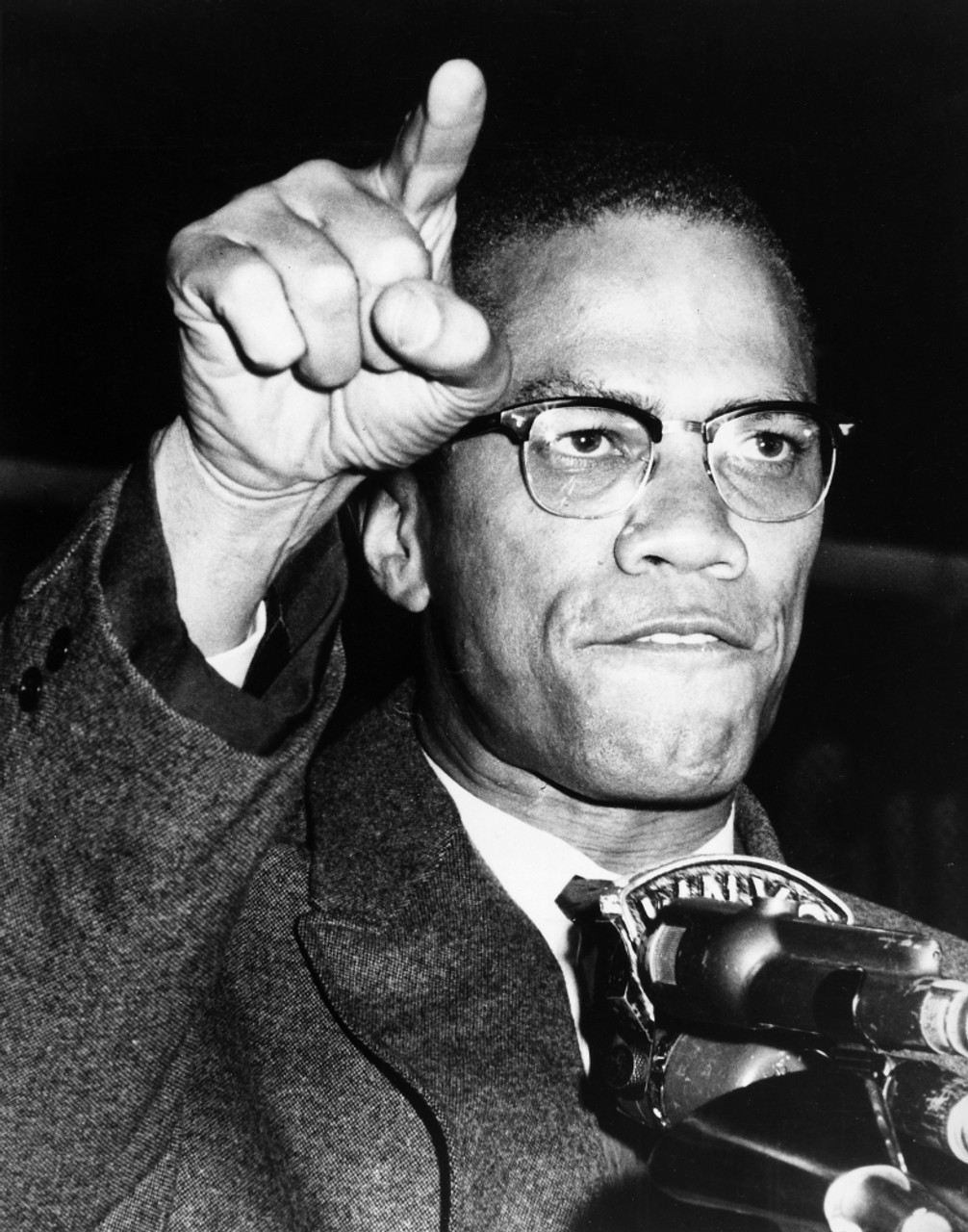

A century after his birth, Malcolm X continues to disturb. Radical thought, Pan-African strategy, rejection of compromise—he embodies a defiant voice that history has never managed to digest. Portrait of a man who became a compass, not a relic.

The man who didn’t ask for peace

A hundred years after his birth, Malcolm X remains a figure people look at sideways.

