Through this article, Nofi dives into the incredible, almost unbelievable, story of a man who led his country into a spiral of terror and madness. A man who governed one of the most brutal regimes in 20th-century Africa, using the most ruthless methods to maintain his power. This man is Francisco Macías Nguema, the “mad dictator” of Equatorial Guinea.

Francisco Macías Nguema: The rise of a dictator

Our story begins in 1924 in a small village in Equatorial Guinea, then a Spanish colony. Francisco Macías Nguema was born into a modest family in a society still marked by the harshness of colonial rule. From an early age, he displayed intelligence but also a peculiar temperament, a desire for power, authority, and a deep distrust of those around him. He pursued his studies, eventually becoming a civil servant in the colonial administration, quickly making a name for himself. His methods were brutal, sometimes devious, but effective.

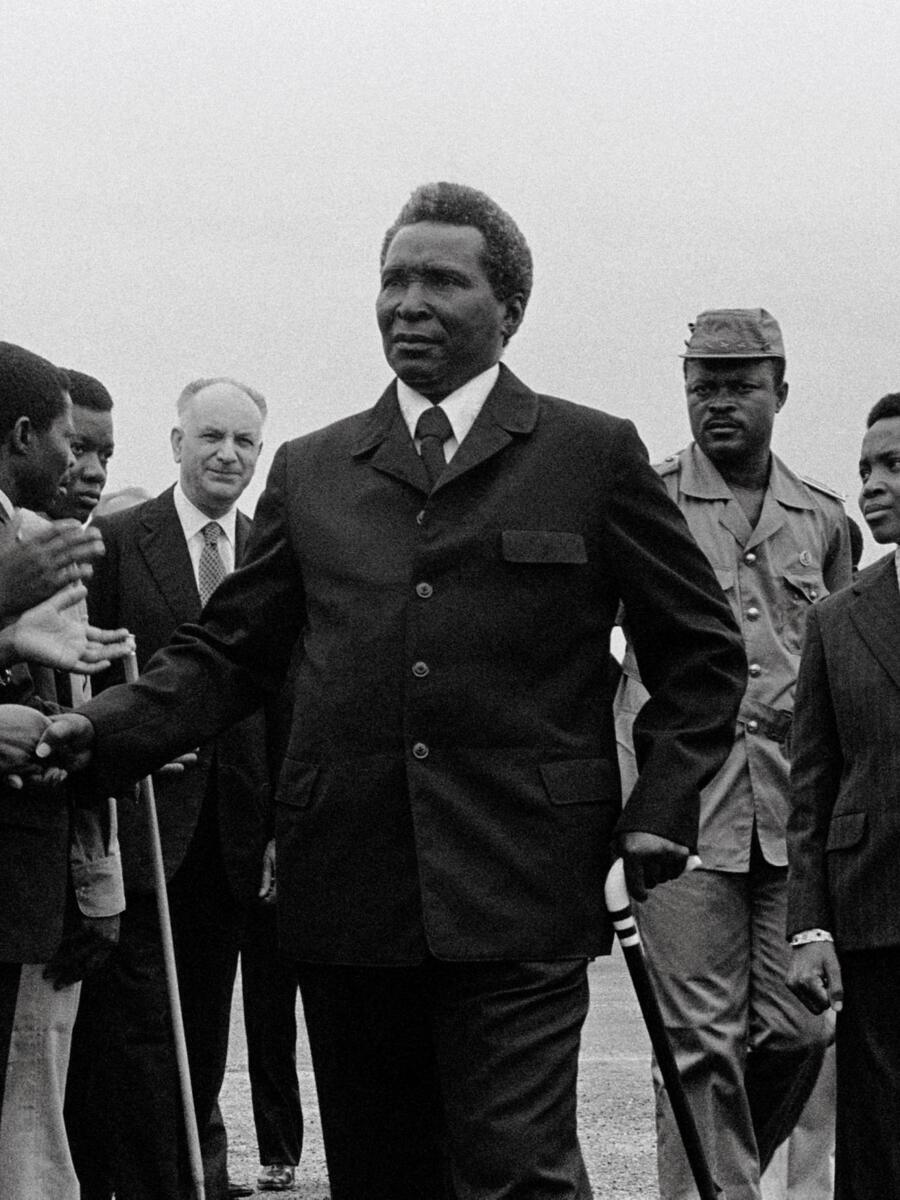

In 1968, Equatorial Guinea was on the brink of independence, and Nguema, with his charisma, emerged as a key political figure. In the first presidential election, he ran a fervent, nationalist campaign. With an anti-colonial rhetoric filled with hatred against Spanish colonizers, he promised the people a future where Equatorial Guinea would be free and prosperous. His promises resonated with the people, who saw him as a symbol of resistance against the oppressor.

