Over the centuries, the island we now know as “Martinique” has borne at least three different names: Jouanacaera, Madinina/Madiana, and Martinica. These successive names—Amerindian, mythological, and European—reflect the encounters between the island’s first peoples, Caribbean legends, and European expansion. More than a simple etymology, “Martinique” represents a layered history and a deeply rooted Caribbean identity.

Before the arrival of Europeans, the Kalinagos (or “Caribs”) referred to the present-day Martinique as Jouanacaera (or Ioüanacéra / Wanakaéra, depending on transcription).

This term is made up of two elements from the Carib language:

- ioüana = iguana

- caéra = island

Thus, Jouanacaera literally means “the island of iguanas.” This name, based on direct observation of the local fauna, illustrates the intimate relationship between the island’s first inhabitants and their environment. The iguana, a common presence in forests and mangroves, played a key role in Amerindian diet and symbolism: it embodied resistance to the tropical climate and the ability to blend into hostile environments.

At the same time, the Taínos of Hispaniola spoke of a mythical island named Mantinino, said to be inhabited solely by warrior women—akin to Amazons. This legendary name inspired the naming of several islands in the Antillean arc, including Martinique. The name’s transcription evolved over time:

- Mantinino → Madiana / Madinina → “Island of Women”

- Through popular assimilation and distortion, Madinina became Madinina.

A poetic interpretation links Madinina to “the island of flowers,” owing to the lush and multicolored vegetation that dazzled the island’s first European visitors. Whether born of tales of Amazons or the island’s floral splendor, this version casts Martinique as a space both mythical and sensual—where nature and legend converge.