Neither canonized nor consensual, he resists easy commemorations. He never allowed himself to be simplified into a narrative of reconciled history. He was not there to reassure; he was there to disturb.

While other civil rights figures have been gradually smoothed out, appropriated, stripped of their original radicalism, Malcolm X still escapes national and global digestion. He remains a raw shard in the eye of power, a voice that does not negotiate. He never asked for integration, but for reparation. Never abstract equality, but real, inalienable Black sovereignty.

His thought is disturbing because it begins with a simple premise—unacceptable to many:

“You can’t have capitalism without racism.”

With this sentence, he points to what others evade: the structural link between economic exploitation, racial domination, and globalized imperialism.

For him, this is not a moral flaw to be corrected, but a system to be dismantled.

And what this clarity still produces today is not respectful nostalgia toward a historical figure, but discomfort. The discomfort of a man who never asked for peace, because justice had never been delivered.

A radicality forged on the margins

He was not born radical. He became so.

Malcolm Little, born in 1925 in Omaha, Nebraska, did not grow up in a neutral world. His father, Reverend Earl Little, a Garveyite activist, was found dead under a streetcar—what the family always considered a disguised lynching. His mother, broken by the welfare system, was institutionalized. The child was placed, displaced, made invisible. Very early on, Malcolm understood that the structures meant to protect were often the first to destroy.

A brilliant yet quickly sidelined teenager, he dropped out of school after a teacher told him becoming a lawyer was “not a realistic goal for a Black boy.” He drifted into street life, became “Detroit Red,” and disappeared into the margins—where Black people recycle themselves into invisibility.

In prison at age 20, he underwent an intellectual metamorphosis. He read voraciously, copied the dictionary by hand. He joined the Nation of Islam, a Black politico-religious movement preaching racial separation, discipline, and economic autonomy. This was not reintegration—it was rearmament.

In the segregated America of the 1950s, he became the voice that refused to beg.

Where Martin Luther King turned the other cheek, Malcolm held up a mirror.

He did not believe in loving one’s neighbor when that neighbor wielded a baton.

He preached self-defense, freedom without permission, Black pride without concession.

“I’m for truth, no matter who tells it. I’m for justice, no matter who it’s for or against.”

His radicalism is often caricatured. But in truth, it stems from rigorous political analysis:

- Racism is not residue—it is infrastructure.

- America is not hypocritical—it is consistent with its foundations.

- The social order is based on organized racial exclusion, not moral failure.

Malcolm X was not merely a product of the violence of his time; he was a revealer of its logic.

A thought in constant evolution

What makes Malcolm X great is not only his radicalism. It’s his ability to evolve without renouncing himself, to transform without betrayal.

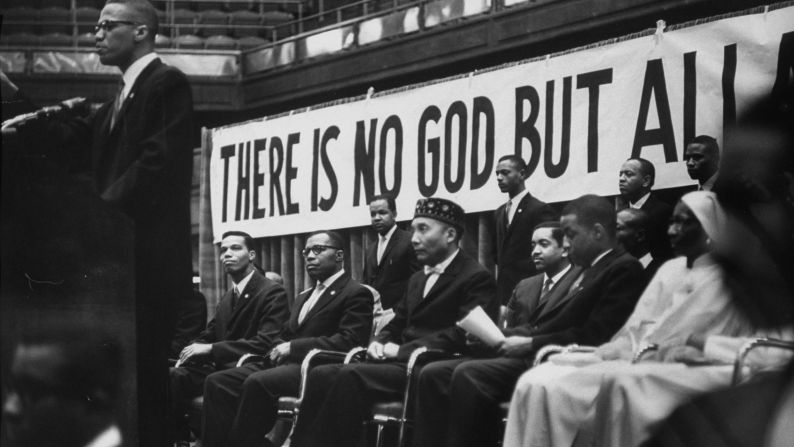

During his time within the Nation of Islam, he embodied a rhetoric of strict separation between Black and white, fueled by a visceral rejection of the West and a disciplined spirituality. But in 1964, he broke away. He left the Nation—disillusioned with the hypocrisy of its leaders and in search of a broader horizon.

This marked a decisive turning point in his intellectual and political path.

