The transatlantic slave trade represents one of the darkest periods in human history. Over approximately four centuries, millions of Africans were deported, sold, and forced into slavery, with repercussions still felt in societies worldwide. Nofi traces the key milestones of this inhumane economic enterprise, from its inception to its gradual abolition, through its peak.

I. The early stages of the trade (15th – 16th Centuries)

The initial contact between European merchants and African regions, particularly along the West Coast, marked the beginning of a brutal trade system that would persist for centuries. This period is defined by events that laid the foundation for the transatlantic slave trade. Economic motivations, technological innovations, ideological justifications, and complex alliances between Europeans and Africans contributed to the establishment of a large-scale human exploitation system.

1415: The capture of Ceuta

On August 21, 1415, under the reign of King John I of Portugal, Portuguese forces captured Ceuta, a strategically located port city in northern Morocco. This marked the beginning of Portugal’s colonial ambitions in North Africa and served as a turning point in European overseas expansion. Ceuta, renowned for its wealth and its role as a hub in trans-Saharan trade, became a significant asset for the Portuguese crown.

The primary motivation for capturing Ceuta was economic: the Portuguese sought to control the lucrative trade routes of gold, spices, and other exotic goods that flowed from Africa into Europe. However, the conquest also had political and religious implications, as it was framed as part of the Christian Reconquista, a broader campaign against Islamic powers in the Iberian Peninsula and North Africa.

Ceuta served as a base for future Portuguese explorations along the African coast. Prince Henry the Navigator, the son of King John I, played a crucial role in promoting these expeditions, seeking not only wealth but also opportunities to spread Christianity. The capture of Ceuta signaled the start of a new era of maritime exploration and laid the groundwork for Portugal’s eventual dominance in the Atlantic slave trade.

1441: First portuguese captures

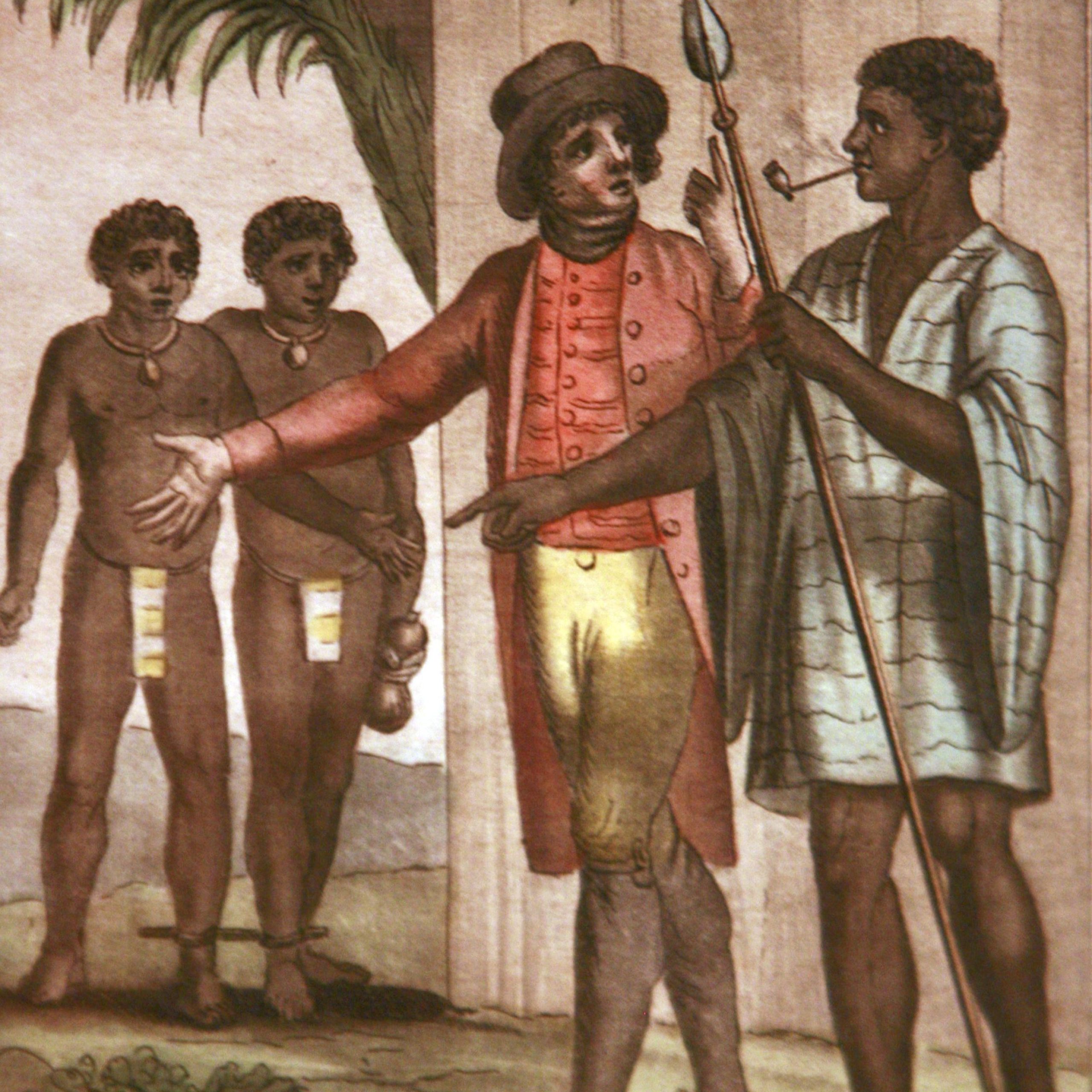

In 1441, Portuguese explorers Antão Gonçalves and Nuno Tristão, under the patronage of Prince Henry the Navigator, reached the Cape Blanco area (modern-day Mauritania) on an expedition initially aimed at obtaining gold and ivory. However, this journey marked a critical turning point: the Portuguese captured several Africans and brought them back to Portugal, where they were sold as slaves.

These initial captures were not part of a systematic plan but were driven by opportunism and the explorers’ desire to demonstrate the profitability of their missions. These captives, often taken during raids or through coercion, were among the first Africans forcibly transported to Europe to serve as enslaved laborers.

The success of this expedition encouraged further Portuguese ventures along the West African coast, eventually establishing a pattern of raiding and trading human lives. Over time, these expeditions evolved into an organized trade network. The introduction of African slaves into European markets in the mid-15th century laid the foundation for the transatlantic slave trade, which would expand dramatically in the following centuries.

1455: Papal bull “Romanus Pontifex”

In 1455, Pope Nicholas V issued the papal bull Romanus Pontifex, a critical document that granted Portugal exclusive rights to explore, conquer, and exploit territories inhabited by non-Christians. The decree explicitly authorized the enslavement of “Saracens, pagans, and any other unbelievers,” effectively legitimizing Portugal’s actions along the African coast.

This papal endorsement provided a religious justification for slavery and colonization, aligning them with the goal of spreading Christianity. The bull served as the ideological backbone for Portugal’s maritime expansion and the enslavement of African peoples. It also fostered the development of a racial and cultural hierarchy that framed Europeans as superior and Africans as subjects to be exploited.

Romanus Pontifex not only emboldened Portuguese explorers but also set a precedent for other European powers. By framing conquest and enslavement as a divine mission, the document embedded systemic racism and dehumanization into the fabric of European colonialism, with far-reaching consequences for global history.

1481: Founding of Elmina Castle

In 1481, King John II of Portugal ordered the construction of a permanent trading post on the Gold Coast, in what is now modern Ghana. Completed in 1482, São Jorge da Mina (Elmina Castle) became Portugal’s first permanent settlement in Sub-Saharan Africa. While its initial purpose was to facilitate the gold trade, Elmina quickly transitioned into a hub for the burgeoning transatlantic slave trade.

The castle included storage rooms, residential quarters for Portuguese merchants, and underground dungeons where captives were held before being shipped to the Americas. Its design reflected the dual priorities of economic exploitation and military defense, as it was fortified against potential attacks from rival European powers or African forces.

rElmina Castle epitomized the commodification of human lives. Over the centuries, hundreds of thousands of Africans passed through its gates, enduring inhumane conditions before being forced onto slave ships. The site remains a stark symbol of the atrocities of the slave trade and the enduring legacy of European colonialism in Africa.

1488: The Cape of Good Hope

In 1488, Portuguese explorer Bartolomeu Dias rounded the Cape of Good Hope at Africa’s southern tip for the first time. This daring expedition opened maritime links between Europe and Asia without passing through lands controlled by the Ottomans and other Muslim powers. Although the initial goal was to find a route to the rich spice markets of India, this discovery enhanced Portuguese navigators’ capabilities and stimulated trade with sub-Saharan Africa.

Rounding the Cape of Good Hope was a crucial step in building a global commercial empire for Portugal. Contacts with Africa’s eastern coasts also extended the slave trade. Africa thus became a hub for supplying labor to Portuguese colonies in Asia and later to the Americas.

