Km (black) and dšr (red) were also used in ancient Egypt to distinguish one individual from another.

‘Black’ and ‘red’ in Ancient Egyptian from a microsocial perspective

In a previous paper, I have mentioned the opposition between “red” and “black” people at the scale of populations, that is to say from a macro-social perspective.

This kind of opposition is often used nowadays. As noted by Diakonoff (1981) quoting his colleague Porkhomosky, red is often used by Africans south of the Sahara to refer to ‘nomadic people’ (e.g. Tuaregs, Fulani).

As pointed out by Solange Ashby, the same distinction is used by modern-day lighter-skinned Amhara who described themselves as ‘red’ but call Nara, Sidama and Oromo ‘black’. She adds that the same distinction may have been used by Ancient northern Ethiopians, the Aksumites, who distinguished between the Red and Black Noba.

An opposition between “red” and “black” was also noted in ancient Egypt to distinguish one individual from another, that is from a micro-social perspective.

It was particularly used to distinguish individuals with the same name. For example, two Ancient Egyptian brothers were both nicknamed ḥpj Hapi.

Schenkel (1963) : Black vs Red-haired?

While one was nicknamed ḥpj km, the other was ḥpj dšr. Schenkel (1963) has suggested that this was a distinction made between the hair color of the people so named. ḥpj km would have had black or brown hair and ḥpj dšr blonde (sic) hair.

Lam (1993): Dark vs Light-skinned?

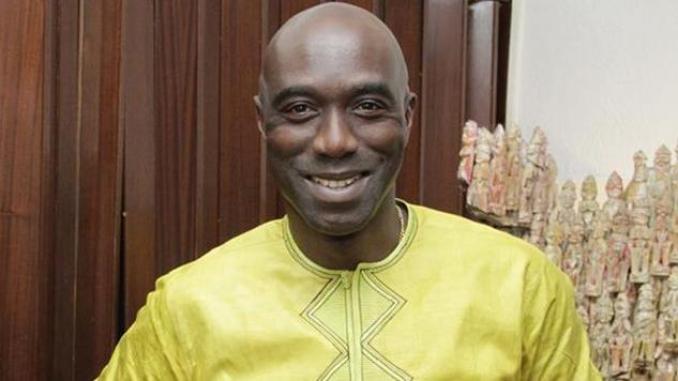

One cannot reject this hypothesis a priori. However, an alternative hypothesis has been suggested by Lam (1993: 259-264), according to which the epithets dšr and km were references to the skin color of the people so named. When a person is described as km, this person was considered as dark-skinned. When described as dšr, he was fair-skinned. Lam recalled that this type of distinction was common in ‘Black African’ languages, wondering even if it was not exclusive to them.

The example of the Fon language

Let’s illustrate Lam’s hypothesis with the Fon language, mainly spoken in the Republic of Benin. To refer to a dark-skinned Black human being, a dark-skinned ‘Black’ man or woman, one will say respectively mɛ-wi (literally human being-be black), nya-wi (man-be black) and na-wi (lady-be black).

On the other hand, to designate a ‘black’ human being, a ‘black’ man or a ‘black’ woman with light skin, one will say respectively mɛ-vɔ (literally human being-red), nya-vɔ (man-red being) and na-vɔ (lady -be red).

Issues with the Schenkel (1963) hypothesis

However, Lam does not mention the Schenkel hypothesis and therefore does not refute it. One argument, in my opinion, supports the hypothesis of the first. There are Egyptian personal names simply consisting of a (nominalized) colored adjective like km ‘the black’, kmt ‘the black’ (Ranke 1935: II, 79) dšr ‘the red’ (Ranke 1935: II, 180 ). There is also a personal name dšr-šnj literally meaning ‘hair (is) red’, red head ’(Ranke 1935: II, 180).

On the other hand, there is no km-šnj, the black color of the hair having clearly been the color of the great majority of the Egyptian population as attested by a spelling of the word km ‘black’, the determinative of which is a strand of black hair. The mention of dšr-šnj where the color is on the hair seems to suggest a distinction with the names of people using only one color, such as km ‘the black’, kmt ‘the black’, dšr ‘the red’.

Can we conclude from this that they relate to the skin color of the individuals so named?

The fact that no part of the body is specified suggests that the color relates to the entire individual. That individuals are named km “black” and kmt “black” when the vast majority of Egyptians must have had black hair suggests that this would hardly be a reference to hair color.