However, what was expected to be a fair election soon turned sinister. Nguema eliminated potential rivals. His primary opponent, Bonifacio Ondó Edu, was accused of conspiracy—an accusation fabricated by Nguema but one that justified Edu’s arrest. Ondó Edu mysteriously disappeared, without investigation. With his main rival gone, Nguema easily won the election, becoming Equatorial Guinea’s first president.

But what should have marked the dawn of a new era for the young country quickly turned into a nightmare. Nguema soon revealed his true nature. Instead of delivering freedom and prosperity, his rule transformed into a terrifying dictatorship.

Just months into his presidency, Nguema established an unprecedented repressive system. Critical voices, political opponents, intellectuals—anyone who might question his authority—were systematically eliminated. He created a secret police force, the Jóvenes Antiguos de Macías (JAM), composed of youths trained to obey without question. This militia became the armed branch of his repression, infiltrating neighborhoods and villages, surveilling and reporting on any suspicious behavior.

Nguema assumed grandiose titles, declaring himself “President for Life,” “Supreme Leader,” and even “Unique Miracle,” as if seeing himself as a divine being sent to rule his people. His speeches grew increasingly erratic, and his paranoia deepened. Obsessed with imaginary plots, he saw enemies everywhere.

Nguema’s madness drove him to decisions that plunged Equatorial Guinea into economic chaos. Convinced that intellectuals and cultural elites posed a threat, he sought to eliminate them. Schools closed, teachers were imprisoned or executed, and books were burned. He accused doctors of spreading “anti-patriotic” ideas, forcing most to flee the country, leaving just two doctors to serve the entire nation, resulting in a disastrous health crisis.

He ordered the expropriation of foreign companies, particularly Spanish-owned ones. Their assets were seized and handed over to Nguema’s family and allies, who lacked the skills to manage them. The country’s once-thriving cocoa plantations were abandoned, and Equatorial Guinea, which had once exported this valuable resource, was now struggling to feed itself. Famine took hold, but Nguema was indifferent.

Nguema’s appetite for the absurd culminated in 1969 with the infamous Christmas massacre. At Malabo’s stadium, 150 political prisoners were brought before a terrified crowd. Soldiers from the JAM, dressed as Santa Claus, opened fire, killing all deemed “enemies of the nation.” This public massacre sent a clear message: no one was safe, and any opposition would be crushed in blood.

Nguema’s paranoia reached disturbing extremes. He closed the capital to everyone outside his inner circle, surrounded himself with guards and occult relics, and believed that he could absorb his enemies’ power through their skulls and remains. His residence filled with these macabre “trophies,” symbolizing his descent into superstition and delusion.

The terror continued. Ethnic minorities were persecuted, entire villages razed, and tribes like the Pagalos and Bobis saw their populations decimated. Even children between ages seven and fourteen were forced to undergo military training, holding wooden guns under the threat of punishment for disobedience.

In the final days of his rule, Nguema no longer trusted anyone. Isolated in his residence at Mongomo, he conducted dark rituals in a desperate bid to maintain his power. Meanwhile, his nephew, Teodoro Obiang, was preparing a coup.

On August 3, 1979, after days on the run, Francisco Macías Nguema was captured in the jungle. Detained, he faced trial for genocide, embezzlement, and atrocities against his people. The verdict was swift: he was sentenced to death. However, no Equatoguinean soldier wanted to execute him, fearing a posthumous curse. In the end, Moroccan mercenaries were called to end the reign of terror that had gripped Equatorial Guinea for eleven years.

On September 29, 1979, Francisco Macías Nguema was executed, ending an eleven-year reign of terror.

References

- Ndongo-Bidyogo, Donato. Historia y tragedia de Guinea Ecuatorial. Ediciones Akal, 1985.

- Liniger-Goumaz, Max. Small is Not Always Beautiful: The Story of Equatorial Guinea. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers, 1989.

- Ávila Laurel, Juan Tomás. The Gurugu Pledge. And Other Stories Publishing, 2014.

- Liniger-Goumaz, Max. Guinea Ecuatorial: Los Derechos Humanos, « de Hecho ». Editions L’Harmattan, 1993.

- Meisler, Stanley. United Nations: The First Fifty Years. Atlantic Monthly Press, 1997.

- Rey, Claudine. Les républiques d’Afrique noire et le pouvoir militaire. Presses Universitaires de France, 1981.

- Africa Watch Committee. Guinea Equatorial: A Promise Betrayed. Yale University Press, 1991.

- Le Vine, Victor T. Politics in Francophone Africa. Lynne Rienner Publishers, 2004.

- Ramos, Agustín. Equatorial Guinea, the Forgotten Dictatorship. California State University, 1998.

- Nwoji, Ike. Reflections on West Africa’s Disturbing Issues. AuthorHouse, 2012.