Beyond the assassination of Malcolm X lies a state strategy: surveillance, infiltration, sabotage. A look back at COINTELPRO, the FBI’s secret program designed to neutralize Black dissent. An invisible war, still unfinished.

The COINTELPRO program

Behind this bureaucratic acronym (COINTELPRO, short for Counter Intelligence Program) lies one of the darkest chapters of 20th-century American political history.

Launched in 1956 by the Director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), J. Edgar Hoover, the program was officially intended to “protect national security against internal threats.” In practice, it was aimed at neutralizing any movement or individual perceived as radical, dissident, or subversive—outside the dominant, moderate white political spectrum.

Its initial targets were Communist activists, but the apparatus quickly turned toward civil rights struggles and, above all, Black movements seeking dignity, justice, and autonomy. Among the organizations actively monitored, infiltrated, or sabotaged:

- Nation of Islam (NOI)

- Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC)

- Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC)

- Black Panther Party

- Revolutionary Action Movement (RAM)

But the program didn’t stop with Black American movements: radical labor unions, anti-colonialists, Chicano activists, second-wave feminists, and opponents of the Vietnam War were also targeted.

In a classified memo dated March 4, 1968—less than a month before Martin Luther King’s assassination—the FBI chillingly stated its objective:

“Prevent the rise of a ‘Black Messiah’ who could unify and electrify the Black nationalist movement.”

This phrase (“Black Messiah”) appears repeatedly in internal documents. It refers to a figure capable of giving ideological, emotional, and strategic cohesion to Black rebellion. The FBI feared not so much isolated revolts as their convergence under a common banner. It is in this light that Malcolm X was identified early on as a major threat.

He was not just a charismatic speaker:

- He offered a systemic analysis of racism;

- He advocated for community autonomy;

- He built bridges between national and international struggles, from Harlem to Accra to Algiers.

In Hoover’s eyes, this was enough to mark him for “neutralization”—a vague term that encompassed surveillance, intimidation, sabotage, isolation, and sometimes, complicity in assassinations.

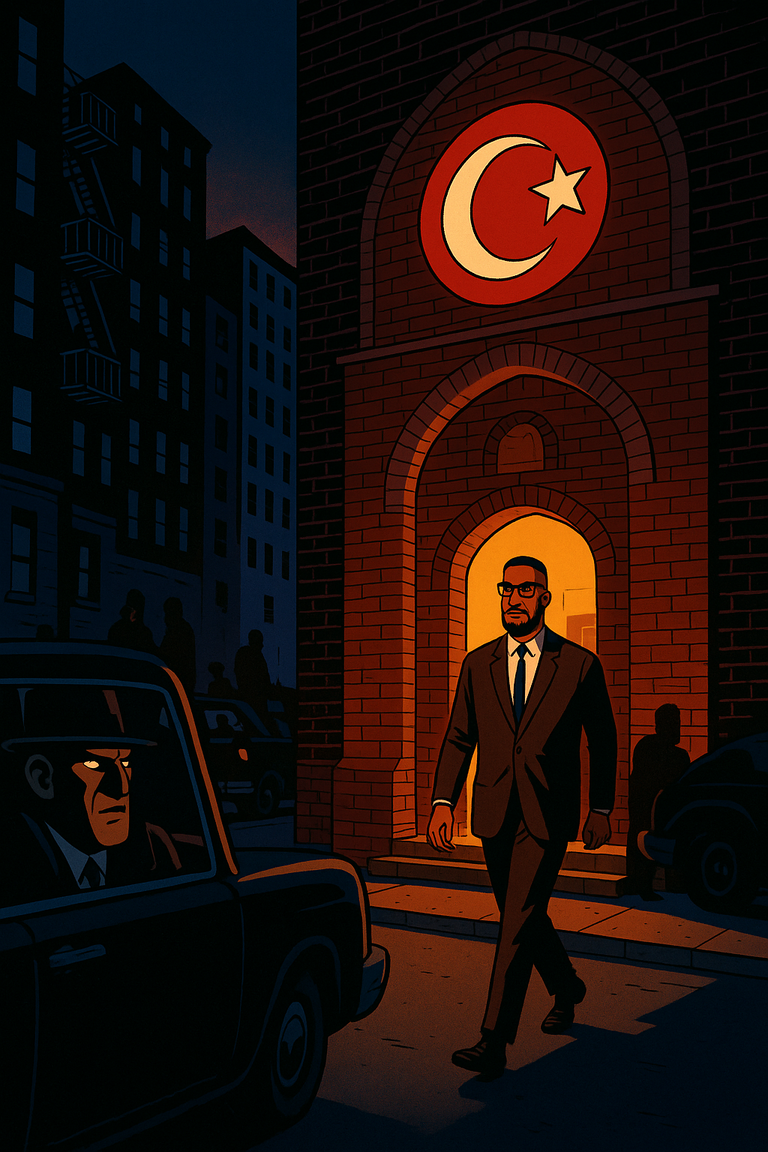

Malcolm X under constant surveillance

Very early on, Malcolm X became a top priority target for the FBI. As soon as he rose to prominence within the Nation of Islam in the 1950s, his speeches, his commanding presence, and his radical rhetoric caught the attention of intelligence services.