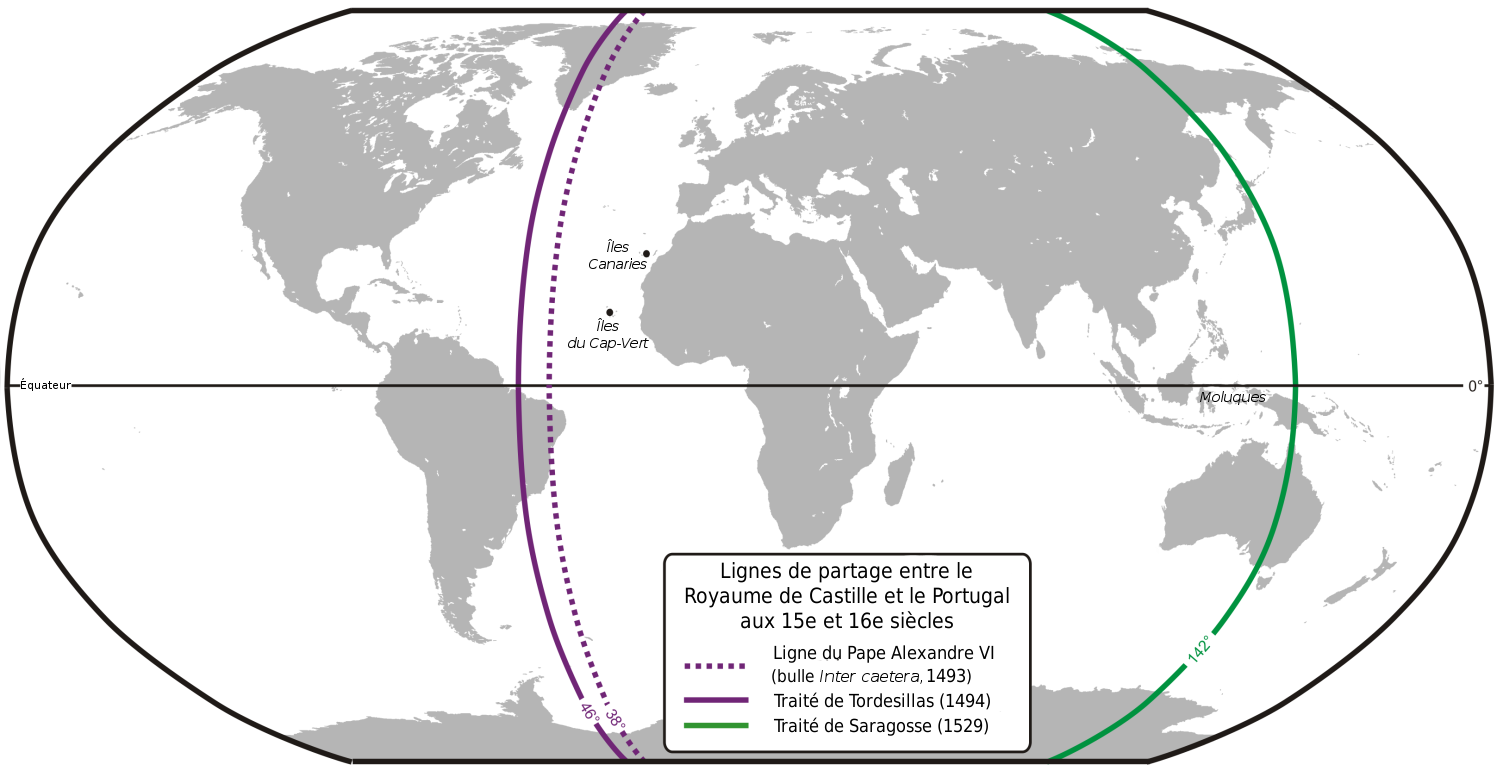

1494: Treaty of Tordesillas

The Treaty of Tordesillas, signed on June 7, 1494, was an agreement between Spain and Portugal, brokered by Pope Alexander VI, to divide the newly “discovered” non-European territories. The treaty established a demarcation line approximately 370 leagues west of the Cape Verde Islands. Lands to the west of this line were allocated to Spain, while those to the east were reserved for Portugal.

This treaty reflected the competitive nature of European exploration and colonization in the late 15th century. For Portugal, the agreement secured its claims over the African coasts, the Indian Ocean routes, and eventually Brazil. For Spain, it granted dominance over the Americas.

The Treaty of Tordesillas facilitated the expansion of European empires but also institutionalized the exploitation of African and indigenous peoples. It cemented Portugal’s control over the African slave trade, which would supply labor to the colonies of both powers for centuries. By dividing the world without consideration for its inhabitants, the treaty laid the groundwork for the systematic exploitation of non-European lands and peoples.

Late 15th century: The “Discoveries” of the Americas and the rowing demand for labor

The “discovery” of the Americas by Christopher Columbus in 1492 opened a new chapter in world history. The new lands explored by the Spanish and Portuguese, such as the Caribbean islands, Central America, and South America, offered abundant natural resources, notably precious metals and lands suitable for agriculture.

However, exploiting these riches required significant labor. Indigenous populations, subjected to extreme working conditions, were rapidly decimated by diseases brought from Europe, against which they had no immunity, as well as by mistreatment. Faced with this demographic catastrophe, European colonists sought to fill the void by importing African slaves.

The idea of using African labor then gained momentum. Africans were perceived as more resistant to tropical diseases and less likely to escape in unfamiliar environments. The establishment of maritime routes between Africa and the Americas intensified to meet this growing demand. The Portuguese, with their experience in Africa, played a key role in supplying slaves to the Spanish and Portuguese colonies in the New World.

Early 16th century: Local alliances and complicities

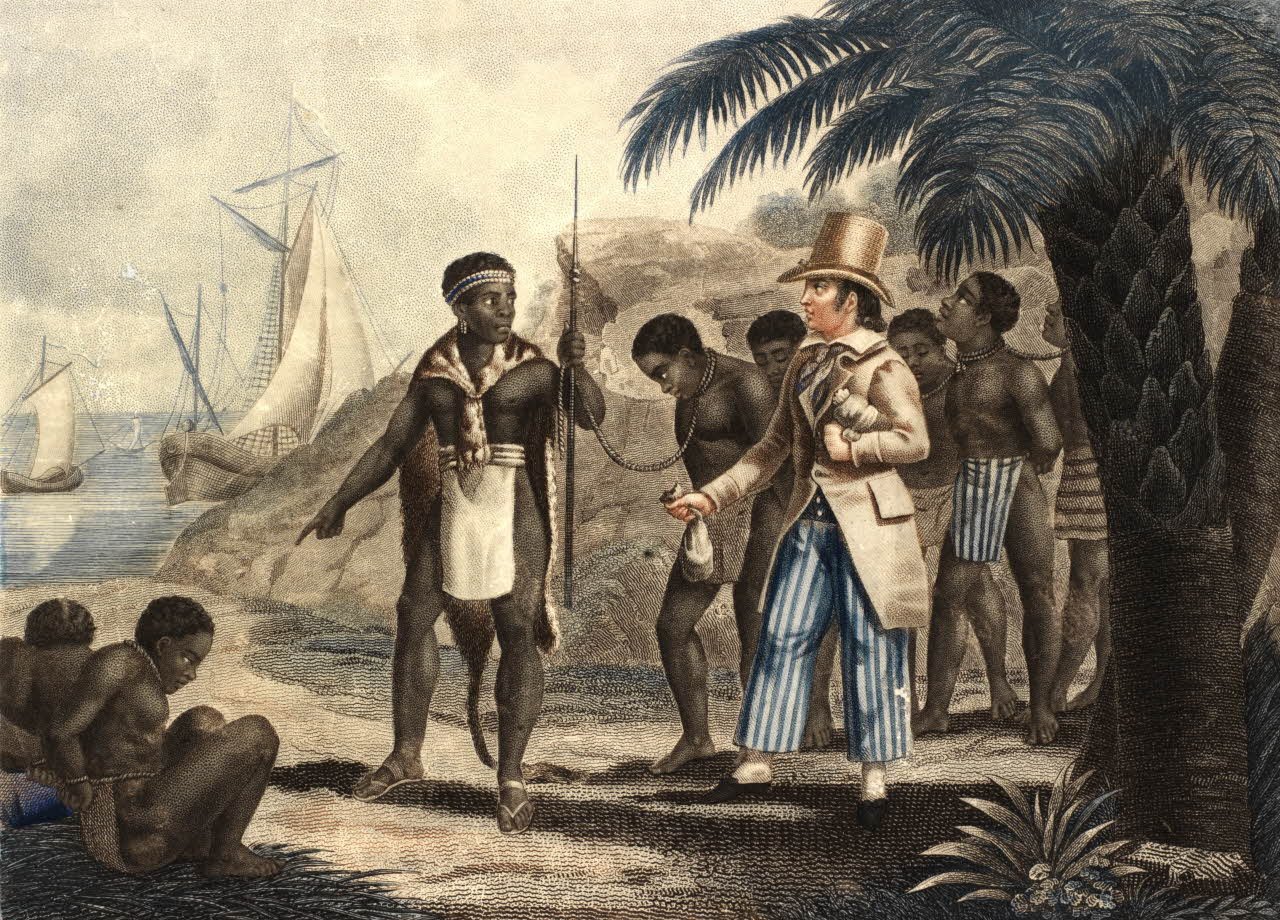

In the early 16th century, Europeans, particularly the Portuguese, established trade relations with certain coastal African kingdoms, such as the Kingdom of Kongo and the Kingdom of Benin. These alliances, sometimes established under pressure or through unequal treaties, allowed the Portuguese to obtain captives for the slave trade.

Some African elites participated in this trade, either to obtain European goods like weapons, textiles, alcohol, or to strengthen their political and military power against local rivals. However, this collaboration was complex and often ambivalent. Many African societies resisted the trade and suffered raids, betrayals, and violence from Europeans.

These complicities, even limited, facilitated the structuring of the trade in West Africa. They led to intensified capture wars, political destabilizations, and interethnic conflicts fueled by European demand for slaves. The social and political fabric of many African regions was profoundly affected by this trade, leading to lasting consequences on African societies.