He undertook the pilgrimage to Mecca, and there, in the heart of the Ummah, he encountered a transracial, non-hierarchical spiritual community, where whites, Blacks, and Arabs prayed together. What he had once seen as fixed—race as destiny—began to shift.

He wrote:

“I have seen white people who were not racist. It changed me.”

But this change was not a renunciation. It was a strategic opening, not a naïve conversion.

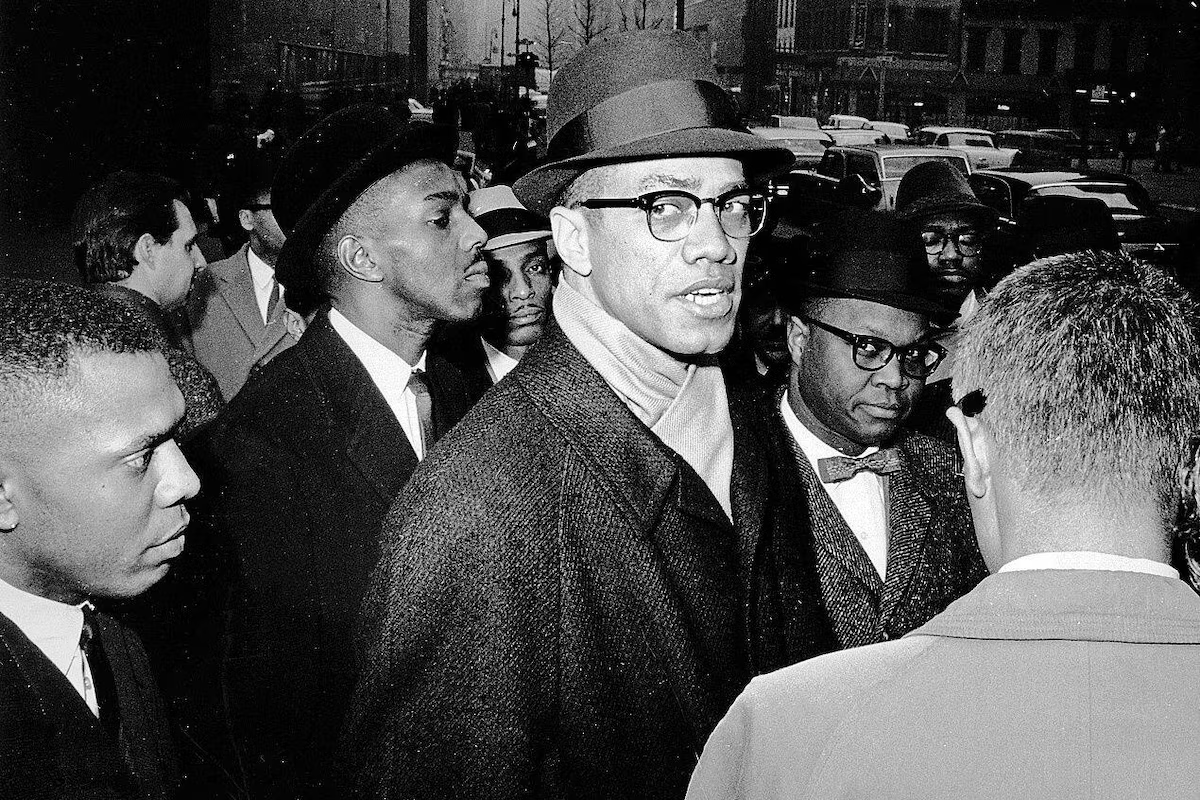

Upon returning, he traveled through revolutionary Africa: Nkrumah’s Ghana, Nyerere’s Tanzania, FLN’s Algeria. He came to understand that the African American cause was inseparable from anti-colonial liberation struggles.

- Black Americans were an internal colony.

- Racism was not a moral problem but a cog in global imperialism.

He then founded the Organization of Afro-American Unity (OAAU), modeled on the Pan-African Organization of African Unity (OAU), to build a front of the oppressed, beyond borders and dogmas. He met with OAU leaders, spoke at the UN, made contact with Marxist, Muslim, and non-aligned leaders.

He was no longer merely the voice of Harlem’s ghettos—he became the political ambassador of an awakening global diaspora.