For the Bureau led by Hoover, the equation was simple: the more a Black leader gains popularity and symbolic power, the more they must be neutralized.

The FBI deployed its full surveillance arsenal against Malcolm X:

- Systematic wiretapping of his personal and organizational phone lines;

- Recruitment of internal informants within NOI-affiliated mosques—some embedded directly in his inner circle;

- Daily activity reports covering his speeches, travels, contacts with African and Arab diplomats, and emerging political alliances;

- Indirect media control to shape his public image, particularly through smear campaigns.

These practices—long denied—were exposed through the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) and confirmed by thousands of declassified pages in the 1990s and 2000s.

When Malcolm left the Nation of Islam in 1964 to found Muslim Mosque Inc. and later the Organization of Afro-American Unity (OAAU), surveillance intensified dramatically. Why? Because he ceased to be a religious preacher and became a transnational political actor.

- He undertook a pilgrimage to Mecca and underwent an ideological transformation,

- Met with African heads of state, took a stand on decolonization,

- Considered bringing the plight of Black Americans to the UN, framing police violence as a violation of international human rights.

To the FBI, this shift was a major geopolitical threat. He was no longer a local agitator, but a defiant diplomat capable of linking the Black American condition to the broader anti-colonial movement.

The most troubling FOIA-revealed documents show that:

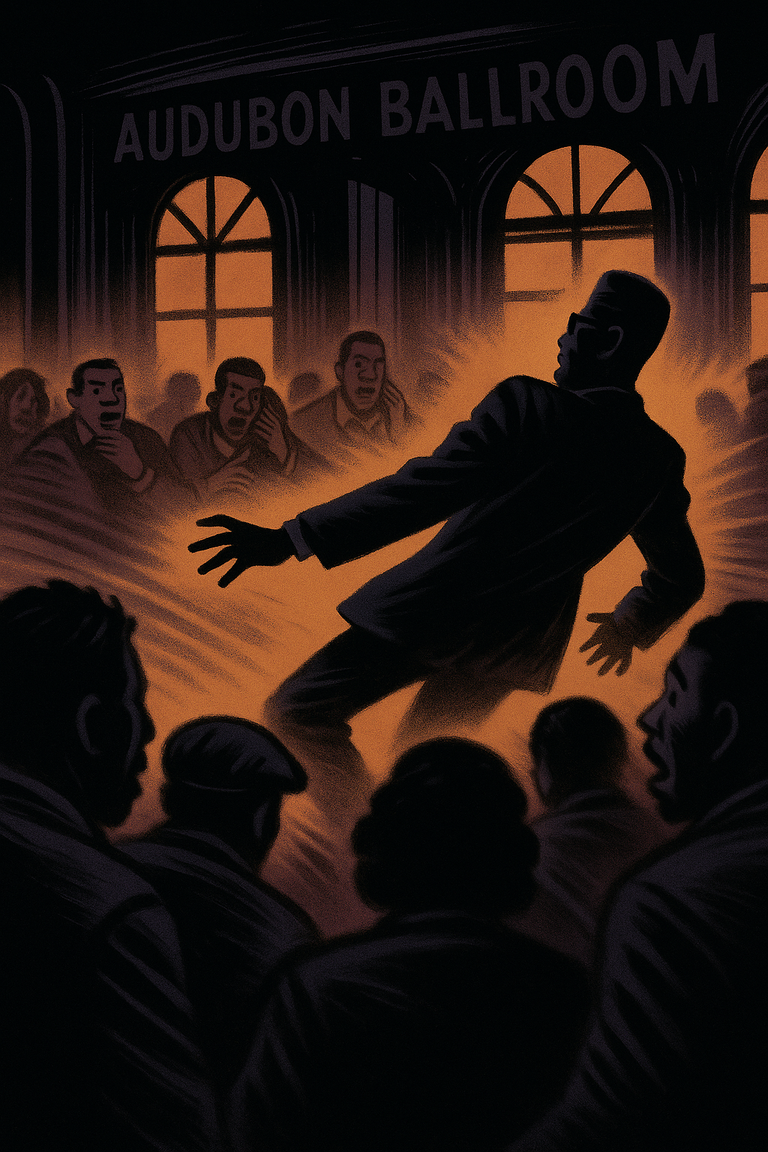

- Several FBI informants regularly attended Malcolm X’s meetings—some were present at his assassination on February 21, 1965, at Harlem’s Audubon Ballroom;