The beginnings of slavery ideology in Europe

Writings by some European explorers, missionaries, and intellectuals contributed to developing an ideology justifying the enslavement of Africans. In 1453, Portuguese chronicler Gomes Eanes de Zurara, commissioned by Prince Henry the Navigator, wrote the “Chronicles of the Discovery and Conquest of Guinea.” He described Africans as “pagans” in need of conversion, presenting their capture as an act of Christian charity and civilization.

These accounts propagated a dehumanizing image of Africans in Europe, reinforcing racial prejudices and stereotypes. The idea of cultural, religious, and soon racial superiority of Europeans was used to legitimize the exploitation and trade of Africans. This ideology would be reinforced later, notably with the development of the concept of “race” in the 18th century, supporting the slave system for centuries.

The caravel and navigational innovations

The invention of the caravel in the mid-15th century was a major technological advancement that facilitated exploration and maritime trade. This lighter and more maneuverable ship, equipped with lateen triangular sails and later square sails, allowed navigators to sail against the wind and navigate the high seas more safely.

Innovations in cartography, such as the use of the magnetic compass, astrolabe, and quadrant, as well as advances in astronomical navigation, enabled sailors to determine their position at sea with increased accuracy. These technological developments were essential to the sustainability of the transatlantic trade, offering safer and faster means to transport African captives to the Americas.

Explorations led by navigators like Vasco da Gama, who reached India by rounding Africa in 1498, demonstrated the possibilities offered by these innovations. They paved the way for global maritime trade, where Africa played a central role as a supplier of enslaved labor and resources.

II. Expansion of the trade (16th – 17th Centuries)

In the 16th and 17th centuries, the transatlantic trade rapidly developed under the impetus of European powers, motivated by the expansion of their colonies in the Americas and the growth of sugar, mining, and agricultural economies. Portugal and Spain were joined by England, France, and the Netherlands, competing for control of this extremely lucrative trade. The trade gradually became structured, institutionalized, and supported by maritime infrastructures, political alliances, and specific legislations, making slavery indispensable to colonial economies.

1518: Charles V authorizes the trade to spanish colonies

In 1518, Charles V, King of Spain and Holy Roman Emperor, issued a crucial decree officially authorizing the importation of captured Africans to Spanish colonies, notably in the Caribbean. This decree came in a context where indigenous populations in the Americas were decimated by European diseases, mistreatment, and forced labor, leading to a labor shortage for exploiting sugar plantations, gold, and silver mines.

By recognizing the trade of Africans as state policy, Charles V institutionalized slavery in Spanish colonies. He established the asientos, royal contracts granting individuals or companies the exclusive right to supply slaves to Spanish colonies. Portuguese merchants, ahead in the African slave trade, became the main suppliers to Spanish colonies.

This decree marked a fundamental step in the expansion of the transatlantic trade, making Africans an essential and enduring resource for the Spanish colonial economy. It laid the foundations of an economic system where human exploitation was legalized and encouraged by the state, deeply embedding the slave system in colonial structures.

1562: First English slave expedition

In 1562, English merchant and navigator John Hawkins organized the first English slave-trading expedition. With the tacit support of Queen Elizabeth I, Hawkins captured about 300 Africans on the coasts of Sierra Leone, often by force or exploiting local conflicts. He then transported them to the Spanish colonies in the Caribbean, where he sold them as slaves in exchange for pearls, hides, and sugar.

The financial success of this expedition prompted Hawkins to organize further voyages, making him the pioneer of English slave trading. His expeditions attracted the attention of many investors and marked England’s official entry into the transatlantic slave trade. Hawkins adopted a commercial model combining piracy, illegal trade (since the Spanish prohibited foreigners from trading with their colonies), and slave trading, setting a precedent for future English merchants.

These expeditions helped strengthen commercial ties between England and the New World colonies while consolidating a lucrative model that would stimulate British participation in the trade. They laid the groundwork for England’s increasing involvement in the trade of African captives, which would become a major component of its colonial empire.

1571: Development of sugar plantations in Brazil

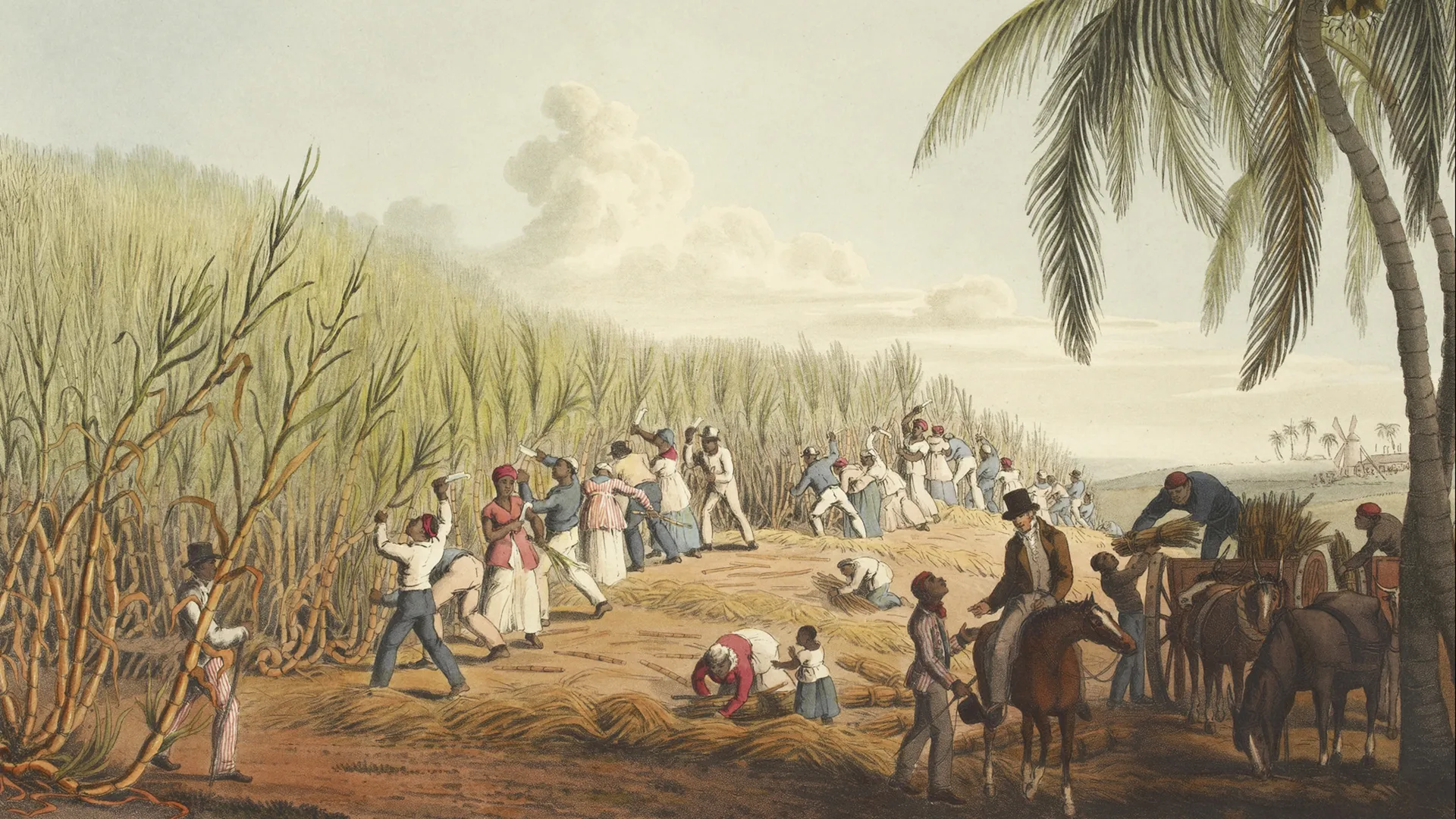

Starting in 1571, Portugal implemented an ambitious colonial strategy in northeastern Brazil, notably in the regions of Bahia and Pernambuco. The vast fertile lands of these regions were ideal for cultivating sugar cane, a highly prized commodity in Europe.

To exploit these plantations, the Portuguese massively resorted to enslaved African labor. Captives were imported mainly from Angola, Congo, and Mozambique. Work on the sugar plantations was extremely arduous and dangerous, involving long hours under tropical climates, risks of accidents with sugar mills, and severe discipline.

Brazil quickly became the world’s leading sugar producer, supplying the European market and generating considerable profits for Portuguese colonists. This plantation model relied on total dependence on the forced labor of African slaves, establishing an economic and social system based on exploitation and racial segregation.

The economic success of Brazilian sugar plantations influenced other European colonies, which adopted similar models in the Caribbean and North America. The development of these plantations intensified the transatlantic trade, establishing commercial networks of unprecedented scale and reinforcing the idea of slavery as a pillar of colonial economies.

1619: The first African slaves in Virginia

In 1619, a Dutch ship, the White Lion, docked at Jamestown, Virginia, bringing with it about twenty captured Africans, initially taken from a Portuguese slave ship. These individuals were sold to English colonists and forced to work on tobacco plantations.

This event marked the official introduction of African slavery into the English colonies of North America. Unlike European indentured servants, who could hope for freedom after a determined period, these Africans had no prospects of liberation or civil rights. Their status was ambiguous at first, but over time, the colonies adopted laws codifying hereditary slavery based on race.

The growing need for labor for tobacco, then cotton and rice cultivation, favored the rapid expansion of slavery in the American colonies. Slavery became a central element of the colonial economy and contributed to the economic rise of the southern colonies. This rise was accompanied by the development of a society founded on racial segregation and white supremacy, whose effects would persist well beyond the abolition of slavery.