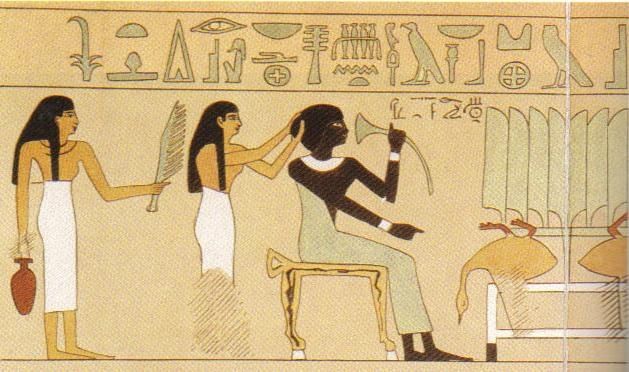

As we have seen, the skin of the Egyptians could be qualified as km to refer to a darker complexion than another, in this case that of the harvesters with the skin darkened by the sun compared to other people whose skin was not. The term km also appears, for example, as a verbal predicate in the name of Kemsit kmst “the woman is black”, a wife of King Mentuhotep II.

Depictions of her make no doubt that her name refers to her very dark skin color. This should also be the case for the names mentioned above where the color refers to the whole individual (whether mentioned or not) such as km ‘the black’, kmt ‘the black’, dšr ‘the red’ rather than on only one part of the body like dšr-šnj.

The range of the color words km and dšr in Ancient Egyptian

Does this allow one to conclude that the term dšr, when applied to human beings, refers to lighter-skinned people as Lam posits?

As Lefebvre (1949) explains, the term could be used to describe things ranging from what we would describe as tawny ’, yellow’ and red ’. Referring to the desert regions around Egypt, called as we have seen dšr.t, Lefebvre (1949) explains that it is “unlikely that the desert appeared as exclusively red to the Egyptians: in fact, on a wooden stele from the Cairo Museum, originally from the Theban necropolis, the Gebel is painted in striped yellow and speckled with red; we would say that it is ‘fawn’. Dšr is also the color of barley used to brew beer, it dšr, which we would consider “blonde”. “

We have seen that the red-brown (or darker) color of Egyptian harvesters working in the sun was rendered by km. However, the rest of the variations going from red to yellow, including fawn, were referred to as dšr. However, in the stereotypical depictions of the ancient Egyptians, women are represented as having skin ranging from white to yellow.

We can therefore think that the skin of women was described as dšr, just as the complexions ranging from yellow to red must have been. It is therefore legitimate to that the words km and dšr, when used as complements of people’s names, referred to their dark and lighter complexions, respectively.

The white color of the skin of some women in Egyptian art does not at first glance fall within the spectrum of colors covered by dšr. However, it will be noted that there is no name of a person using the expected term for ‘white’ ḥḏ, nor other Egyptian colors to refer to the person or part of the body, as there is for km and dšr. But why not have used ḥḏ to denote a very white skin tone? Was that white complexion realistic?

The solution seems to be to see in km and dšr opposed by the absence and the presence of light. This is what Goebs (2008) suggested. She refers in particular to texts from the Book of the Dead and Coffin texts. In the second (CT 577 (VI, 192d) 4), the deceased is described as nb dšrw, the ‘master / possessor of the redness’ and describes his opponent in the afterlife as ‘dark (km)’ behind him in court (jw = f / hm r = jm ḏ3ḏ3t).

In this case, Goebs (2008: 161) explains that:

“Here the relative lack of luminosity and visibility of the opponent seems to underlie the triumph of the deceased, who overpowers him by being brighter and thus more visible, that is, more” effective “3ḫ) than him. ”

In chapter 179 of the first, Goebs reports that the transfer of the Great Red (dšrt ʿ3t) and her knowledge of the butchery led the deceased to be victorious against his enemy, again described as “‘dark’ (km) behind him in court ”(jw = f km hr = jm ḏ3ḏ3t).

As in the case of humans at the microsocial scale, black emerges as a standard from which red stands out with its greater degree of luminosity and clarity. Contrary to what these last examples may suggest, the positive connotation is much more often associated with black (km) than with red (dšr) in Ancient Egyptian.

All of these accounts are limited to the period from the Old Kingdom to the New Kingdom. During this time, anger is expressed through an expression including the word dšr. It’s about dšr jb, which literally means rouge heart is red ’.

As Lefebvre (1954) notes, it was not until the period known as the Late Period that the same idea was conveyed by the expression dšr ḥr ‘red face’, while the reverse is expressed by the expression ḥḏ ḥr ‘white face’, that is to say ‘benevolent, generous’.

Is this a reflection of a time when the ancient Egyptians had a fairer skin color and nervousness resulted in visible reddening of the skin? The question is worth asking, even though dšrw, a derivative of dšr ‘red’ by itself means ‘anger’ and as we have seen, the heart, a naturally red organ, is referred to as dšr to refer to to anger.