppression and establishing divine justice. This proclamation attracted the attention of the Turco-Egyptian authorities, who saw him as a serious threat to their power.

The Governor-General of Sudan, Muhammad Ra’uf Pasha, ordered Muhammad Ahmad to present himself in Khartoum and submit to his authority. Muhammad Ahmad categorically refused, asserting that his divine mission transcended all earthly authority. In response, the governor sent an army to apprehend him. The confrontation that followed took place on Aba Island, where Muhammad Ahmad and his followers, though fewer in number and less well armed, managed to inflict a decisive defeat on government forces. This miraculous victory, achieved mainly with bladed weapons against an army equipped with rifles, strengthened belief in his divine mission and attracted massive support to his movement.

Following this victory, the number of his disciples increased considerably, consolidating his position as a religious and military leader. Victories against Turco-Egyptian forces were perceived by many as tangible proof of his status as the Mahdi. Muhammad Ahmad then officially adopted the name Muhammad al-Mahdi, fully symbolizing his role as a divine savior and reformer.

Muhammad al-Mahdi began structuring his movement into a true state, with representatives, an organized army, and an administration based on the Islamic principles he advocated. He established his headquarters near Mount Qadir, which he renamed Mount Massa, in accordance with traditional prophecies associated with the coming of the Mahdi.

The rise of Muhammad al-Mahdi marked the beginning of a revolutionary movement in Sudan, where his military victories and religious charisma mobilized thousands of Sudanese around his cause. The figure of the Mahdi, as embodied by Muhammad Ahmad, became a symbol of resistance against colonial oppression and of hope for a more just and pious society.

The rise to power and the challenges of Muhammad al-Mahdi

After his initial victory against Turco-Egyptian forces on Aba Island, Muhammad al-Mahdi migrated with his followers near Mount Qadir, which he renamed Mount Massa to conform to traditional predictions concerning the Mahdi. This strategic relocation strengthened the mystical and prophetic aura of his movement, attracting even more disciples convinced of his divine mission.

The Turco-Egyptian government, determined to crush this nascent rebellion, sent a new army to apprehend al-Mahdi. Upon arriving on Aba Island, however, the troops found the camp deserted. Frustrated and disoriented, they withdrew to Khartoum, but were severely affected by local diseases caused by unfavorable climatic and sanitary conditions.

Taking advantage of the disorganization of colonial forces, the Mahdi’s army launched a series of ingenious ambushes against Turco-Egyptian troops. These attacks, often carried out in difficult terrain and using guerrilla tactics, inflicted heavy losses on the invaders and undermined their morale. Muhammad al-Mahdi’s ability to mobilize his forces effectively and exploit enemy weaknesses reinforced his status as a competent and inspired military leader.

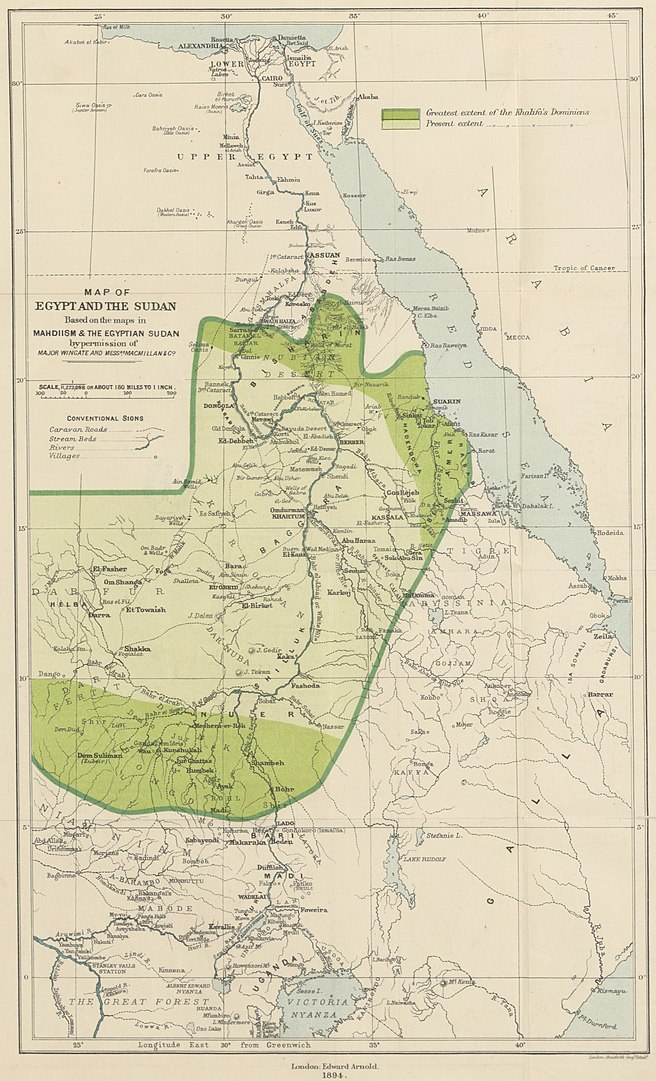

Buoyed by these successes, al-Mahdi began to establish a structured government in the territories he had conquered, al-Dawla al-Mahdiyah. He appointed local representatives to administer the regions under his control and set up a disciplined army to defend and expand his influence. This embryonic government was founded on the Islamic principles he preached, seeking to establish a just and pious society in opposition to the corrupt and oppressive Turco-Egyptian regime.