1620 – 1640: Creation of European trading companies

Between 1620 and 1640, several European powers created trading companies to monopolize trade with Africa and the Americas. Among the most notable were:

- The Dutch West India Company (WIC), founded in 1621 by the Netherlands, which obtained a monopoly on trade with West Africa, the Americas, and the Caribbean.

- The French West India Company, created in 1664 under the impetus of Colbert, minister of Louis XIV, aiming to develop French trade in the colonies.

These companies played a major role in industrializing the transatlantic trade. They established trading posts and forts along the African coasts, such as Gorée, Saint-Louis, and Ouidah, to facilitate the slave trade and secure their interests against competition.

The triangular trade system was established:

- Europe to Africa: Ships transported manufactured goods (weapons, textiles, alcohol) to exchange for African captives.

- Africa to the Americas: Captives were transported to the colonies during the Middle Passage under inhumane conditions.

- Americas to Europe: Ships brought back colonial raw materials (sugar, tobacco, cotton, coffee) to supply European markets.

This system intensified the deportation of Africans and transformed the global economy by integrating the three continents into an interdependent commercial network. European companies accumulated considerable profits, fueling nascent capitalism and financing wars and colonial expansions.

1642: Foundation of the Company of Royal Adventurers Trading to Africa

In 1642, King Charles I of England founded the Company of Royal Adventurers Trading to Africa, granting this entity a monopoly over the slave trade and precious goods in West Africa. The company established trading posts and forts, notably on the Gold Coast (present-day Ghana), to secure its operations.

The company played a crucial role in the systematic organization of the trade by the English. It facilitated the transportation of African captives to English colonies in the Caribbean and North America, strengthening the English presence in the transatlantic trade.

The direct involvement of the English state in this enterprise marked an important step in the industrialization of human trafficking. The company had its own ships, crews, and installations, allowing it to effectively control the slave trade and maximize profits. This organization surpassed mere dispatch of merchant ships, creating a commercial and military infrastructure dedicated to human exploitation.

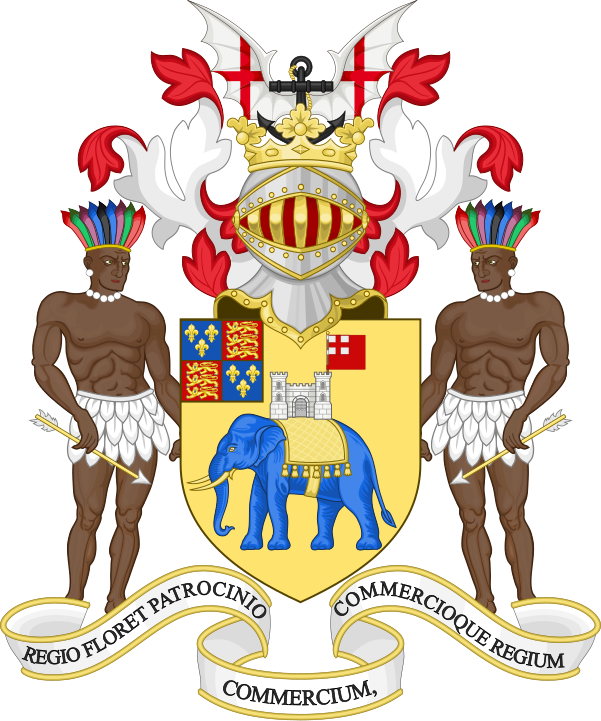

1672: Creation of the Royal African Company in England

n 1672, under the reign of Charles II, England founded the Royal African Company, which received the monopoly over the African slave and gold trade for English colonies. The company was led by the Duke of York, the future King James II, highlighting the highest level of state involvement in the trade.

The Royal African Company significantly increased the volume of deported captives through a dedicated fleet and reinforced fortifications along the African coasts. It established new forts, like Cape Coast Castle, and improved existing facilities to store captives before embarkation.

The profits generated by this trade reinforced England’s economic position and stimulated the expansion of its colonies. The company played a central role in financing national and military projects, contributing to the rise of the English navy.

By providing a military and logistical infrastructure to the trade, the Royal African Company gave slavery an industrial dimension. It created a strong economic dependence of the colonies on slave labor while consolidating England’s position as one of the world’s leading slave-trading powers.

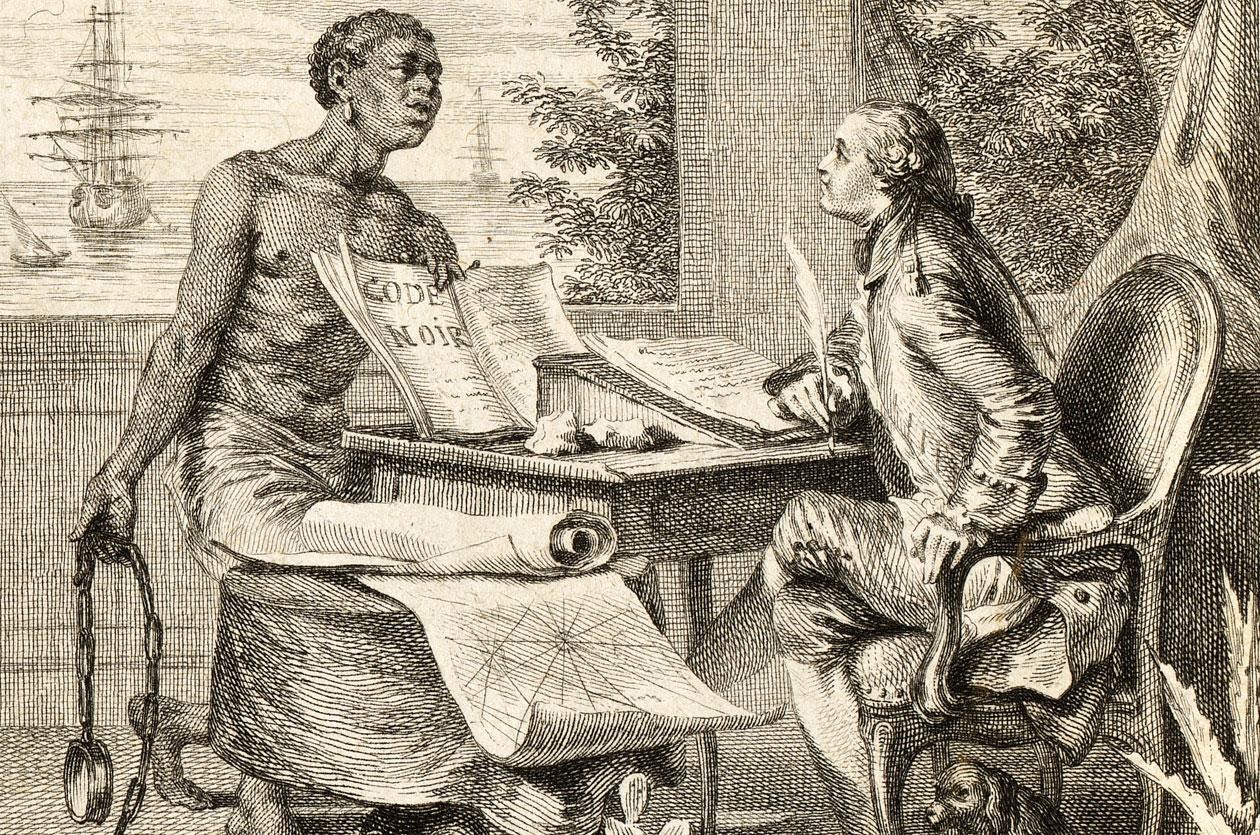

1685: The “Code Noir” in France

In 1685, King Louis XIV promulgated the “Code Noir” (Black Code), a collection of 60 articles regulating slavery in French colonies, notably the Antilles. Drafted under the supervision of Colbert, minister of Louis XIV, this code aimed to define the rights and duties of slaves and their masters, as well as to regulate daily life in the colonies.

The “Code Noir”:

- Institutionalized slavery by establishing a precise legal framework.

- Imposed Catholic baptism on slaves, justifying exploitation under the guise of “Christianization.”

- Set conditions for slaves’ work and life, including authorized corporal punishments.

- Prohibited slaves from carrying weapons, gathering in groups, or practicing their original religion.

- Regulated relations between masters and slaves, including marriages and recognition of mixed-race children.

The “Code Noir” reinforced the religious and legal legitimacy of the trade and slavery. It served as a model for other European colonies, solidifying the exploitation of Africans and consolidating a social system based on racial hierarchy. This code had lasting consequences on the structuring of French colonial societies and racial relations.

1698: End of the Royal African Company’s Monopoly

In 1698, under pressure from independent merchants and parliamentarians, England decided to end the Royal African Company’s monopoly. The Parliamentary Act now allowed any Englishman to trade with Africa, provided they paid a 10% tax for the maintenance of African forts.

This liberalization of trade stimulated the participation of many private merchants, known as “interlopers.” The number of English ships involved in the trade increased significantly, from about ten to over a hundred per year at the beginning of the 18th century.

English colonies in the Americas and the Caribbean received a continuous flow of African captives, intensifying the colonies’ dependence on slavery. England then became the dominant nation in the transatlantic slave trade, surpassing Portugal and the Netherlands.

This market opening marked the peak of British slave trading, with tens of thousands of Africans captured and transported each year. The profits generated helped finance the Industrial Revolution in England, reinforcing its economic and military power.

III. The apex of the Trade (18th Century)

The 18th century represents the culmination of the transatlantic slave trade, characterized by unprecedented intensity in the trade of African slaves. This century saw the industrialization of the triangular trade, the expansion of plantations in the Americas, and the emergence of the first abolitionist movements, marking both the peak and the beginning of the decline of the slave trade.