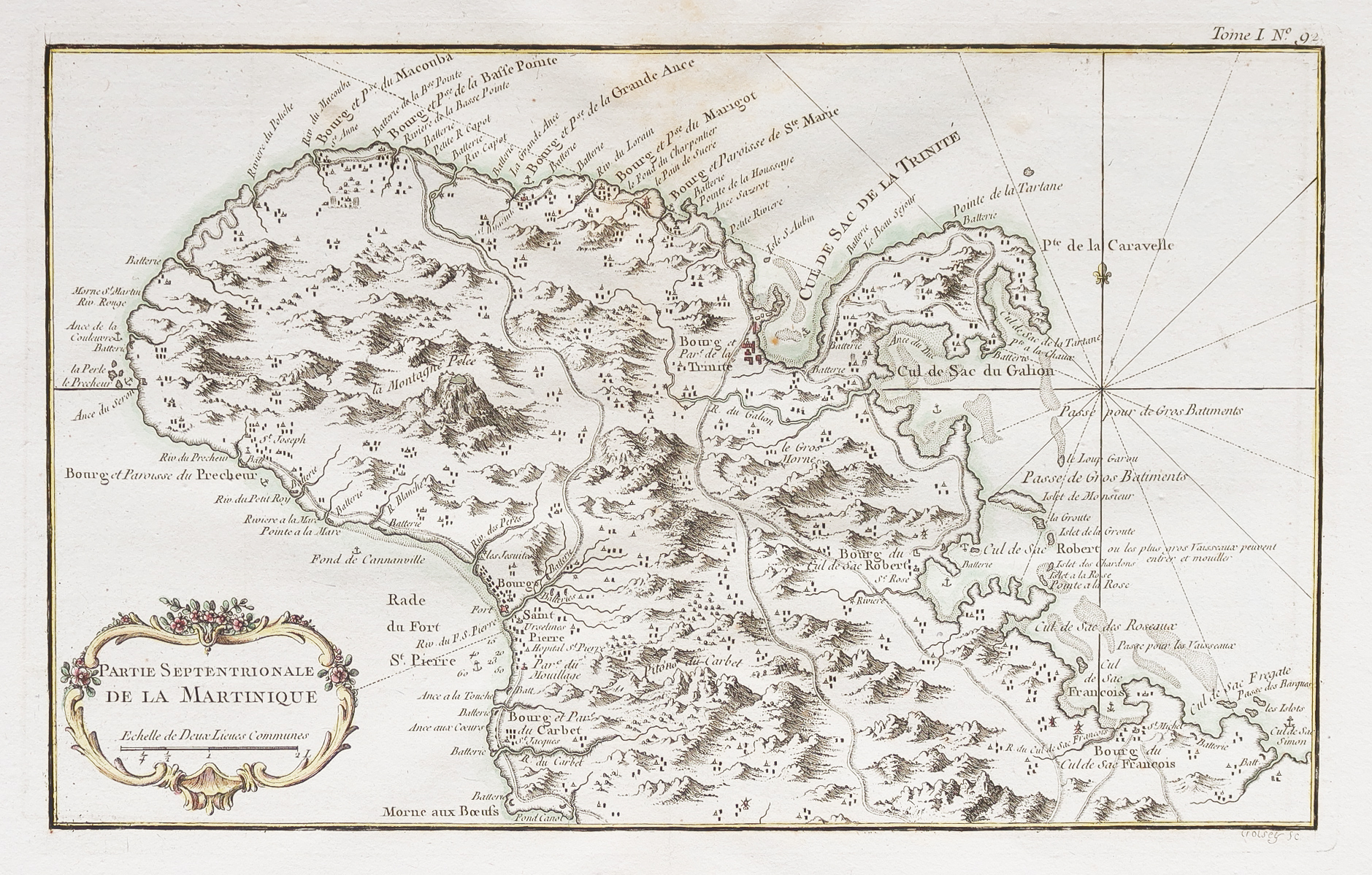

On June 15, 1502, during his fourth and final voyage, Christopher Columbus actually landed on the island’s shores. He had already sighted it on November 11, 1493—the feast day of Saint Martin (bishop of Tours, traditionally honored that day). In memory of this calendrical coincidence, he named it Martinica or Martinino.

This gives rise to the third origin of the modern name:

- Martinica / Martinino → Martinique (Frenchified form, by analogy with neighboring Dominica).

Columbus wasn’t the first European to “discover” the island, but he was the one to officially fix its name in the records of the Spanish Crown—before it gradually came under French control starting in 1635.

The coexistence of these three names—Jouanacaera, Madinina, and Martinica—resulted in a complex toponymic evolution:

- Amerindian (Jouanacaera) → recognition of geographic reality

- Mythical/legendary (Madinina/Mantinino) → symbolic and spiritual significance

- European (Martinica) → integration into Christian and imperial imaginaries

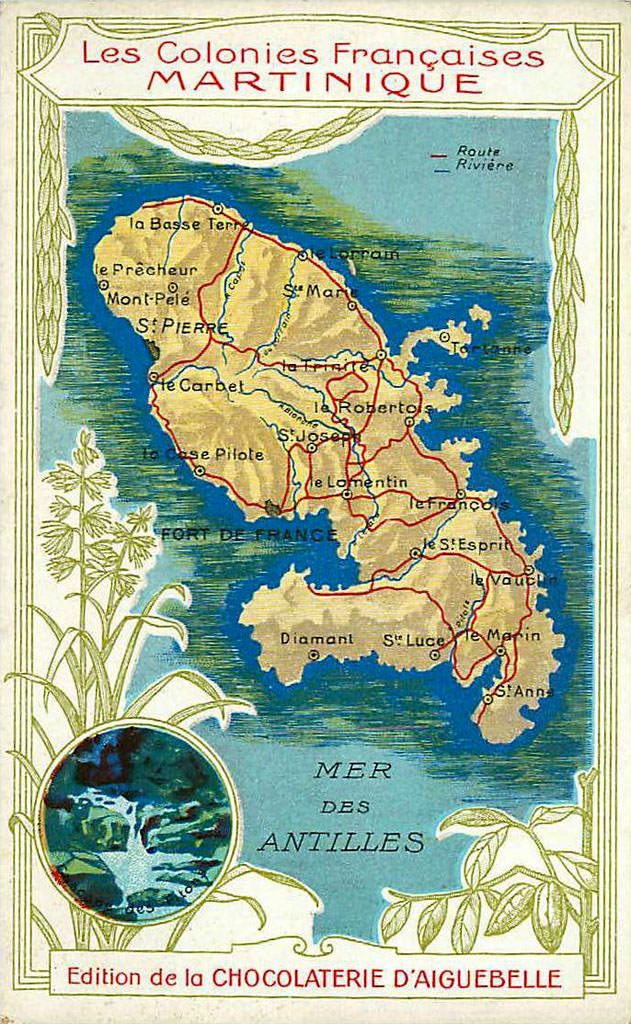

In the 17th century, French colonists—guided by Spanish maps and Taino-Carib phonetics—adopted Martinique. Already common among sailors, the name took hold quickly:

- It evoked the feast of Saint Martin, a prominent figure in Catholicism

- It clearly distinguished the island from nearby Dominica (“Marie-Therese Island”), avoiding confusion

- It preserved an echo of Amerindian names through the “-inique” sound, reminiscent of Madinina