- William Bradley, the main suspect in the shooting, had links to law enforcement, fueling decades of suspicion;

- One undercover agent was reportedly the first to administer CPR—before any official medical help arrived. That gesture still raises doubts today about the authorities’ knowledge of (or passive complicity in) the attack.

In 2021, the Manhattan Conviction Integrity Unit officially acknowledged that authorities had withheld crucial evidence during the trial, leading to the exoneration of two wrongfully convicted men.

The question is no longer whether Malcolm X was under surveillance—but how far that surveillance extended, and where it ends in the chain of responsibility surrounding his death.

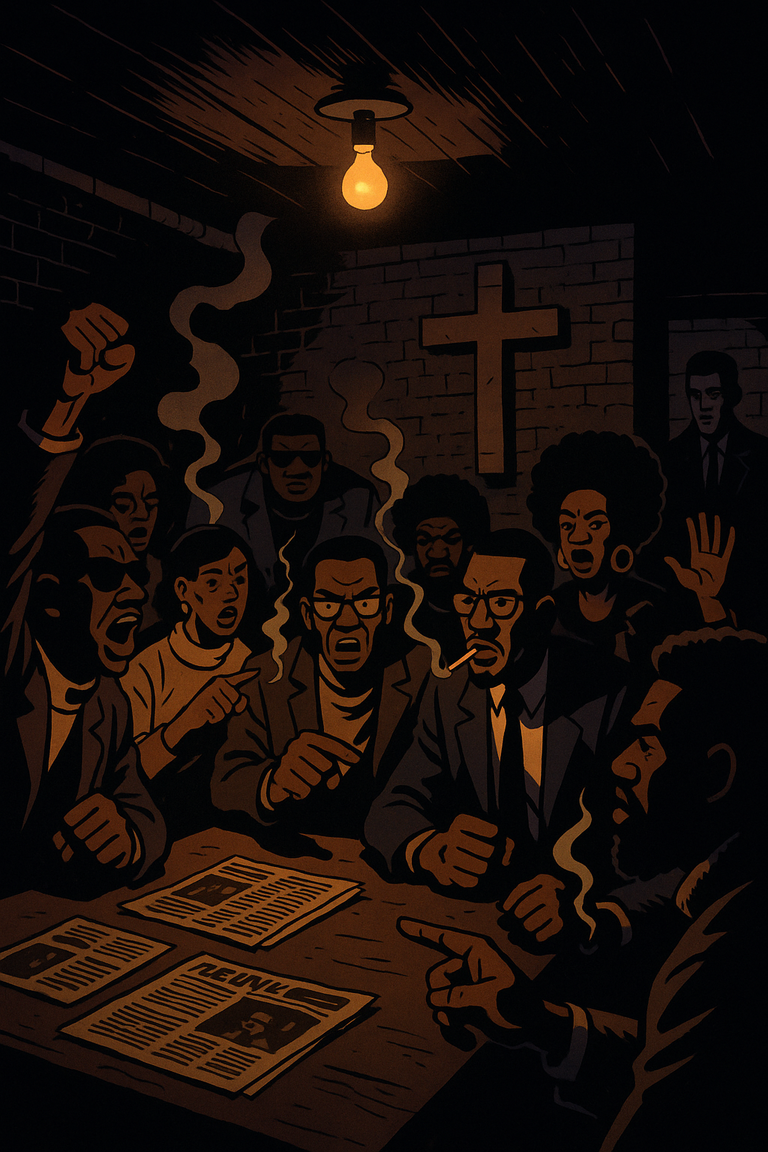

The strategy: Divide to neutralize

COINTELPRO was not merely about spying. Its goal was more insidious: to dismantle from within what power could not destroy from without.

The program relied on a strategy honed by military and intelligence forces: implode the enemy through its own contradictions. But here, the “enemy” was not a foreign army—it was Black dissent.

The techniques were as sneaky as they were effective:

- Rumors fueled by anonymous letters supposedly from rival activists,

- Doctored recordings to breed suspicion among allies,

- False accusations of betrayal, embezzlement, or collusion with authorities,

- Exploitation of egos, ambitions, and ideological divides.