1700 – 1800: Millions of Africans deported

During the 18th century, it is estimated that over 12.5 million Africans were captured and deported to the Americas. Methods of capture intensified and became systematic, involving organized raids, interethnic wars fueled by European merchants, and forced or voluntary complicity with some African chiefs. European slave traders provided firearms and other goods in exchange for captives, exacerbating local conflicts.

Once captured, Africans were forced to march long distances to the coasts, often chained to one another. Conditions were harsh, and many perished en route. Upon arrival at coastal forts like Gorée, Ouidah, or Elmina, they were detained under inhumane conditions while awaiting embarkation.

The “Middle Passage,” the transatlantic crossing, was marked by atrocious conditions. Captives were crammed into the holds of slave ships, with no room to move, in suffocating heat and deplorable hygiene. Mortality was extremely high, estimated between 15% and 20%, due to overcrowding, diseases like dysentery or scurvy, malnutrition, dehydration, and mistreatment by the crew. Some captives committed suicide to escape their fate, while others attempted rebellions, often brutally suppressed.

Despite these considerable human losses, the trade became a pillar of the European colonial economy. African captives were sold in American markets and became the indispensable labor force for plantations of sugar, tobacco, cotton, coffee, and other lucrative crops. The profits generated by this human exploitation enriched European powers, notably Great Britain, France, the Netherlands, Portugal, and Spain, and fueled their economic expansion, allowing them to finance the Industrial Revolution and increase their global influence.

1713: The British monopoly with the “Asiento de Negros”

The Treaty of Utrecht in 1713, ending the War of the Spanish Succession, redrew the power map in Europe and had major repercussions on the transatlantic trade. Spain granted Great Britain the monopoly of supplying slaves to the Spanish colonies in South America, known as the “Asiento de Negros.” This strategic agreement allowed the British to dominate the slave trade, strengthening their maritime and commercial power.

To manage this monopoly, the South Sea Company was created in 1711, although the monopoly was granted in 1713. The company increased the number of British ships transporting African captives to Spanish colonies, profiting from this lucrative trade. This exclusivity amplified the scale of the trade and helped make Great Britain the principal actor in the slave trade in the 18th century. The revenues generated by the Asiento contributed to British economic prosperity and financed its national debt.

1725: Strengthening of Black Codes in Louisiana

In 1724, Louisiana, then a French colony, introduced a specific “Code Noir” to regulate slavery. This code, promulgated by Governor Bienville, reinforced previous laws and strictly defined the rights of masters and duties of slaves. It severely limited slaves’ freedoms, prohibited marriage between people of different races, imposed the Catholic religion, and instituted brutal punishments for any act of rebellion or insubordination. The Louisiana Code Noir continued the 1685 Code Noir promulgated by Louis XIV but with even stricter restrictions, reflecting the colonies’ growing dependence on slavery for economic development. It institutionalized the slave system and codified racial hierarchy within colonial society.

1739: The Stono rebellion in South Carolina

On September 9, 1739, the Stono Rebellion broke out in South Carolina, one of the largest slave insurrections in British North American colonies before the American Revolution. About 20 African slaves, mainly from the Kingdom of Kongo and Portuguese-speaking, were led by a man named Jemmy. They seized weapons from a warehouse, killed white colonists, and encouraged other slaves to join them in their march to Spanish Florida, where freedom was promised in exchange for conversion to Catholicism.

The group grew to about 100 people before being confronted by the colonial militia. The rebellion was violently suppressed, with many rebels killed and survivors captured, who were executed or sold to the Caribbean. The rebellion provoked intense fear among colonists and led to the adoption of the Negro Act of 1740, legislation that further restricted slaves’ rights, banning education, gatherings, and severely limiting their mobility. This revolt highlighted slaves’ desperation under oppressive conditions and their willingness to resist.

1760: Slave rebellions in Jamaica (Maroon Wars)

In the 1760s, Jamaica was the scene of several major rebellions by Maroon slaves, descendants of Africans who had escaped plantations to establish free communities in mountainous regions. In 1760, the rebellion led by Tacky, a former African chief probably from the Fante kingdom (present-day Ghana), mobilized hundreds of slaves. They attacked plantations, seized weapons and supplies, and killed colonists. The rebellion spread rapidly, threatening colonial stability.

Although ultimately crushed by British colonial forces, with the help of colonist militias and other slaves, Tacky’s rebellion demonstrated persistent slave resistance and posed a constant threat to colonial order. These insurrections forced authorities to negotiate treaties with the Maroons, recognizing their autonomy in exchange for their help in suppressing future rebellions. The Maroon rebellions also influenced colonial policies on security and slave management.

1772: Somerset case and first judicial decision in England

In 1772, the Somerset v Stewart case marked an important legal milestone in the history of slavery in England. James Somerset, an African slave purchased in Virginia by Charles Stewart, was brought to London by his master. Somerset escaped but was captured and forcibly placed on a ship bound for Jamaica to be sold. The case was brought before the British judiciary by abolitionists, and Judge Lord Mansfield was tasked with ruling.

In his decision, Lord Mansfield declared that slavery was not recognized by English law and that Somerset must be freed. Although the judgment was specific to Somerset’s case and did not abolish slavery in the British Empire, it established a significant precedent. This decision encouraged the abolitionist movement in England, questioned the legality of slavery on English soil, and sparked debates on slaves’ rights and the morality of slavery.

1781: The Zong Massacre

In November 1781, the British slave ship Zong, commanded by Captain Luke Collingwood, sailed toward Jamaica with about 440 African captives on board, well beyond its capacity. Facing a shortage of potable water due to a navigational error and disease spreading among captives and crew, Collingwood ordered 133 sick or dying African slaves to be thrown overboard. He hoped to claim compensation from the insurance company for the “loss” of his “cargo,” arguing that the slaves were jettisoned to save the ship.

When the case was brought to court in 1783, it was initially treated as a simple maritime insurance matter. However, the details of the massacre provoked public outrage. The Zong incident became a catalyst for the British abolitionist movement. Figures like Granville Sharp used this tragedy to denounce the barbarity of the slave trade and mobilize public opinion against slavery. The case highlighted the atrocities committed during the slave trade and intensified calls for abolition.

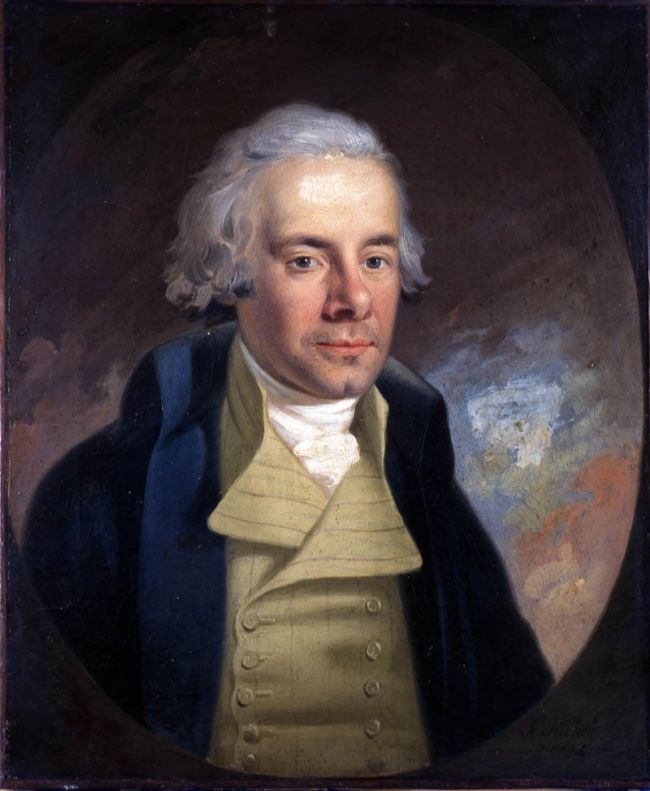

1787: Foundation of the society for effecting the abolition of the slave trade

In May 1787, the Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade was founded in London by a group of 12 men, including Thomas Clarkson and Granville Sharp. Composed mainly of Quakers and Anglicans, the organization aimed to raise public awareness of the horrors of the trade and lobby the British Parliament for its abolition. The society launched a national campaign, using pamphlets, petitions, testimonies from former slaves like Olaudah Equiano, and shocking images, such as the plan of the slave ship Brookes, to illustrate the inhumane conditions of the trade.

Their actions marked the beginning of an organized abolitionist movement. The society collected thousands of signatures, organized public meetings, and collaborated with sympathetic parliamentarians like William Wilberforce. Their work helped change public opinion and create political pressure in favor of abolition.