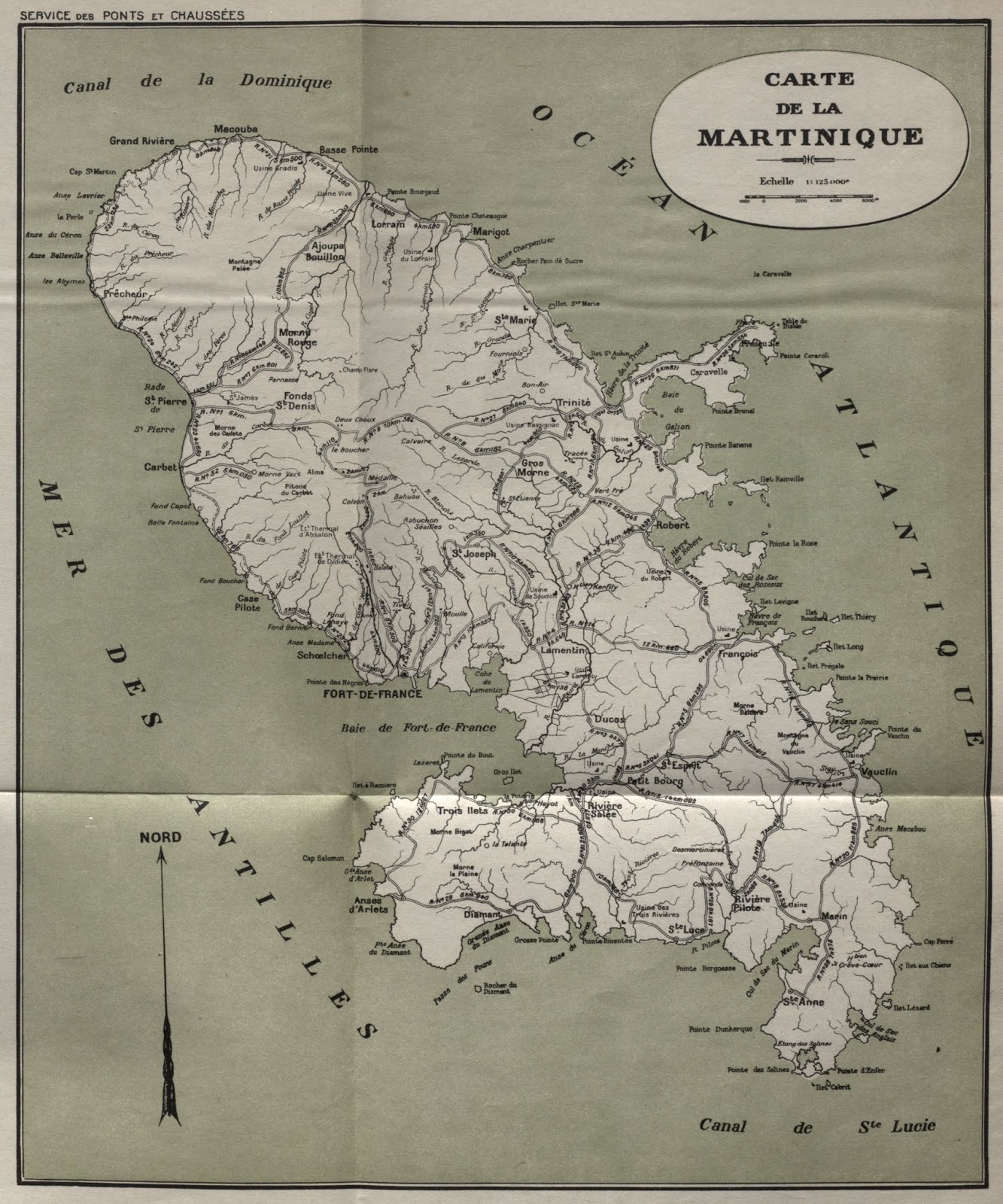

On 17th–18th century nautical charts, Martinique became the stable name, as older forms gradually faded.

Meanwhile, a Martiniquan Creole developed, drawing on the Carib language, French, and West African tongues:

- Matinik or Matnik are common Creole forms, retaining the root “Mati(n)-” and a toponymic suffix similar to the Amerindian original.

This Creole name underlines cultural continuity: even after colonization, Taino and Kalinago memory survives in the language.

Today, Martinique’s single territorial collectivity officially recognizes Matinik as one of the island’s names, visible on many road signs and tourist materials.

Martinique today:

- A single territorial collectivity of the French Republic (replacing both region and department statuses)

- An outermost region of the European Union

- An associate member of CARICOM, OECS, ACS, and ECLAC

- A UNESCO biosphere reserve (land and marine) since 2021

- A UNESCO World Heritage Site (Mount Pelée and the Northern Pitons) since 2023

Its population of 361,019 (INSEE, 2022) speaks both French and Creole, living within a cultural blend that brings together Amerindian, African, and European heritage.

Sources

- Armand Nicolas, Histoire de la Martinique, Tome 1: des origines à 1848, Ed. L’Harmattan, 1996

- Alfred Métraux, La langue des Caraïbes insulaires, Journal de la Société des Américanistes, 1938

- Jean-Luc Bonniol, La couleur comme maléfice: colonialisme et identités culturelles dans la Caraïbe, Albin Michel, 1992

- Claude Lévi-Strauss, Race et Histoire, UNESCO, 1952