One explicit objective, cited in internal FBI memos from 1968, was to “capitalize on existing conflicts among militant Black groups”—especially between the Black Panthers, the Nation of Islam, SNCC, and Pan-Africanist factions.

When Malcolm X left the Nation of Islam in 1964, the break was political, ideological, spiritual—and personal. He accused Elijah Muhammad of violating Islamic moral codes, notably through relationships with young secretaries. The Nation, in turn, considered him a renegade.

But this real tension was worsened and manipulated by federal agencies.

Declassified FBI documents show that agents stoked hostility by circulating threats, cartoons, and false alerts between both camps:

- Letters allegedly from NOI members labeled Malcolm a traitor,

- Messages were relayed to Malcolm’s inner circle, claiming he was the target of an internal plot,

- Infiltrated agents in both circles reported, amplified—and at times provoked—incidents.

The aim: create an atmosphere of fear, paranoia, and irreversible fracture.

On the day of his assassination, February 21, 1965, security around Malcolm X was shockingly minimal:

- No proper security checks at the entrance,

- No federal agents posted, despite known threats,

- A single armed bodyguard—neutralized at the onset of the attack.

The Nation of Islam was declared solely responsible through the conviction of three of its members. But:

- Two were exonerated in 2021 after 55 years of wrongful imprisonment,

- And the man believed to have fired the fatal shot was never pursued by the justice system.

This judicial murkiness and the state’s voluntary inaction reinforce a now serious historical hypothesis:

The FBI, while not pulling the trigger, may have allowed it to happen—or helped create the conditions for it.

The divide-and-conquer strategy didn’t just weaken Malcolm X. It became a blueprint for dismantling numerous Black movements thereafter—breaking coalitions, isolating leaders, and turning liberation struggles into internal disputes.

COINTELPRO didn’t only aim to silence voices. It aimed to pit them against each other—until erasure.

A Blurred memory, a duty to investigate

For more than half a century, the official version of Malcolm X’s assassination was based on a judicial truth now proven false. Three men were convicted: Talmadge Hayer (aka Thomas Hagan), Muhammad Aziz, and Khalil Islam—two of whom always claimed their innocence.

In November 2021, a major turning point reshaped this long-frozen story:

Manhattan District Attorney Cyrus Vance Jr. announced the exoneration of Muhammad Aziz and Khalil Islam, after a joint investigation with defense attorneys and the Innocence Project.

The findings were damning: the FBI and NYPD had knowingly concealed key documents that could have exonerated the men as early as their 1966 trial.

Revealed archives show that federal agencies had information proving the men’s innocence but chose not to share it with defense attorneys or the court.

- Withheld witness testimonies,

- Suppressed alternate leads,

- Undisclosed infiltrations.

Khalil Islam died in 2009 without ever being cleared. Muhammad Aziz, released in 1985, spent 20 years in prison for a crime he didn’t commit.

The State of New York awarded them $36 million in compensation—but no money can restore a damaged truth or a scarred collective memory.

Though this exoneration is a step forward, it raises more questions than it answers. Because the revelations don’t stop there:

- The FBI had agents embedded within the OAAU,

- The NYPD had informants in the very room where Malcolm was assassinated,

- Crucial evidence about the true shooters’ identities remains unreleased.

To this day, dozens of documents related to Malcolm X’s case remain classified, particularly those concerning:

- Internal FBI decisions prior to the assassination,

- Connections between the Nation of Islam and intelligence agencies,

- The exact breakdown of security around Malcolm X.

In the face of this persistent opacity, historians, families, legal experts, and Black movements continue to demand what the state still refuses:

- Full declassification of all archives,

- An independent commission of inquiry,

- Official recognition of institutional responsibility in Malcolm X’s assassination.

This isn’t merely about individual justice.

It’s a battle for historical truth, for the memory of a man whose erasure was never neutral.

To erase Malcolm X was not to erase a man.

It was to prevent the rise of a conscious, organized, sovereign people.

Sources:

- FBI Vault – Malcolm X File

- National Archives – COINTELPRO Records

- Malcolm X: A Life of Reinvention, Manning Marable (2011)

- The FBI and Martin Luther King Jr., David J. Garrow (1981)

- Documentary: MLK/FBI (2020), by Sam Pollard

- Columbia University – The Malcolm X Project

Contents

- The COINTELPRO Program

- Malcolm X Under Constant Surveillance

- The Strategy: Divide to Neutralize

- A Blurred Memory, a Duty to Investigate

- Sources