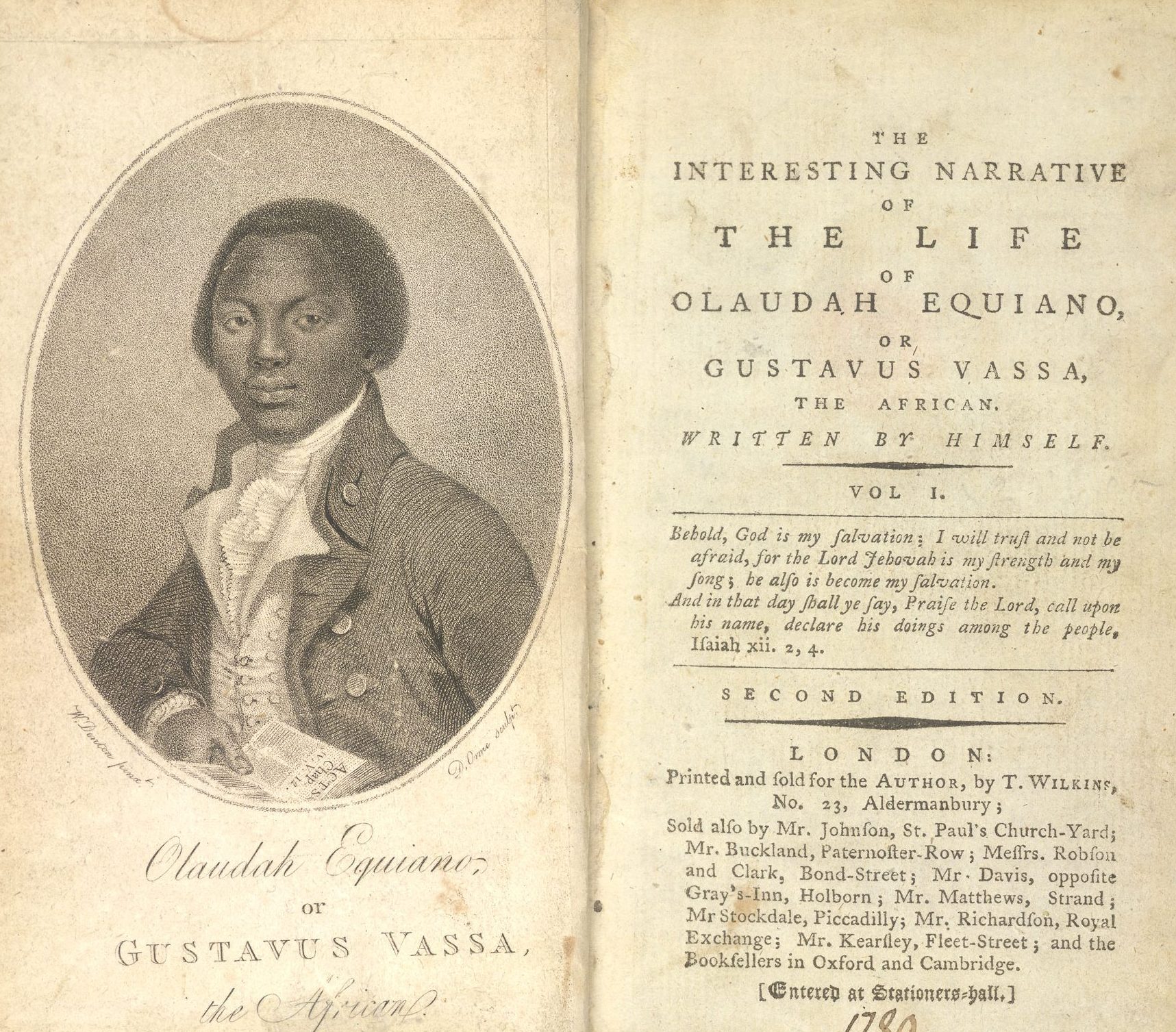

1789: Publication of “The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano”

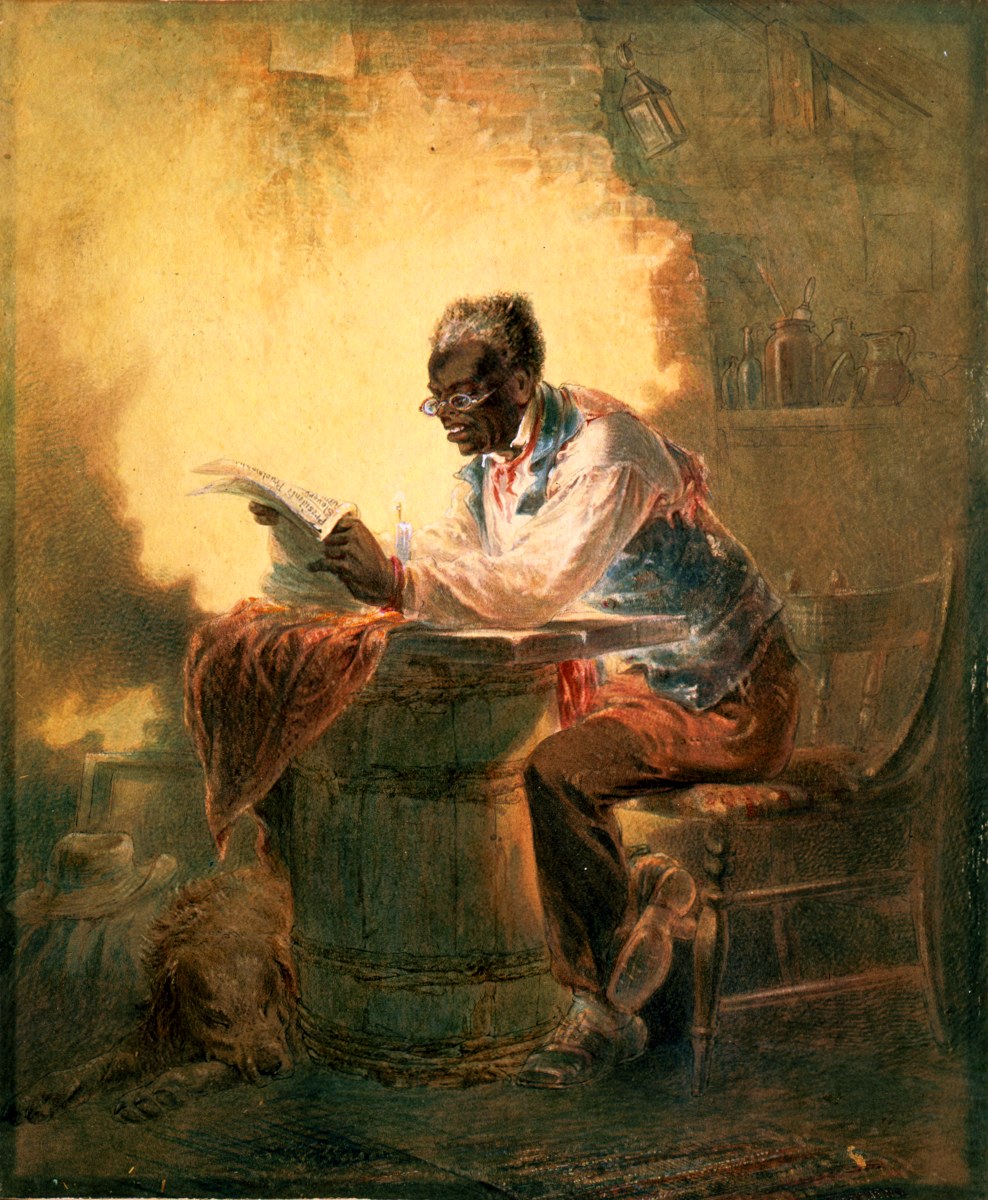

In 1789, Olaudah Equiano, also known as Gustavus Vassa, published his autobiography titled “The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano.” Born in West Africa, probably in the Kingdom of Benin (present-day Nigeria), Equiano was captured at age 11 and sold into slavery. His account describes his abduction, the horrors of the trade, his life as a slave, and eventually his journey to freedom after purchasing his own emancipation.

The book became a bestseller in England and was translated into several languages. It provided a poignant personal testimony of the sufferings endured by slaves, humanized the victims of the trade, and strengthened abolitionist arguments. Equiano used his narrative to denounce the hypocrisy of European Christians involved in the trade and called for immediate abolition. His work influenced public opinion and played a crucial role in the abolitionist movement.

1790: Beginning of debates on abolition in the British Parliament

In 1790, the British Parliament officially began debates on abolishing the slave trade. Under the impetus of the Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade and parliamentarians like William Wilberforce, in-depth discussions examined moral, economic, and humanitarian arguments against the trade. Wilberforce presented a bill aiming to abolish the trade, supported by testimonies, evidence, and petitions.

These debates were marked by strong opposition from plantation owners, traders, and some MPs defending economic interests linked to the trade. Despite obstacles, these discussions marked a turning point in the abolitionist struggle, further sensitizing Parliament and laying the groundwork for future legislation. Although the bill was not immediately adopted, the movement gained momentum.