In September 1882, Mahdist forces suffered a heavy defeat at el-Obeid, where nearly 10,000 of his men perished. Despite this crushing loss, al-Mahdi was not discouraged. He decided to lay siege to the city, using blockade and harassment tactics to exhaust enemy defenses. The determination and resilience of the Mahdists eventually paid off, and after several months of siege, the city of el-Obeid surrendered to al-Mahdi. This victory allowed him to consolidate his control over the strategic province of Kordofan, further strengthening his position as an indispensable leader.

The capture of el-Obeid marked a turning point in al-Mahdi’s campaign. It not only proved his ability to overcome major military setbacks, but also demonstrated his talent for rallying and motivating his troops in times of crisis. The city’s surrender enabled him to expand his territory and assert his authority over a key region of Sudan.

The continued victories of Muhammad al-Mahdi against Turco-Egyptian forces attracted the attention of Great Britain, which began to see him as a serious threat to its interests in North and East Africa. However, before the British intervened directly, al-Mahdi continued to expand his influence and consolidate his power, laying the groundwork for future confrontations that would define his legacy.

British intervention and the struggle for Sudan

The rise of Muhammad al-Mahdi and his Mahdist forces quickly attracted the attention of Great Britain, which had recently consolidated its control over Egypt following the Anglo-Egyptian War of 1882. Concerned about growing instability in Sudan and its potential repercussions on colonial interests, the British government decided to intervene to restore order.

In 1883, Britain sent Colonel William Hicks at the head of an Egyptian army reinforced by British officers, with the mission of crushing the Mahdist rebellion. Initially, Hicks’s army achieved a few minor successes against al-Mahdi’s forces, but these victories were short-lived. On November 5, 1883, Hicks’s forces fell into an ambush near Sheikan. Al-Mahdi and his troops inflicted a crushing defeat on the invaders, annihilating nearly the entire Hicks army. This massacre greatly reinforced al-Mahdi’s popularity and political legitimacy, consolidating his image as an invincible and messianic leader.

Strengthened by this victory, al-Mahdi continued his military campaign with a series of notable successes. His forces won decisive victories in Bahr el Ghazal and Darfur, extending their control over key regions of Sudan. In 1884, Mahdist forces also gained the support of the Beja of the Eastern Desert, an influential ethnic group in the region, further strengthening their strategic and military position.

Faced with the irresistible advance of the Mahdists, the British government decided to evacuate its nationals and the remaining Egyptian officials from Sudan. General Charles Gordon, a respected military officer and administrator, was sent to Khartoum to oversee the evacuation and attempt to find a peaceful solution to the crisis. However, Gordon’s attempts at negotiation failed. Al-Mahdi, determined to pursue his divine mission, rejected all compromise proposals, including Gordon’s offer to appoint him Sultan of Kordofan in exchange for the release of European prisoners.

In January 1885, Mahdist forces launched a massive attack on Khartoum. After an intense siege, the city fell into al-Mahdi’s hands. Approximately 10,000 of the city’s 40,000 inhabitants, including Charles Gordon, were killed during the capture of the city. This victory marked Muhammad al-Mahdi’s ultimate triumph over Turco-Egyptian and British forces, consolidating his control over Sudan.