And what makes his evolution so rare is that it never diluted his radicalism.

It sharpened it.

He never renounced his critique of capitalism nor his demand for Black sovereignty. But he wove them into a geopolitics of liberation—where Palestine, Vietnam, and the Congo became mirrors of Black America.

A century later, few figures have managed, like him, to articulate so clearly the link between race, class, and empire. Few have dared to say that racism cannot be fought without also attacking the economy that makes it profitable, and the geopolitical domination that justifies it.

It is this intellectual act—broad, unyielding, transnational—that makes Malcolm X not only a radical thinker but a strategist of global liberation.

A living and fragmented legacy

Malcolm X’s assassination on February 21, 1965, at the Audubon Ballroom in Harlem, did not end his influence. On the contrary, it multiplied his identities.

Since that day, Malcolm X has reappeared in multiple, sometimes contradictory forms:

- in urban struggle slogans,

- in the raps of Public Enemy or Tupac,

- in murals, textbooks, closing quotes of speeches,

- in prison cells, classrooms, and declassified archives.

But while Malcolm X haunts America, he does not reconcile it.

He has not become a consensual icon. Unlike Martin Luther King, transformed into a tutelary figure of nonviolence and folded into the national narrative, Malcolm X resists appropriation.

Why? Because he refuses neutrality.

He embodies a fractured memory, without happy ending, a rage that does not apologize, a refusal to bend to the terms of the powerful. He forces us to confront not the moral error of racism, but its structural function: to produce hierarchy, justify plunder, sustain fear. And he forces us to ask a brutal question the official story avoids:

What if the violence of the oppressed was not a failure, but a logic of survival?

His legacy is thus alive—but fragmented:

- Some cite him for his eloquence,

- others for his Pan-African vision,

- others still for his uncompromising Black identity.

But few embrace the whole, the radical coherence of his thought. Few accept to see him as a complete political intellectual: strategist, teacher, and theorist of global power dynamics.

He does not allow forgetfulness. He denies comfort. He reactivates, again and again, a Black voice that does not beg, does not plead—but demands.

And that is perhaps, more than anything, what still makes him intolerable to those in power:

Malcolm X didn’t want to be loved.

He wanted Black people to be free—fully, radically, unconditionally.

Why he still disturbs

What still makes Malcolm X so disturbing today is not his anger—but what it reveals.

He did not merely denounce visible injustices.

He exposed the invisible foundations of a social order that claims to be democratic while systematically producing racial inequality.

He bluntly named what many prefer to silence:

- Police brutality, not as excess, but as mechanism;

- Institutional hypocrisy, which celebrates diversity but rejects redistribution;

- The violence of erasure, which deletes centuries of Black resistance from schoolbooks.

He disturbed because he refused strategic silence—the kind that waits for “the right moment,” that asks politely, that avoids offending white sensibilities.

“We are not here to integrate into a burning house.”

He believed in the necessity of a discourse without compromise—where Black dignity is not negotiated, where freedom is not requested, but seized, where reconciliation does not precede reparation.

It is precisely this refusal to soften that makes him, even today, impossible to absorb into a world saturated with digestible narratives:

- decorative anti-racism, without political leverage,

- historical memory stripped of its conflicts,

- consumable Black culture—remixed, exported, but emptied of subversive charge.

Malcolm X cannot be sold.

He does not reassure—he provokes.

He does not seek applause—but awakening.

He does not soothe—he politicizes.

That is why he disturbs: because he forces a choice.

Not between him and King—but between resistance and consent.

And that choice, he posed it without compromise, without soft transition, without lukewarm words.

Sources

- Malcolm X & Alex Haley, The Autobiography of Malcolm X

- Manning Marable, Malcolm X: A Life of Reinvention, Penguin, 2011 (Pulitzer Prize)

- Stanford University – King Institute, Malcolm X overview

- U.S. National Archives – Malcolm X FBI files (declassified)

- PBS – Malcolm X: Make It Plain (1994)

- The Malcolm X Project – Columbia University (extensive database)

Summary

- The man who didn’t ask for peace

- A radicality forged on the margins

- A thought in constant evolution

- A living and fragmented legacy

- Why he still disturbs

- Sources