1791: The Haitian Revolution, an emblematic revolt

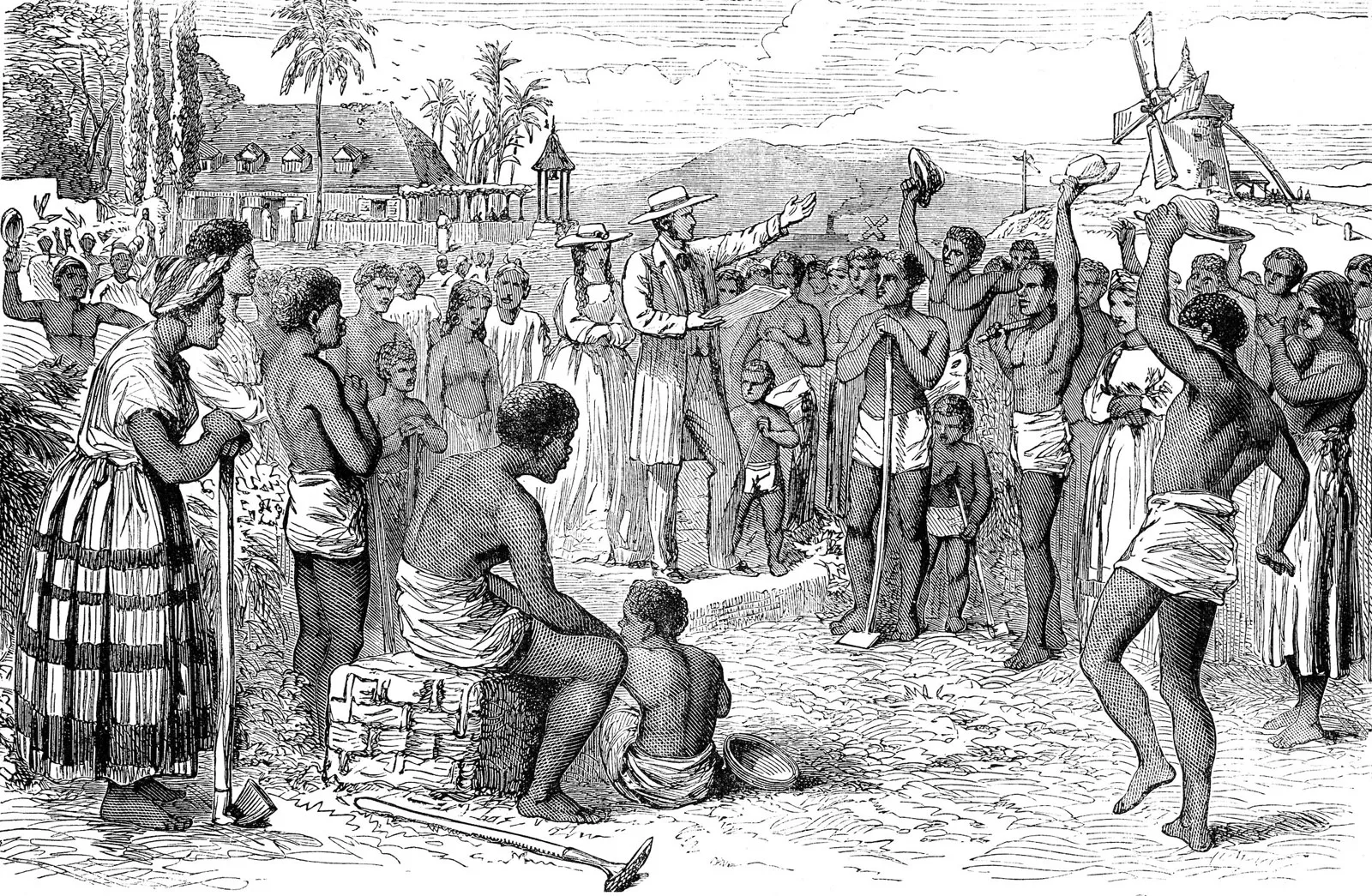

On August 22, 1791, a slave revolt broke out in Saint-Domingue, France’s richest Caribbean colony, producing half the sugar and coffee consumed in Europe. Led by figures like Toussaint Louverture, Jean-Jacques Dessalines, and Henri Christophe, the insurrection was sparked by the inhumane conditions of slavery and inspired by the ideals of liberty and equality from the French Revolution of 1789.

The rebellion transformed into a war of liberation lasting over ten years, involving clashes between slaves, white colonists, free mulattoes, and the French, Spanish, and British armies. In 1804, after defeating Napoleonic forces, Saint-Domingue declared its independence under the name Haiti, becoming the world’s first free Black republic and the first state born from a successful slave revolt.

The Haitian Revolution shook the global slave system, frightened colonial powers, and inspired abolitionist movements worldwide. It demonstrated slaves’ capacity to free themselves by force and questioned the legitimacy of slavery. However, Haiti was diplomatically and economically isolated, subjected to a blockade, and had to pay an exorbitant indemnity to France for recognition, which would durably affect its development.

1792: Denmark’s “Gradual Prohibition Act”

In 1792, Denmark-Norway became the first European nation to adopt a law aiming to abolish the slave trade. The law, effective in 1803, prohibited Danish participation in the transatlantic slave trade. Although partly motivated by economic and strategic considerations, this pioneering decision also reflected moral and humanitarian awareness. Denmark’s action set an international precedent and pressured other European powers to reconsider their involvement in the trade.

1793: The French Convention abolishes slavery for the first time

On February 4, 1794 (16 Pluviôse Year II), the French National Convention decreed the abolition of slavery in all French colonies, in response to the uprisings in Saint-Domingue and under the influence of revolutionary ideals of liberty and equality. This radical measure was the first legal abolition of slavery on a national scale. However, the application of this law was limited and contested, notably in colonies where colonists resisted its implementation. In 1802, Napoleon Bonaparte reinstated slavery to appease colonists and revive the sugar economy, nullifying the Convention’s advances. Nevertheless, this first abolition marked an important step in abolitionist history and highlighted contradictions between revolutionary principles and economic interests.

This period of the 18th century was characterized by extreme intensification of the slave trade, supported by colossal economic interests and established legal structures. However, it was also the century where significant resistances emerged, both from the slaves themselves and from abolitionist movements in Europe and America. Rebellions, publications, political debates, and judicial decisions contributed to shaking the moral and legal foundations of the trade, preparing the ground for its gradual abolition in the following century.

IV. The first prohibitions and gradual abolition (19th Century)

The 19th century was marked by growing awareness of the horrors of the slave trade and slavery, fueled by increasingly influential abolitionist movements in Europe and America. Despite economic and political resistance, several nations adopted laws to prohibit the slave trade, initiating a slow transition toward total abolition of slavery.

1807: Prohibition of the trade in the United Kingdom

On March 25, 1807, the Slave Trade Act was passed by the British Parliament, officially prohibiting the slave trade in the British Empire. This success was the result of years of campaigning by abolitionists such as William Wilberforce, Thomas Clarkson, and the Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade.

The Slave Trade Act did not end slavery itself, which persisted in British colonies, but it marked a crucial step in the fight against the transatlantic slave trade. The law prohibited British ships from participating in the trade and provided penalties for violators. The United Kingdom, then the dominant maritime power, also began pressuring other nations to abolish the trade.

To enforce the prohibition, the Royal Navy established a dedicated squadron, the West Africa Squadron, tasked with patrolling African coasts and intercepting slave ships. Between 1808 and 1860, this squadron captured about 1,600 ships and freed 150,000 Africans. However, despite these efforts, illegal trade continued, with merchants using foreign flags or evasion techniques to pursue their lucrative activities.

1808: The United States follows Suit

On January 1, 1808, the United States officially prohibited the transatlantic slave trade, in accordance with a clause of the U.S. Constitution allowing Congress to legislate on this subject after 1808. President Thomas Jefferson, himself a slave owner, signed the law ending the importation of slaves into the United States.

However, slavery as an institution persisted in the U.S., notably in southern states where the economy heavily depended on slave labor in cotton, tobacco, and sugar plantations. The ban on international trade led to an increase in the domestic slave trade, with the forced relocation of hundreds of thousands of African Americans from the Upper South to the Deep South.

Furthermore, the prohibition fueled clandestine routes and illegal trafficking. Ships continued to secretly import slaves from Africa despite the risks involved. American authorities, while having legislated against the trade, were often lax in enforcing the law due to political and economic pressures from slaveholding states.

1833: Abolition of slavery in the British Empire

On August 28, 1833, the British Parliament passed the Slavery Abolition Act, abolishing slavery in most of the British Empire. This law took effect on August 1, 1834, freeing over 800,000 slaves in British colonies in the Caribbean, Africa, and Canada.

The abolition was the result of decades of abolitionist campaigning, marked by petitions, demonstrations, and the work of activists such as William Wilberforce, Thomas Clarkson, Olaudah Equiano, and Granville Sharp. The movement was supported by a public increasingly sensitive to moral and religious arguments against slavery.

However, the law provided for an apprenticeship period of four to six years, during which former slaves had to continue working for their former masters for a token remuneration. This measure provoked discontent and protests among the freed people. Eventually, the apprenticeship system was abandoned in 1838.

Slave owners received financial compensation of £20 million, a colossal sum at the time, representing about 40% of the national budget. The slaves, meanwhile, received no compensation for the sufferings endured.

1848: France abolishes slavery in Its colonies

On April 27, 1848, the provisional government of the French Second Republic adopted a decree definitively abolishing slavery in all its colonies. This decision is largely attributed to the actions of Victor Schœlcher, Under-Secretary of State for the Navy and Colonies, a fervent abolitionist.

After a first abolition in 1794 by the National Convention, slavery had been reinstated in 1802 by Napoleon Bonaparte to satisfy colonists and revive the sugar economy of the Antilles. The second abolition of 1848 thus marked the official end of slavery in French colonies, freeing about 250,000 slaves in Guadeloupe, Martinique, French Guiana, Réunion, and Senegal.

The 1848 decree was accompanied by measures to integrate former slaves into colonial society, notably by granting French citizenship. However, the transition was difficult, and freed people continued to face discrimination, precarious working conditions, and persistent social segregation.

V. The official end of the trade (Late 19th Century

The 19th century was marked by growing awareness of the horrors of the transatlantic slave trade and slavery, fueled by increasingly influential abolitionist movements in Europe and America. Despite economic and political resistance, several nations adopted laws to prohibit the slave trade, initiating a slow transition toward the total abolition of slavery.

1865: End of slavery in the United States

The American Civil War (1861-1865) pitted the industrialized, abolitionist Northern states against the agricultural, slaveholding Southern states. The conflict was largely centered on the issue of slavery and states’ rights.

On January 1, 1863, President Abraham Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation, declaring all slaves in rebellious Confederate states to be free. However, this proclamation did not apply to slaveholding states that remained loyal to the Union or areas already under Union control.

It was with the ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution on December 6, 1865, that slavery was definitively abolished in the United States. The amendment stated that “neither slavery nor involuntary servitude shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.”

This abolition marked the liberation of over four million African American slaves. However, the Reconstruction period that followed was marked by racial tensions, the implementation of Jim Crow laws, and the persistence of systemic discrimination against African Americans.