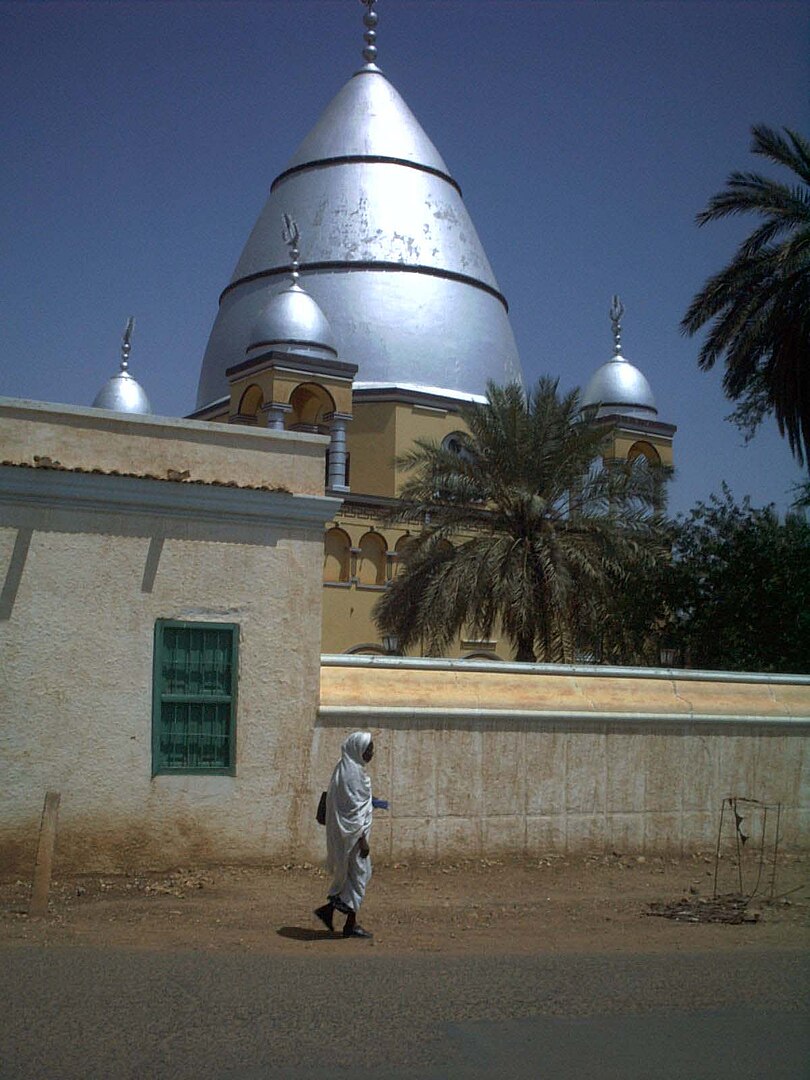

To symbolize the break with the Turco-Egyptian regime and mark the beginning of a new era, al-Mahdi decided to move his headquarters from Khartoum to Omdurman. In February 1885, he introduced a single currency for all of Sudan, thereby asserting the economic and political independence of his government. This initiative aimed to strengthen national unity and affirm the sovereignty of the new Islamic state.

Establishing his seat in Omdurman allowed al-Mahdi to centralize his power and structure his administration. Omdurman quickly became the political, religious, and military heart of the Mahdist state. Al-Mahdi implemented a system of governance based on the Islamic principles he preached, with local representatives responsible for administering conquered regions and maintaining order.

British intervention, decisive in other contexts, ended in a resounding failure in the face of al-Mahdi’s determination and military strategy. The capture of Khartoum and the death of Charles Gordon marked a turning point in Sudanese history, establishing Muhammad al-Mahdi as a leader capable of challenging and defeating European colonial powers.

However, this period of triumph was short-lived. Although al-Mahdi succeeded in unifying Sudan under his leadership and establishing a theocratic state, internal challenges and external pressures persisted. State management, internal conflicts, and the constant threat of foreign intervention continued to pose significant challenges to his regime.

The death of Muhammad al-Mahdi and the fall of his government

On June 22, 1885, Muhammad al-Mahdi died in Omdurman, most likely from illness. However, some contemporary sources suggest that he may have been poisoned by a concubine, though this version remains debated. Al-Mahdi’s death dealt a severe blow to the Mahdist movement, but his designated successor, Abdallahi ibn Muhammad, known by the title of khalīfa, quickly took control.

The khalīfa Abdallahi al-Ta’ayshi, a man of great determination and strategic mind, undertook to transform the revolutionary movement into a structured state. He divided Sudan into several provinces administered by local governors, creating a centralized and effective administration. This provincial structure helped maintain a certain level of order and manage the vast territories under Mahdist control. He also established a disciplined and well-organized army to defend the state’s borders and pursue the movement’s military objectives.

Under the khalīfa’s leadership, the Mahdist state adopted laws based on al-Mahdi’s religious precepts, instituting a rigorous theocracy. Islamic law was strictly applied, and the khalīfa sought to maintain the ideal of a pious and just society as advocated by al-Mahdi. Despite his efforts to stabilize the government and strengthen the administration, he faced numerous internal and external challenges.

Attempts to expand the Mahdist state into Egypt and Abyssinia met with significant resistance. Mahdist forces, though inspired and determined, struggled to sustain prolonged campaigns on multiple fronts. These expansion efforts drained the state’s resources and diverted attention from growing internal problems.

In 1896, Great Britain decided to reconquer Sudan to reassert control and eliminate the threat posed by the Mahdist state. Under the leadership of General Horatio Kitchener, the British launched a well-organized and methodically planned military campaign to retake Sudan. The British army, better equipped and technologically superior, advanced rapidly against Mahdist forces.

The British campaign culminated in 1898 with the decisive Battle of Omdurman, where Kitchener’s forces inflicted a crushing defeat on Mahdist troops. This battle marked the effective end of organized Mahdist resistance and paved the way for the complete reconquest of Sudan by the British in 1899. The khalīfa Abdallahi was captured and killed, bringing the Mahdist government to an end.

The fall of the Mahdist government in 1899 ended a period of relative independence and radical religious reform in Sudan. Although the Mahdist state failed to withstand imperial forces, the legacy of Muhammad al-Mahdi endures. He is remembered as a charismatic leader who, through unshakable faith and a clear vision, challenged and defeated European colonial powers during a critical period in Sudanese history.

The influence of Muhammad al-Mahdi and his movement is still felt in the history and culture of modern Sudan. His call for social justice and religious reform continues to inspire current generations, and his struggle against colonial oppression remains a symbol of resistance and determination in the pursuit of a better future for Sudan.