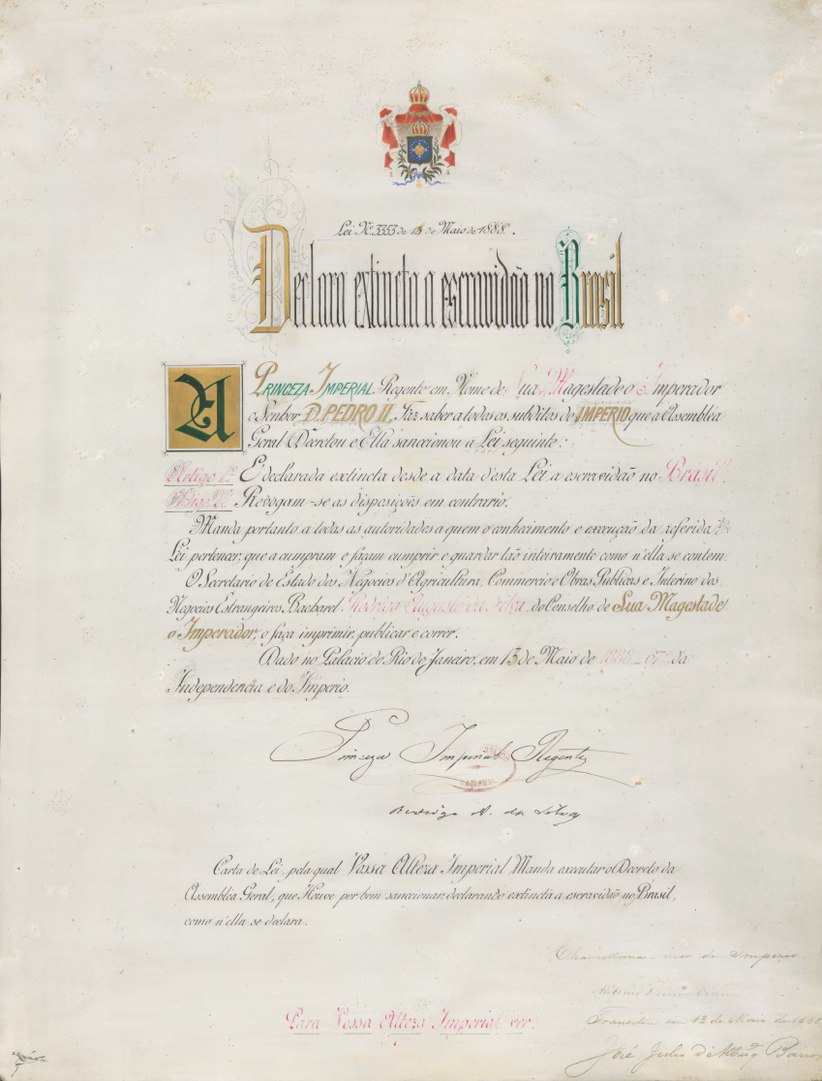

1888: Abolition of slavery in Brazil

On May 13, 1888, the Lei Áurea (Golden Law) was promulgated by Princess Isabel, daughter of Emperor Pedro II, abolishing slavery in Brazil. The last country on the American continent to abolish slavery, Brazil freed about 700,000 slaves, marking the official end of the transatlantic slave trade.

This abolition was the result of decades of internal and external pressure, slave revolts, escapes to quilombo communities (maroon villages), and campaigns led by abolitionists such as Joaquim Nabuco and José do Patrocínio.

The Brazilian economy, heavily dependent on slavery, notably in coffee and sugar plantations, underwent a major transformation. Former slaves were freed without compensation or assistance, facing poverty and marginalization.

International efforts to suppress the trade

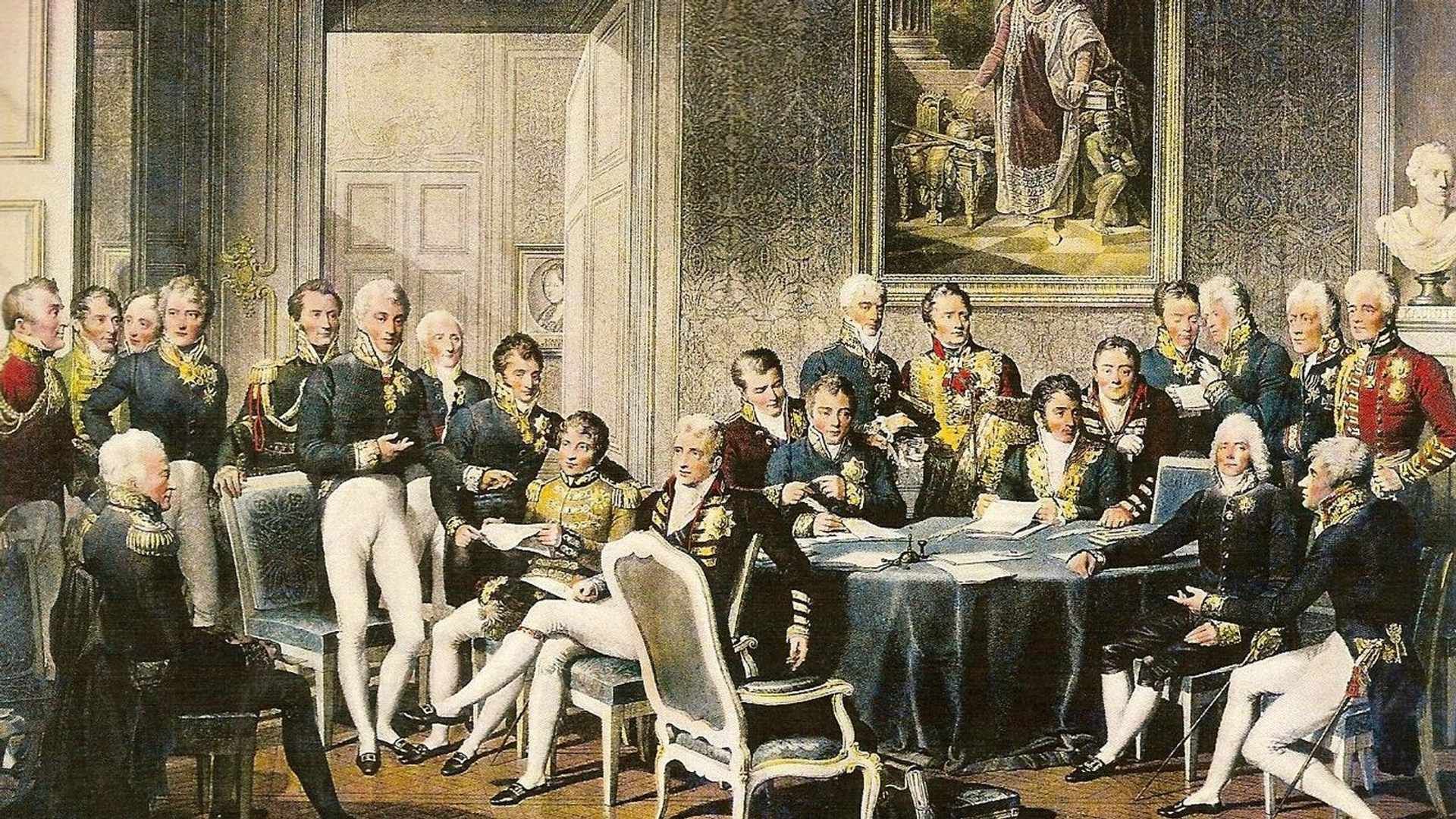

Throughout the 19th century, diplomatic efforts were made to end the slave trade. The United Kingdom signed bilateral treaties with several countries to prohibit the trade, and European powers met at international congresses.

At the Congress of Vienna in 1815, European nations condemned the slave trade, although without binding measures. In 1885, the Final Act of the Berlin Conference on the partition of Africa included provisions for suppressing the trade.

Despite these initiatives, illegal trade persisted, notably in East Africa and the Indian Ocean, fueled by markets in the Middle East and Asia. It was only at the beginning of the 20th century that the slave trade was almost eradicated, thanks to a combination of international pressure, naval surveillance, and economic changes.

Consequences and legacy of abolition

The abolition of slavery did not end inequalities and racial discrimination. In former colonies, societies remained marked by hierarchies inherited from slavery. Former slaves and their descendants faced economic, social, and political obstacles.

Coercive labor systems, such as indentured servitude or forced labor, were implemented to replace slave labor, often exploiting indigenous populations or immigrant contract workers.

Struggles for civil rights, equality, and social justice continued throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, carried by movements such as Pan-Africanism, the Civil Rights Movement in the United States, and anti-colonial struggles in Africa and the Caribbean.

Balance and consequences of the transatlantic slave trade

The transatlantic slave trade left a heavy legacy for African peoples and their descendants, with lasting consequences on Afro-descendant societies and global racial structures.

Demographic and social impact

The deportation of millions of young men and women weakened entire regions of Africa. It also led to ethnic conflicts and exacerbated gender inequalities in affected communities.

Economic consequences for Europe

The wealth accumulated through slavery supported the Industrial Revolution and Europe’s development. European banks and industries built their prosperity on the trade of human beings.

Resilience and afro-descendant culture in America

Despite oppression, slaves managed to preserve their cultural traditions. The Afro-descendant diaspora developed unique identities and cultures, merging African heritage with local influences.

Conclusion

Today, memorial initiatives and historical reflections allow for a better understanding of this dark period in history. This understanding is essential to remember past atrocities and work towards building a more equitable future, respectful of the dignity and heritage of African and Afro-descendant peoples.